Visualizations of Public Pension Fundedness and Why Fundedness is Decreasing

by meep

I saw that the Public Plans Database folks had a new paper out:

The update’s key findings are:

The funded ratio of state and local pensions edged up to 73 percent in FY 2018, but has been largely flat for several years and is well below its peak in 2001.

Liability growth has steadily declined during the past two decades – from 7.7 percent in 2002 to 3.8 percent in 2018 – but asset growth has been even slower.

Given these trends, if plan sponsors want to improve plan funded ratios, a key challenge is to increase their asset base through contributions.

One way forward is to adopt more stringent funding methods such as level-dollar amortization and shorter amortization periods.

Another, more important, change is to lower assumed investment returns, which would help ensure funding progress by further raising required contributions.

I highlighted two points I think particularly important.

The full piece is here, and I’m going to take a few of their graphs and redo them.

DISTRIBUTION OF FUNDEDNESS

Here is their histogram of fundedness ratios for the plans in their database:

Now, I have a lot of problems with this distribution, not the least the method in which they cluster the plans. (I will do something different.)

But let’s start with the simple stuff first. Let me redo the distribution. I grabbed the data from here: Public Plans Database Interactive Data, and grabbed FY2018 numbers, and got the funded ratio for each plan. I filtered out any plans missing data.

I made a histogram based on their data, but they claim to have data from 190 plans… and I had only 179 (after deleting the ones missing FY2018 data). The full set is of 190 plans… but I had blanks for funding ratios for many of them.

Okay, here is the plain histogram. I don’t exactly match theirs, but they may have used the FY2017 numbers for those who didn’t have the FY2018 ones available. In any case, they’re close:

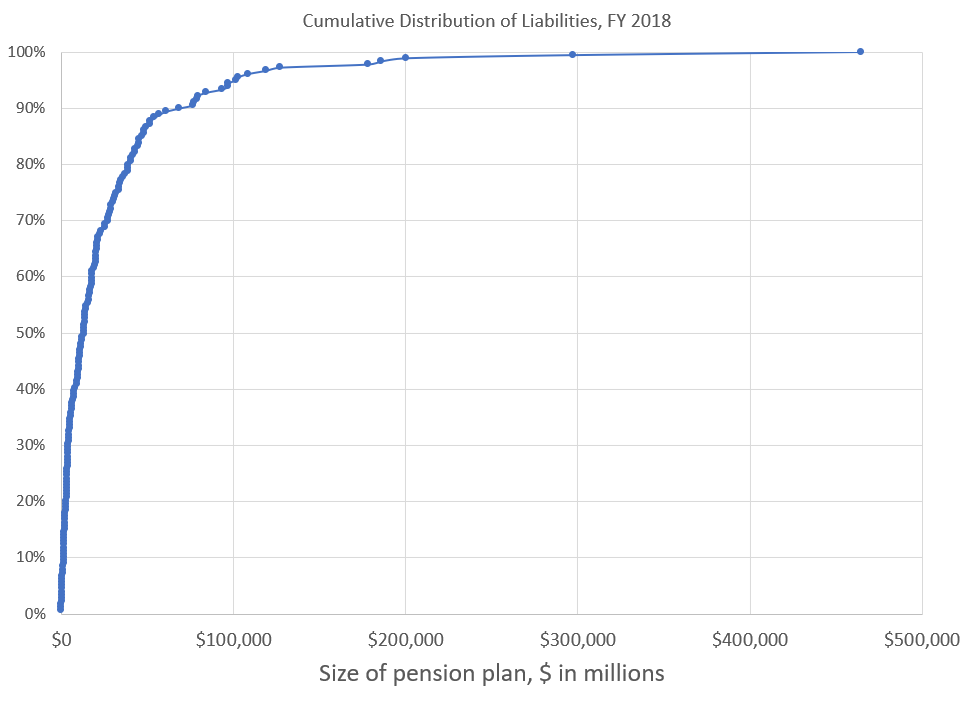

But I don’t like weighting the pension plans by count — some, like Calpers, are much, much larger, and really should count for more. Let’s take a look at the distribution of insurers by liability size — but because of how these scale, I’m going to do this as a cumulative distribution graph:

Part of this is due to how the Public Pensions Database has been constructed: they prioritized doing the largest funds first, and then went to smaller plans. A bunch of plans will never get in the database, as long as it’s a manual process. The largest plan, unsurprisingly, is Calpers. The median plan size is $13 billion in liabilities. You can see that Calpers is about $465 billion. That’s a lot bigger, eh? (These are total liabilities, not unfunded liabilities)

Let’s weight the histogram by liability and see what happens. Let’s compare against the per count histogram:

You can see that where Calpers (and the other large pension plans) fall help “boost” that middle area.

EVOLUTION OF FUNDED RATIOS

This next graph, I am not fond of:

I don’t want to replicate that one at all. I want to look at percentiles themselves evolving — again, weighted by liability size. What’s the median funded ratio? 25th percentile? 75th percentile? Maybe put in a 10th percentile & 90th percentile. Now, in general, the pension plans maintain their relative rank ordering from year to year, so you will often get things matching up in the same group each year.

Let me do these percentiles by count first, because that is very easy to calculate:

Isn’t that interesting? All of the percentiles I’m tracking have about the same trajectory — the spacing is about the same each year (about 10 percentage points, though it ranges from 7 percentage points up to 13 percentage points).

The 90th percentile decreased 27 percentage points from FY 2001 to FY 2018 (120% to 93%), the median (50th percentile) decreased 25 percentage points (99% to 73%), and the 10th percentile decreased 24 percentage points (78% to 54%).

Now, the following is more complicated to compute, but I still can do it. Here’s the same percentile graph, but weighted by liability now:

Now, this one isn’t quite so smooth, which I find interesting. While the first graph show all the percentiles decreasing about 25 percentage points from 2001 to 2018, the second graph shows about a 30 percentage point drop.

In general, I do like looking at the public pension database statistics weighted by liability size, because I think the largest pensions do have more of an effect on policy compared to small plans. Why should Calpers ($465 billion) count just as much as Des Moines Water Works ($61 million)?

The overall results do tend to be similar, but I know that only after having done the calculations and comparisons.

CONCLUDING THOUGHTS

A few things to think about:

On July 1, 2001, the S&P 500 was at 1,204.45. On July 1, 2018, it was at 2,793.64. That is a cumulative increase of 132%.

Funded ratios for pension plans fell around 30 percentage points in their funded ratios, going from fully-funded in most cases to only about 70% funded.

Why is that?

Some background reading:

Public Pensions: Why Do 100% Required Contribution Payers Have Decreasing Fundedness?

Public Pensions Practice: Where are the Screaming Actuaries?

On Full Public Pension Funding: A Follow-Up

Specific pension plans have weathered the roiling market movements well, but it is very few of them. The plans that supposedly are doing what they’re supposed to be doing… their funded ratios are falling, too. Even in a rising market.

Notice that I didn’t say what the S&P average annual return was from July 1, 2001 to July 1, 2018. It was 5.1% per year. Yes, this is a geometric time-weighted average.

In 2018, there were only 3 plans that have assumed return on assets that low: Pennsylvania Municipal (5.25%), Charleston, WV Firemen’s Pension (4.5%), and Little Rock Firemen’s Fund (5%). Most plans have assumed returns much higher — like at 7.5%.

7.5% compounded over 17 years is almost 50% higher than 5.1% compounded over 17 years.

That may give you an idea what’s going on.

Finally, a motto from Jeremy Gold (RIP):

Good policies cannot be based on bad numbers.

The numbers above are bad, for a variety of reasons. They do indicate a system-wide problem.

Related Posts

Kentucky Pensions Even Closer to the Brink: New Assumptions, New Report

Public Pension Roundup: Bailing out Pensions, The Return of Pension Envy, Kentucky Lawsuit, and more

Kentucky Update: Republicans Take Legislature, Pensions Still Suck, Hedge Funds to Exit