What Percentage of Public Pension Income is From Investment Returns? Or Contributions?

by meep

Here is something I’ve heard often:

I think investment income covering 80% of the cost is aspirational. In reality it hasn’t been working out that way, which is why contribution rates have gone up in most places. https://t.co/AuyvCynpyu

— Mary Williams Walsh (@marywalshnyt) October 13, 2018

What percentage is it really?

The problem is, the data I have go back to only fiscal year 2001. That said, current benefits paid outweigh earlier years, so perhaps 16-17 years of data can tell us what percentage of “income” for these funds are from investment returns, and how much from contributions.

PUBLIC PENSIONS DATABASE: INVESTMENT INCOME AND CONTRIBUTIONS

We’re going to look at total contributions (employer and employee), and investment income as the actual cash flow income. At this point, these are the only components I will use, and then I will address one component I did not include.

I did this calculation for each plan in the Public Pension Database, and I also noted how many years of data I had.

Here is the distribution of percentage of income from contributions:

Now, is that near 20%? Looks to me around 40% of the income being from contributions is the most frequent percentage, and extremely few are at 20%.

Okay, maybe I’m not entirely fair… because I’m not including unrealized capital gains (or losses).

INCLUDING GAINS AND LOSSES

Unrealized capital gains/losses has to be included, to be a bit fairer. I have to get at this indirectly — it’s not a cash flow, and the assets aren’t merely growing .. there are bits going out due to benefits and expenses being paid.

So we will look at the total unrealized capital gains/losses as: Assets at end + (sum of all cash outflows) – (sum of all cash inflows) – Assets at beginning. This is the gain/loss in assets not explained by cash flows, thus it is unrealized.

I will use market value of assets for the begin and end.

Here’s how the proportions break out:

Isn’t that interesting? As in, almost exactly the same as the prior histogram?

It also gave me an indication that unrealized gains/losses were already included in the net income (okay, income statements are different from statements of cash flows. I should have remembered that.) For almost all plans, this calculated amount was zero.

You can get the spreadsheet with my calculations here.

WHAT DOES THIS 40% MEAN?

Let us think through what I just showed… for current cash flows. I didn’t look at benefits going out at all, except to correct for unrealized gains/losses that I thought may have been missed in the income statement (it was for a few funds, fwiw).

I’m showing how much contributions are coming in as a percentage of all the net inflows, including investment income. I was including both employer and employee contributions.

These contributions, for theoretically well-managed pensions, would be for current service and thus future pension benefits.

Current benefits are being paid out, again in our theoretically well-managed pension, based on investment income from assets built up from contributions of long, long ago.

That’s the theory, at any rate.

When I worked for a mutual life insurer, we made clear to trace a dollar deposit over the decades, with the depositor getting appropriately credited for their account over time. At retirement, we could give a full accounting for that purpose – how much had been deposited, and how much was dividends accumulated over the decades.

I can’t do that with public pension funds.

And I especially can’t do that when current contributions are going in to cover decades-worth of undercontributions.

REAL DATA: CHECKING ON CALPERS

So I found a specific claim from Calpers:

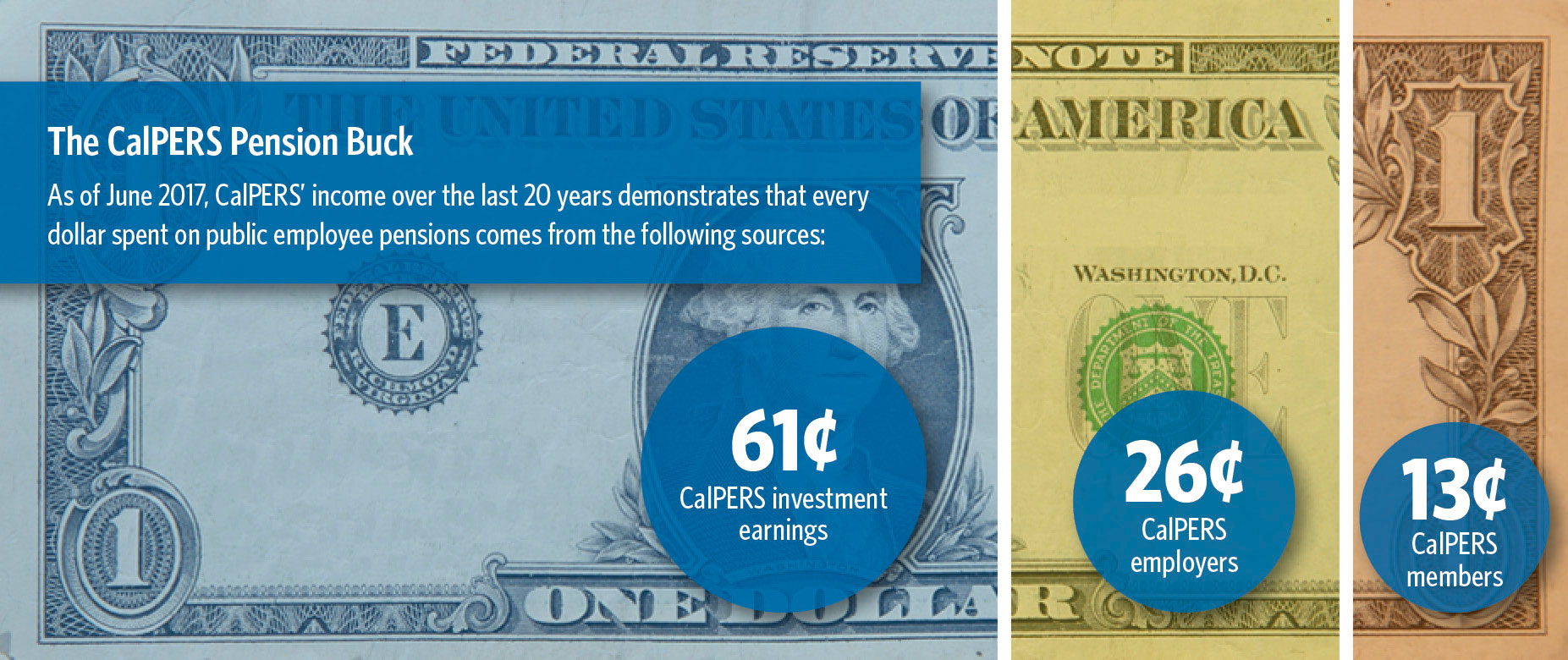

The CalPERS Pension Buck illustrates the sources of income that fund public employee pensions. Based on data over the past 20 years ending June 30, 2017, for every dollar CalPERS pays in pensions, 61 cents comes from investment earnings, 26 cents from employer contributions, and 13 cents from employee contributions. In other words, 74 cents out of every public employee pension dollar is funded by CalPERS’ own investment earnings and member contributions.

Hey, that actually accords with what I said: about 40% from contributions. I just so happened to lump in employer and employee contributions.

So this makes some sense – let me just look at percentage from employer contributions alone and see what happens:

Hmm, it looks a bit better, to the extent that employees are picking up the necessary contributions.

Oh, and what number did I get for the employer percentage for Calpers? 29%. For my 16-year weighted average, compared to Calpers’ 20-year weighted average, I would say those are very close. I happen to agree with their calculation as to what it is.

I may differ with respect to what this really means.

WHAT SHOULD THE PERCENTAGE BE?

The percentage provided by contributions versus investments is dependent on the “shape” of the pension participant population.

One would hope that as the population “ages”, that is, there are more retirees compared to active participants, that more and more would be coming from investments.

After all, in a closed block of annuities, all of the income to pay off the annuities have to come from investments and drawing down assets. No more contributions coming in. What’s true of retirement annuities is similarly true of pensions.

So there’s no one perfect percentage the mix should be. It’s demographically dependent as to what the mix of contributions-to-investment returns it should be.

The issue for Calpers is that its contribution amounts as a percentage of active payroll is precipitously climbing, for a variety of reasons. It’s very difficult to reason the taxpayers into not noticing how much the costs are climbing:

As pension costs go up, California cities turn to voters for tax increases

On November 6, more than 100 California and counties are asking voters to increase sales, hotel and other taxes to bolster their general fund budgets.

The local governments in many cases say the new revenues are needed to pay for city services such as public safety, roads and other general services. But the tax increases also come at a time when they’re facing increasing pension costs that are contributing significantly to budget shortfalls.

….

One of the biggest cost increases the city [of Santa Ana] is facing is for pension contributions which are anticipated to go up an average of 13.7% a year from $45.1 million in 2017-2018 to $81.2 million by 2022-2023, according to a February report to the City Council.Santa Ana’s contributions to the California Public Employees’ Retirement System made up 14% of its budget, the report said.

…..

A January 2018 League of California Cities report predicted that cities that are part of CalPERS will see dramatic increases over the next seven years, possibly to unsustainable levels.

So, that 60% of pension fund income is currently coming from investments doesn’t help the issue of how much more is going to come from employer (and employee) contributions in the future — much of which will be to cover the old pension costs of people already retired.

That’s part of an increase that has been happening over a decade. In 2006-2007, the average city spent 8.3% of its general fund budget on CalPERS costs, the report said. That average rose to 11.2% in 2017-2018 and is expected to go to 15.8% in 2024-2025, according to the league.

By keeping this to percentages, you may ignore the actual relative increase.

8.3% of budget -> 11.2% of budget, assuming all else stays the same, means a 35% increase in pension costs. If the city budgets were also growing at the time, the growth is far more than that. But let’s just assume a 35% increase in cost from FY2007 – FY2018. 35% increase over 11 years… not too bad, right?

But let’s look at the next bit. 11.2% of budget to 15.8% of budget — that’s a 40% increase. From FY2018 – FY2025. Only 7 years.

That’s not looking too sustainable.