Chicago and Illinois Pensions Watch: History and Who is Serious

by meep

I don’t mean “who is to blame”. Because that is, ultimately, irrelevant.

First, we start off with a a biglong feature from Crains:

There are many paths to failure. But to understand how Illinois’ pension system became the worst in the nation, it’s instructive to look at what happened 10 years ago in the final, hectic days of the annual state legislative session in Springfield.

A dense, 78-page bill aimed in part at curbing pension abuses in downstate and suburban school systems landed in lawmakers’ laps two days before their scheduled May adjournment. One sponsor called it the first “meaningful” reform in 40 years, a reversal of “decades of neglect and bad decisions.” Another predicted that it could save the state up to $35 billion.

But in addition to true reform, the bill later signed by Gov. Rod Blagojevich allowed the state to skip half its pension payments for two years and to stretch out some expenses approved under the previous governor, George Ryan. No one mentioned those could cost $6.8 billion. The math hadn’t been done.

……

A RAMP TOWARD DISASTER

But perhaps the most enduring culprit is the “Edgar ramp,” conceived in 1994 by Republican Gov. Jim Edgar as a 50-year program to stabilize the retirement systems.

Edgar set a goal of having the systems 90 percent funded by 2045. For the plan’s first 15 years, payment levels were set artificially low—effectively shorting the pension systems each year—and then ramped up significantly in later years. This allowed politicians to comply with the required payments at the start while hoping that future leaders would find billions of dollars down the road.

Now, with the systems still less than 43 percent funded, the state faces a crippling drain on its budget. In 1996, as the ramp required, only $614 million went to the pension systems. The amount due in the state’s 2016-17 budget year: a staggering $7.6 billion. That accounts for roughly 1 out of every 4 dollars in the state’s general fund, a trend that will continue for the next three decades.

Let’s see what that ramp looks like.

Yikes.

UNDERCONTRIBUTIONS RESULT IN UNDERFUNDEDNESS

They’ve got a graph that starts in 1996, and I’ve got one that starts July 1994. This shows the growth of the unfunded pension liability for the five state pensions, by cause. Watch the green bar — that’s the amount due to undercontributions.

In that 20 year period, about $40 billion additional of the unfunded liability is due to undercontributions.

The green bar was already at $7 billion in July 1994. In July 2014, it was at $47 billion. This is almost a 10% compound annual growth rate from 1994 to 2014. That is growing faster than the assumed growth on assets.

45% of the growth in the unfunded liability is due to undercontributions from 1994 to 2014.

You can check out this Google doc spreadsheet if you want to replicate my work.

Shortfalls due to undercontributions are a conscious choice on the part of the politicians. Especially when it causes the growth from this cause to grow faster than the discount rate.

It was a choice made every year for twenty years (actually, longer than that).

That portion grew every year — except in 2004, when there was the bullshit “contribution” from the pension obligation bonds. That wasn’t a real contribution — that was shoving a part of the liability elsewhere in the state’s balance sheet. It changed nothing.

LONG STORY SHORT

Now, there is more than just the Edgar Ramp described in that feature in Crain’s Business.

Reboot Illinois did a nice summary of the piece:

The causes can be boiled to the following bullet points:

1. In 2005, a bill delivered two days before session’s end was billed as saving the state $35 billion, but it allowed the state to skip pension payments for two years and stretch out others.

2. Underpayments from 1985 to 2012 add up to $41.2 billion, the nonpartisan Commission on Government Forecasting and Accountability concluded a few years ago.

3. In 1989, then-Gov. Jim Thompson agreed to creating a compounding 3 percent cost-of-living-adjustment.

4. In the late 1990s, another set of pension enrichments occurred.

5. Early retirement incentives to cut public jobs in 2002 by then Gov. George Ryan and Democratic House

Speaker Michael J. Madigan cost four times more than what was initially predicted.6. The stock market meltdown of 2008 and the dot-com bubble burst early in the 200s also added $15.9 billion in pension fund losses.

7. A downgrade in investment return assumptions in 2011 added another $9.8 billion in debt.

8. The pension ramp concept created in 1994 by then-Gov. Jim Edgar added to the problems. It set low funding contributions for the first 15 years and higher payments until 2045 on the unfounded hope billions could be found in later years.

Today, a quarter of every state dollar in the general fund must go to pensions and that rate will continue for the next three decades.

As I started my graph in July 1994, it did not capture many of these changes directly. Here is a graph going back to 1985:

You can barely see the benefit increases in there — that’s because that’s just a one-time hit. You change the benefits, and the benefits attributed to past service have to be recognized right then. Where the benefit increases are really showing up in, over time, are the undercontributions — as they’re not increasing the contributions to match this higher benefit level.

WHO IS SERIOUS ABOUT PENSION REFORM

That was history.

And while it is interesting to look at the various moving parts, it doesn’t really help address what should be done now.

Mark Glennon points out the history of the particular reporter who wrote the Crain’s piece, which is a good reminder. It can explain the emphases he puts on the Edgar Ramp, for instance, but I am pretty much in agreement: the primary cause of the pension shortfall are undercontributions.

So the obvious “fix” is to increase contributions, right?

Chicago Teachers don’t seem to think so:

Chicago Teachers Union President Karen Lewis said the district’s withdrawal of a one-year contract offer was “disingenuous, disturbing and destructive” and called efforts by the city to have teachers pay their full pension contributions “strike-worthy.”

The district’s decision essentially hits the reset button after months of talks. Both the union and Chicago Public Schools officials agreed to resume work on a new contract next week.

…..

A bigger issue going forward may be the city’s desire to have teachers pay a greater share of their pension contribution. Under the one-year offer, the district had agreed to maintain the long-standing practice of paying the lion’s share of teachers’ contributions to their pensions. Teachers have been paying only 2 percent of their total 9 percent contribution.However, Claypool said earlier this week that he doesn’t see a long-term solution to the district’s budget crisis that doesn’t involve the teachers covering their full share.

Lewis said Claypool has “apparently directed CPS not to honor the deferred payment pickup, (and) will impose a 7 percent pay cut in an effort to force us into another strike.”

“I’m saying that to take a 7 percent pay cut is strike-worthy,” she said. “That is not acceptable to our members. No one has agreed to that.”

…..

According to district records, the 9 percent employee contribution totaled nearly $164 million in the 2014 fiscal year. CPS, according to its financial records, picked up about $127 million of that amount and paid $613 million for its own contributions to the pension fund.

Chicago Teachers: do you or don’t you want to get your pensions?

Here is the development of the Chicago Teachers unfunded pension liability (only back to 2000):

Here is the distribution of the pension amounts in 2014 for retirees:

The blue line indicates how many retirees had that many years of service, and the red line indicates the average pension received by those having that many years of service. Most of the retirees do seem to have a full career’s worth of service, and the average pension increases as one would expect.

My work can be found in this spreadsheet.

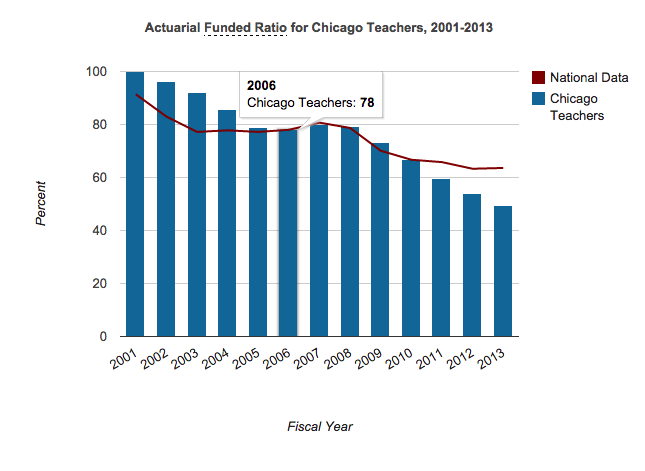

From the Public Plans Database, this is what the teachers plan’s funded ratio has done:

From 100% in 2001, down to about 50% in 2013.

This graph gives an idea of the funding shortfall:

I ask again: who should be paying these extra contributions?

Perhaps some of the teachers think they will die before the funds will run out. Perhaps some think there must be some extra money lying around in somebody’s pockets — rich people, the state, conventions that come to Chicago…can’t we get the federal government to chip in?

If it were only the Chicago teachers, perhaps they would.

But look to Detroit: they got their pensions cut.

HISTORY WIPED AWAY

I know Thomas Jefferson is getting the Damnatio Memoriae treatment right now, but let us see what he wrote to Madison as he watched the French Revolution get underway:

The question Whether one generation of men has a right to bind another, seems never to have been started either on this or our side of the water. Yet it is a question of such consequences as not only to merit decision, but place also, among the fundamental principles of every government. The course of reflection in which we are immersed here on the elementary principles of society has presented this question to my mind; and that no such obligation can be transmitted I think very capable of proof. I set out on this ground which I suppose to be self evident, “that the earth belongs in usufruct to the living;” that the dead have neither powers nor rights over it.

……

I suppose that the received opinion, that the public debts of one generation devolve on the next, has been suggested by our seeing habitually in private life that he who succeeds to lands is required to pay the debts of his ancestor or testator, without considering that this requisition is municipal only, not moral, flowing from the will of the society which has found it convenient to appropriate the lands become vacant by the death of their occupant on the condition of a paiment of his debts; but that between society and society, or generation and generation there is no municipal obligation, no umpire but the law of nature. We seem not to have perceived that, by the law of nature, one generation is to another as one independant nation to another.”The interest of the national debt of France being in fact but a two thousandth part of it’s rent-roll, the paiment of it is practicable enough; and so becomes a question merely of honor or expediency. But with respect to future debts; would it not be wise and just for that nation to declare in the constitution they are forming that neither the legislature, nor the nation itself can validly contract more debt, than they may pay within their own age, or within the term of 19. years? And that all future contracts shall be deemed void as to what shall remain unpaid at the end of 19. years from their date?

If we went by Jefferson, there could be no public pensions the way we know them today.

Not being able to have a debt that’s binding 20 years after it’s issued would put quite a crimp in the promises in public pensions. To be sure, we live longer now, but we need to remember that the pensions are asking people to pay decades into the future for service that was performed decades in the past.

Thing is, the payment of many unfunded pension liabilities is not “practicable enough”. Jefferson was speaking of a minor debt, and thinking through how much a people could fiscally bind untold generations.

Ex-Governor Edgar is still alive, as are many of the Illinois politicians that ramped up pensions and undercontributed to them, hoping that those untold generations would eventually pony up.

Those untold generations may not even show up.

CHOICES HAVE CONSEQUENCES

I understand that people will have fun pointing out that Edgar or Blagojevich or Daley or whoever is “most” to blame for the condition of Illinois and Chicago pensions, but the central choice is one that has been made, year-after-year, for decades. All are complicit.

That includes the people receiving the pensions.

If one allows a debtor to amass more and more debt they owe you, and you don’t do anything about it, then you are complicit when that debtor finally defaults.

And make no mistake: they will default on that debt.

So one has to make choices going forward. Yes, “full contributions” are a choice, and if you can’t get to full contributions within a reasonable time frame, you’re saying the pensions aren’t payable.

Taking benefit reductions are also a choice, but given Illinois court rulings, that will be allowed to come only through an amendment of the state constitution.

Spreading the pain around — so that teachers have to take a hit in total current compensation by having to cover their full 9% contribution — that would show some seriousness.

Maybe y’all can raise taxes to cover contributions, but remember neither Illinois nor Chicago is California or New York. There’s not a lot that’s attractive about the place (speaking as a lifelong coaster). And when one sees politicians raising taxes and then turning around to give public employees a raise, the suckers, I mean taxpayers, will realize they’re being had.

So what’s it gonna be, Illinois? What’s it gonna be, Chicago?

The shadow of Detroit and Puerto Rico overcasts you.

Related Posts

Public Pensions Watch: Choices Have Consequences

GameStop Follies: Hedge Funds, wallstreetbets, and Public Pensions

Asset Grab Bag: Whistleblower Award for Blogger, Private Equity Fees and Returns, and more