Motor Vehicle Accident Deaths: High-Level Trends, 1968-2020, Part 1

by meep

I am splitting up my posts on Motor Vehicle Accident Deaths into three parts, because I want you to make a guess about some of the patterns ahead of time, because I think you will be surprised about what you will see.

If you see this in a timely manner, please vote in my twitter polls:

Try two on the poll

— Mary Pat Campbell (@meepbobeep) March 1, 2022

Which age group in USA had highest death rate from motor vehicle accidents (not adjusted for miles driven/traveled) in 2019?

Which age group in USA had highest death rate from motor vehicle accidents (not adjusted for miles driven/traveled) in 2020?

— Mary Pat Campbell (@meepbobeep) March 1, 2022

I know this may not embed too well, and you may need to click through to twitter to vote (and you probably need a twitter account to vote). I will share final results in the next post.

Note: there are two polls, one about 2019, and one about 2020.

Also note: I mentioned that these rates are just plain death rates — number of deaths per 100K people per year, without any adjustment based on number of miles traveled. We will see in this post today why that is an important consideration, because how much people drive usually has a big effect on motor vehicle accident deaths.

High-level trends of crude rates and age-adjusted death rates for motor vehicle accident deaths

Here is our standard graph:

I will note that the crude rate and age-adjusted rate (which uses a year 2000 standardized population) give us, essentially, the same result for most of the period of 1968-2020.

It’s an interesting downhill ride for most of the graph, with a few precipitous drops.

Would you like to know why there were a few very steep drops? It’s very simple.

When people drive less, there usually are fewer accidents

To make it simple, I’ve graphed (approximately) the recessions in grey, and also marked off the early 1970s oil embargo.

That is quite the slide in death rates over a two-year period.

In general, the more people drive, the more chances they have to get into car accidents. It just makes sense. People drove less when there was less (and much more expensive) gas.

Except in 2020.

People drove a lot less in 2020, but motor vehicle accident deaths went up 9%. We will be looking at breakouts of the sub-populations where that mortality went up in 2020 over this three-part series. Today, let’s check out break out by sex and race/ethnicity.

More of a sex gap than race gap… until recently

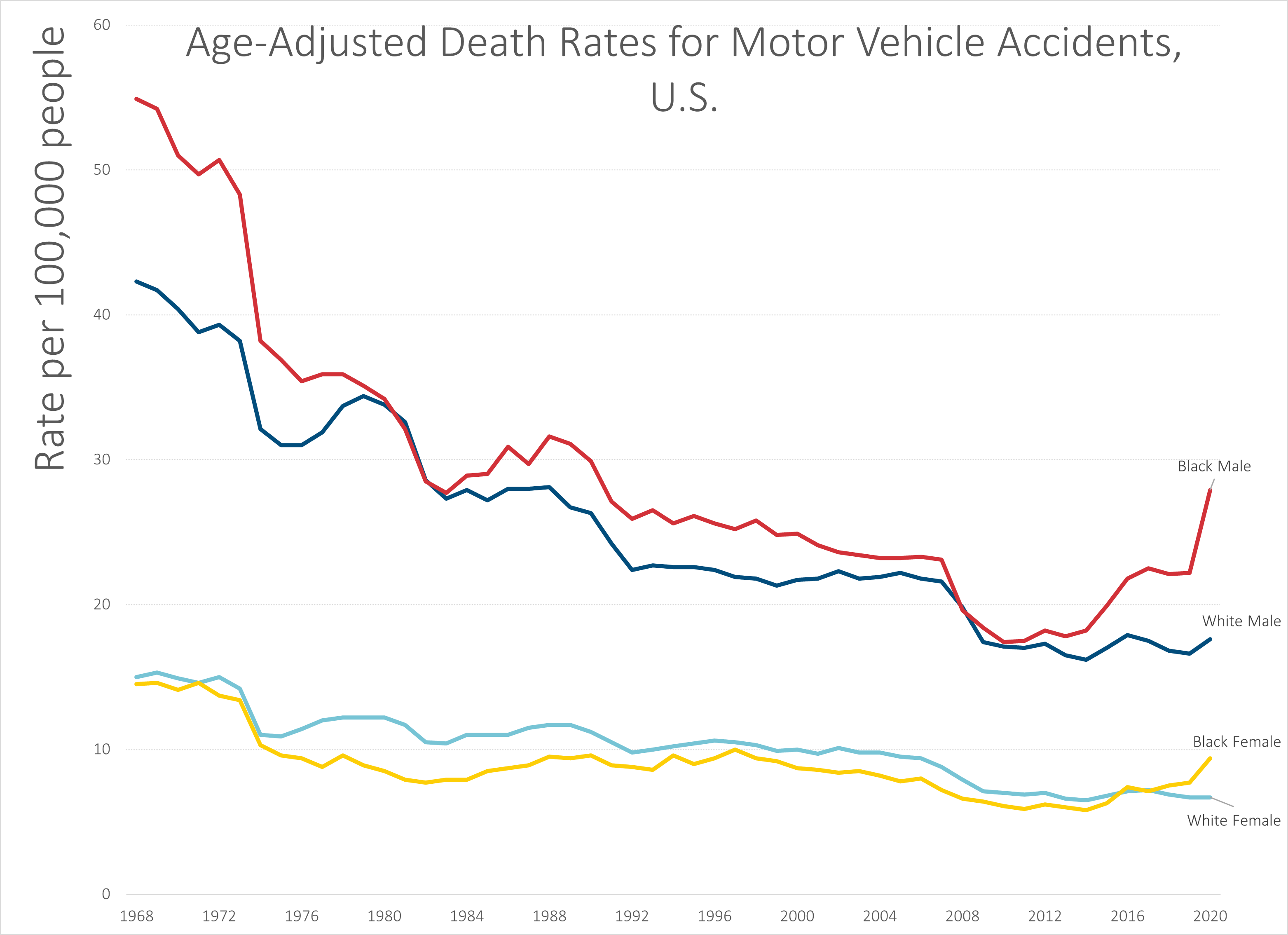

As before, the only races we have stats for going back to 1968 are black and white:

The gap is much bigger between the sexes than the races, especially up until about 2012. You can see black male motor vehicle accident mortality starting to increase at that point, while the other three groups are staying about level. That’s not a good trend. You can see the jump up in 2020, and we’ll get back to that change in a moment.

There’s not much of a difference between black and white female death rates for motor vehicle accidents. If anything, it was a little higher for white females.

We can get more racial/ethnic detail for 1999-2020:

I’m sorry to say that Native American male mortality statistics for external causes tend to be horrible.

It’s interesting that there seems to be “clusters” of rates, where Native American males were by themselves, then black males, which used to be clustered with Hispanic males, white males, and Native American females, but peeled off since about 2012.

And then there’s a big cluster of everybody else.

Change from 2019 to 2020: overall 9% increase, few groups decreased

If we did a table, we can see that black males had the highest increase in death rates, with a 26% increase. Given the relatively high age-adjusted death rate to begin with, that’s pretty substantial.

After that came black females, at a 22% increase.

There were a few decreases in rates: Native American females decreased 8%, Asian males decreased 5%, and Asian females decreased 16%.

That last one is pretty impressive, given Asian females already had the lowest death rate from motor vehicle accidents.

We will be seeing in upcoming posts the age-related and geography-related changes in death rates, and that likely had a large aspect to do with some of these differences by racial/ethnic groups. These groups are not evenly distributed geographically, with different states having different demographic percentages by groups. If some states had worse motor vehicle accident death rates than others, that may be related to these disparate changes — especially since we saw disparate trends before the pandemic for black males and Native American males in particular.

Federal policy and motor vehicle deaths

I do not want to spend much time on how federal policy has affected motor vehicle deaths, but it had helped make motor vehicles much more safe as time has gone on.

You can check out this data table and graph, which shows the relevant trend, but various federal efforts have improved traffic safety, I do not doubt. When we look at the effects of efforts to reduce drunk driving, improved quality of highway surfaces and grading, seat belt usage and airbags, other vehicle safety requirements — all of these have incrementally helped improve death rates.

All that said, I find the strategy report from the Secretary of Transportation to be idiotic: (I added the emphasis)

The status quo is unacceptable, and it is preventable. We know it’s preventable because bold cities in the United States, and countries abroad, have achieved tremendous reductions in roadway deaths. We cannot accept such terrible losses here. Americans deserve to travel safely in their communities. Humans make mistakes, and as good stewards of the transportation system, we should have in place the safeguards to prevent those mistakes from being fatal. Zero is the only acceptable number of deaths and serious injuries on our roadways.

Oh, for crying out loud.

Look, this is like saying “Zero is the only acceptable number of homicides in our country.”

What the hell are you going to do about it?

This is a ludicrous goal. Did they teach him about SMART goals at McKinsey? Or anything?

Some of the specific proposals are fine, some really aren’t relevant at a federal level (in my opinion), and some are really about trade-offs. There is a reason we have some fast and heavy vehicles on the roadways, shared with passenger vehicles. Interestingly, there were actually fewer fatal crashes involving heavy trucks (that is, semis) in 2020.

But given what I’ve seen with the 2020 and preliminary 2021 data, most of the excess motor vehicle accident mortality I’ve seen relates to drivers who really feel the need for speed. A lot of fatal crashes are one-vehicle accidents in which somebody has taken advantage of an open road, which were a lot more open as fewer drivers were out and about. That may be a self-correcting problem, actually.

Speed cameras are not about improving safety

However, one of the proposed fixes is speed cameras, and, well, I’m going to link to a few interesting stories and then say one more thing.

- 14 Feb 2022: Are Speed Cameras Racist? – New analysis shows that camera placement is equitable — but road designs aren’t

- 11 Jan 2022: Chicago’s “Race-Neutral” Traffic Cameras Ticket Black and Latino Drivers the Most

There are loads more articles where those two came from, but I picked the two that did the original research; the others tend to be derivative, and just look for people to quote.

This is my main comment: the traffic cameras/speed cameras/red-light cameras generally aren’t there to improve safety, and research generally has shown they don’t improve safety.

They’re generally there to raise revenue.

But yes, they’re catching people who speed. But have you ever dealt with a speed trap? I grew up in the south, and I have stories of being tailed by a cop car as the posted speed limit dropped from 35 mph to 25 to 15. For 2 blocks. That’s how they make money.

Anyway, maybe there’s something federal that can go on here, but these places, like Chicago, are still known for their level of corruption. I highly doubt any money spent on better traffic design would actually go to traffic safety. Rather, some well-connected people would be compensated and maybe some traffic lights get replaced. Oh, and they get some speed cameras.

So here’s hoping to some more traffic-choked roads, slowing down the speed demons, and getting the motor vehicle accident death rates back to a more reasonable level.

Which is not zero.

Related Posts

Cold Kills: Some Comparisons of Heat and Cold Deaths 1999-2020

Mortality Monday: Memorial Day and the U.S. Civil War

Mortality Monday: Chicago Shootings