Social Security: The Annual Trustee Report - Cash Flows, Tardiness, and Other Views

by meep

The 2017 Social Security and Medicare Trustee Reports are out. I’m going to ignore Medicare and DI for now (because retirement income is enough for me to focus on — it’s so much simpler than health care.) Here’s the full report in PDF.

I will excerpt some from the summary text:

Social Security

The Social Security program provides workers and their families with retirement, disability, and survivors insurance benefits. Workers earn these benefits by paying into the system during their working years. Over the program’s 82-year history, it has collected roughly $19.9 trillion and paid out $17.1 trillion, leaving asset reserves of more than $2.8 trillion at the end of 2016 in its two trust funds.

The Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) Trust Fund, which pays retirement and survivors benefits, and the Disability Insurance (DI) Trust Fund, which pays disability benefits, are by law separate entities. However, to summarize overall Social Security finances, the Trustees have traditionally emphasized the financial status of the hypothetical combined trust funds for OASI and DI.

…..

The Trustees project that the combined trust funds will be depleted in 2034, the same year projected in last year’s report. The projected 75-year actuarial deficit for the OASDI Trust Funds is 2.83 percent of taxable payroll, up from 2.66 percent projected in last year’s report. This deficit amounts to 1 percent of GDP over the 75-year time period, or 21 percent of program non-interest income, or 17 percent of program cost.

…..

Social Security’s total income is projected to exceed its total cost through 2021, as it has since 1982. The 2016 surplus of total income relative to cost was $35 billion. However, when interest income is excluded, Social Security’s cost is projected to exceed its non-interest income throughout the projection period, as it has since 2010. The Trustees project that this annual non-interest deficit will average about $51 billion between 2017 and 2020. It will then rise steeply as income growth slows to its sustainable trend rate as the economic recovery is complete while the number of beneficiaries continues to grow at a substantially faster rate than the number of covered workers.After 2021, interest income and redemption of trust fund asset reserves from the General Fund of the Treasury will provide the resources needed to offset Social Security’s annual deficits until 2034, when the OASDI reserves will be depleted.

….

Under current projections, the annual cost of Social Security benefits expressed as a share of workers’ taxable earnings will grow from 13.7 percent in 2016 to roughly 17.0 percent in 2038, and will then decline slightly before slowly increasing after 2051.

I highlighted one line in particular — because the interest “income” is bullshit.

It’s the U.S. government charging interest on the IOUs it gives itself. The “Trust Fund” is a trust fund only in governmental naming. It’s an accounting gimmick that is easily wiped away by new laws; there is no actual legal protection like a true, private trust fund.

CASH FLOWS ARE REAL—ACCOUNTING IS NOT

That the actual cash taken in is less than the cash going out is the key thing.

I don’t want to belittle accounting. Accounting is important, as are projections, even if it’s laughable to think one can predict what will happen 75 years from now. I look at balance sheets and contingent liabilities (as in insurance, annuities, and pensions) all the time.

But they’re all ways of keeping score, and not terribly real to non-finance people.

Cash going in and cash going out is really real.

Let’s build this up. Data are from this table.

First, we’ll show what the components of income are for the Social Security (old-age and survivors) are:

Items to note:

- The large orange areas are the interest. It’s barely anything until the 1980s at which point the Boomers hit their peak earning years… and the FICA rates were increased.

- In 2012 and 2013 there were huge infusions from the General Fund (aka the big pot of federal money); this was due to a short-lived FICA rate reduction, but they didn’t want the Trust Fund to get depleted on paper, so they shoved money in from the regular taxes (and Treasury bond buyers)

- Taxation of benefits isn’t huge with regards to receipts…. yet.

I am going to throw out the “income” from the General Fund and Interest on the Trust Fund for the next graph.

To note:

- Cash outgo seems pretty steadily, exponentially growing.

- Cash income… not so much in the steady growth

Okay, now the moment of truth — what’s the net cash flow (excluding within federal transfers from interest and general funds).

That’s not a good trend.

Remember — even with assuming earning interest on the Trust Fund (albeit at current low rates) — the Trust Fund is projected to run out of money in a couple of decades.

My net cash flow graph shows that Social Security is a problem now, because current tax receipts can’t cover current benefits. Pay-as-you-go worked fabulously while the truly demographic bumper crop of Boomers were working and paying into the system. Thing is, the oldest Boomers have been Social Security eligible since 2008, and the peak year of Boomer births (1957/1958) are coming up on Social Security eligibility.

Social Security is not a problem when the Trust Fund, accounting score-keeping-on-paper mechanism, runs out. Social Security is a problem right now, because it takes General Fund money (i.e., the big pool of taxes and bond sales) to cover the cash flows. This has been the case since 2010.

GET ME THE REPORTS ON TIME

The following piece ran 20 June 2017: With This Social Security Slip-Up, Trump Is Following in Obama’s Footsteps

Donald Trump and Barack Obama probably don’t agree on many things, and their views on Social Security reflect very different approaches to the system. Yet at least in one respect, the two U.S. presidents agree on Social Security: Neither one’s administration met its legal responsibility to have the trustees of the Social Security Trust Fund issue their annual report in a timely manner. With the report already more than two and a half months late, it’s unclear whether President Trump will end up doing a better or worse job than President Obama did in getting information to the public about Social Security’s financial prospects.

What the government is supposed to do

Every year, the trustees of the Social Security Trust Fund are required to give a report about what’s happened with the program’s finances. In particular, Section 201©(2) of the Social Security Act makes it clear that the trustees must report “on the operation of the Trust Funds during the preceding fiscal year and on their expected operation and status during the next ensuing five fiscal years.”

…..

The federal law also mandates a timeline for the trustees to make their report. If the report is made later than the first day of April, then it’s considered late under the provision. However, there’s no stated penalty for being late in the law.

A history of tardiness

In President Obama’s eight years in office, the Social Security Trustees — which include the secretaries of the treasury, labor, and health and human services, as well the commissioner of the Social Security Administration — never issued their report on time. The best effort they made was in 2012, when the report was sent to Congress on April 23. Their worst offense came in 2010, when the report wasn’t transmitted to lawmakers until Aug. 5.

Meanwhile, President Trump has already missed the April 1 deadline, and it’s unclear when the 2017 Social Security Trustees Report will be available. As with all incoming administrations, the need to confirm cabinet members led to some discontinuity in the months leading up to the deadline. Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin wasn’t confirmed until Feb. 13, and Tom Price wasn’t confirmed to run Health and Human Services until Feb. 10. With the failed nomination of Andy Puzder to head up the Labor Department, eventual Labor Secretary Alex Acosta wasn’t confirmed until April 27. Nancy Berryhill was named acting commissioner of the SSA on Jan. 23, but the agency hasn’t had a confirmed commissioner since early 2013.

The actual date of the 2017 report release? You can find it a few pages in, on the letter of transmittal. You can find it every year — this year it was July 13.

Anyway, my brain has been fried looking at stuff at work on interest rates and bond spread, so let’s have some fun and just look at dates for each year. Here I have graphed the date for the release of each report… going back to the very first report in 1941. I don’t have the dates for 1943 and 1946 as they didn’t include the letters of transmittal for those.

The big black line is April 1.

Yes, some of the years, the reports came out on January 1 or near to it. From 1951 to 1960, the reports were transmitted on March 1. Maybe those used to be the due dates. I’m certainly not looking that up. I’ll just assume it was due April 1 every year.

I’m going to focus on the years 1993 – 2016, covering the Clinton, Bush, and Obama administrations.

Lookie there. So Bush’s admin made the deadline 6 out of 8 times, Clinton’s 3 (I’m including the 1995 one, delivered April 3, as being on time. Though it wasn’t), and Obama’s never. Another long stretch with late reports: 1971-1981 (Nixon, Ford, and Carter).

[way way tangent — I went digging into why the two years for the Bush tardies, and one year, 2006, involved a dispute over the public trustees (which we don’t have right now) and I spent too long looking into the times there were no public trustees and…. ultimately, I realized it was bullshit. It didn’t matter. It was preening over something stupid that never made a difference in the first place. I wish some of the professional journalists deleted as much as I do.]

Here’s a histogram as to how many days before/after April 1 the reports were sent:

Okay, Trump, don’t make them impeach you over a late Social Security Trustees report. You are on notice.

COMMENTARY

Okay, enough from me. Let’s see what other people have to say. Not all of them are reacting directly to the report, but many are.

Steve Vernon: Why all the pessimism over Social Security?

In what has become an annual ritual [THIS IS NOT A RECENT RITUAL], the Social Security trustees issued a stern warning this week to Congress in their latest report on the state of the federal retirement program and of Medicare. Their conclusion:

“Lawmakers have many policy options that would reduce or eliminate the long-term financing shortfalls in Social Security and Medicare. Lawmakers should address these financial challenges as soon as possible. Taking action sooner rather than later will permit consideration of a broader range of solutions and provide more time to phase in changes so that the public has adequate time to prepare.”

Those findings had a familiar ring, echoing the same concerns the trustees have expressed for years about the funding level of Social Security and Medicare. What they gloss over is the viable long-term solutions for these issues.

Over the course of Social Security’s 82-year history, the Social Security Administration has collected roughly $19.9 trillion in payroll taxes and other income, and paid out $17.1 trillion in benefits and other costs. This leaves asset reserves of more than $2.8 trillion at the end of 2016 in the two funds (Old Age and Survivors Insurance, and Disability Insurance).

The annual report typically focuses on the combined trust funds, referred to as the OASDI funds. The trustees forecast that the combined trust funds will be depleted in 2034, the same year as projected in the 2016’s report. The projected 75-year actuarial deficit for the OASDI Trust Funds is 2.83 percent of taxable payroll, up from 2.66 percent projected in last year’s report. This deficit amounts to 1 percent of the U.S. GDP over the 75-year time period covered by the report.

Under current law, if the trust funds are depleted, then benefits will be reduced to the level that can be funded through payroll taxes collected from all workers employed at the time. The 2017 report projects that about three-fourths of benefits could be paid after 2034 if the fund is exhausted and Congress doesn’t act to shore up the funding.

This is an important item to understand. If the trust fund is depleted, retirees would not have their benefits completely eliminated, as many people believe. Of course, a 25 percent haircut would be very bad news. However, Social Security’s funding challenges cause many people to be too pessimistic, and believe they won’t get anything from Social Security.

Jake Novak: Social Security is fueling income inequality. Let’s end it

Social Security is a misleading scheme and it’s going insolvent anyway.

It was sold as an insurance plan, but it’s really income redistribution that takes money from the less wealthy and gives it to the more wealthy.

It’s time to phase out the program and give a real boost to the economy.What if there was a financial scheme that took the money of younger working people and gave it to older richer people year after year?

What if that scheme relied heavily on a misconception that the money collected was being set aside for the contributor to get back at a later time?

And what if despite the fact that the law required every wage earner and employer to pay into this scheme, it still was running out of funds and spiraling toward disaster?

Actually, there’s no need for “what ifs” because that scenario is actually happening, and has been happening for more than 80 years. It’s called Social Security and it’s way past time to end this scam if we want to keep the American dream alive.

The latest evidence came this week when the Social Security trustees released their annual report to the public. The report projects that the so-called Social Security trust fund will be tapped out by 2034, and at that point Social Security beneficiaries would have to start taking 77 cents on the dollar for their promised benefits. In other words, if you’re a wage-earning worker 48 years old or younger, say goodbye forever to a good part of that paycheck withholding money.

It’s not like any of this should come as shock to most of the people who will be affected. Gallup’s polls of Americans aged 49 and younger have consistently shown that a majority of those Americans do not believe they will get Social Security benefits when they reach retirement age.

….

If the answer is because most Americans still want to help the elderly get by, that’s a nice sentiment but it’s misplaced. Older Americans aren’t just doing okay. The latest extensive study of age-based wealth in the U.S. shows that a typical household headed by an adult 65 and older has 47 times the net worth of a household headed by younger Americans. Yep, Papa and Granny are loaded.Now, helping older people who happen to be poor or on the margins of poverty is something different. But the cultural assumption many of us have about elderly folks needing more financial help in America is pretty much the opposite of the truth.

And Social Security is one of those things that’s currently siphoning income from younger workers and giving it to older Americans who statistically need the money a lot less than the people providing it to them. That makes Social Security a bad case of Robin Hood in reverse.

Bill Bergman: Welcome to your government’s financial future, children

Yesterday, the Social Security Board of Trustees issued the annual report on the condition of the “Trust Funds.”

The report showed some marginal deterioration from the report last year, while the estimated insolvency date (2034) was unchanged from last year.

That’s just 17 years from now.In arriving at the appraisal of Social Security finances, the Trustees report includes projections for tax revenue and benefit spending over a 75-year forecast horizon. These include projections underlying both an “open group” as well as “closed group” perspective. The “open group” is based on current and future participants, while the “closed group” perspective excludes future participants.

In the most recent Trustees’ report, Social Security’s open-group unfunded obligation was reported at $12.5 trillion, compared to the $11.4 trillion estimated in the 2015 report.

Truth in Accounting believes a “closed group” perspective is valuable. In stripping out the present value of revenues and expenditures for future participants, the closed group perspective sheds light on issues relating to intergenerational equity.On a “closed group” basis, the unfunded Social Security obligation (roughly $30 trillion) reported in the 2016 Financial Report of the U.S. Government was over twice as high as the “open group” estimate.

….

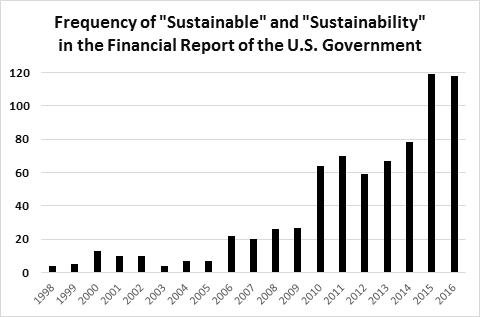

Addressing questions about the sustainability of government finances can get pretty complex. However, in complex situations, you can sometimes do simple and informative things.The first chart below shows the number of times the words “sustainable” or “sustainability” appeared in the Financial Report of the US Government from 1998 to 2016.

Things have been heading North, as concerns about the sustainability of Uncle Sam’s finances have intensified.

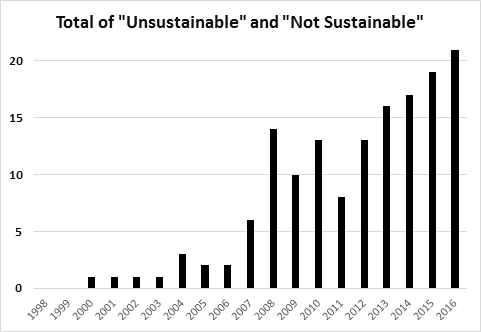

In turn, the next chart reports the number of times the words “unsustainable” or “not sustainable” have appeared in the same report, over the same time period.

Interesting approach to analyzing these things.

Charles Hughes: Social Security Slouches Towards Insolvency

Social Security is by far the largest government program, disbursing benefits to 61 million people with total expenditures of $922 billion in 2016. The program continues on its unsustainable fiscal trajectory, highlighted once again by the 2017 Social Security Trustees Report released on Thursday.

The Trustees report that the long-term actuarial deficit has worsened considerably, and America is one year closer to the projected trust fund exhaustion in 2034. Putting Social Security back on sound financial footing requires comprehensive reform, but there is little appetite for discussion of serious proposals. With each year of inaction, the fiscal outlook for the program gets bleaker, and the magnitude of the changes that will eventually have to make get larger and even more highly concentrated on younger generations.

Each year since 2010, Social Security has been operating at a cash flow deficit, meaning the annual costs exceed income from payroll taxes and the taxation of benefits. In 2022, the annual program costs will be more than total income, which also includes interest on the trust fund assets. At this point the trust fund will be drawn down. By 2034, the trust fund will be exhausted, at which point tax income would only be enough to pay for 77 percent of benefits. A person born in 1967 will reach full retirement age in the year the trust fund is projected to run out. Millennials will still have decades left in their working lives when Social Security is exhausted, and will live under a cloud of uncertainty until reforms are enacted.

The reports use a 75-year window for long-range solvency of the program, and the actuarial deficit over this period increased 6.4 percent relative to last year’s report. The present value of unfunded obligations over the 75-year window is $12.5 trillion, about $1.2 trillion more than in last year’s report. Some of the worsening is the changing projection period: as the fiscal situation deteriorates over time, moving the window forward with each successive report worsens the outlook. The shift in the valuation period only accounts for about 29 percent of the increase in the long-term deficit, while the “effects of recently enacted legislation, updated demographic and economic data, and improved methodologies” accounted for the rest of the increase.

Long-term demographic trends are a significant contributor to these problems. Due to the aging of the population and falling fertility rates, there are fewer workers for each beneficiary than in the program’s early years, which strains the financing. In 1950, there were 16.5 covered workers per beneficiary, and last year there were just 2.8. Absent immigration, this ratio will fall even further to 2.1 by 2036.

The imbalance in Social Security’s long-term outlook is predictable and unlikely to change, but that has not translated into a willingness to grapple with Social Security reform in a serious manner. The cost of inaction is high, as conveyed by the new report.

For illustration, to make the program fully solvent through the 75-year projection period, scheduled benefits would have to be immediately and permanently cut by an amount equivalent to 17 percent for all current and future beneficiaries. If no substantial reforms are enacted until the trust fund becomes exhausted in 2034, the benefit reduction would have to be 23 percent. As large as these required changes are, they assume that the reductions would apply uniformly to current seniors and future beneficiaries alike.

He made an “interactive” graph, which is silly with a simple data set like this. The data are from here.

ACTIVE WORKERS VERSUS SOCIAL SECURITY BENEFICIARIES

Let’s start out with the absolute numbers — we’ll get to ratios soon, but I think this is understood.

That’s actual historical numbers, so you see there are almost no beneficiaries and a slow rise for some time in the 1940s-1950s. Note: I am only graphing numbers of workers and beneficiaries… not the cash flows (see above).

So now let’s switch to ratios, and include the three projections — low cost, intermediate cost, and high cost. These mainly differ with respect to demographic numbers, such as fertility and immigration rates.

That is not a helpful graph. I can’t see distinctions in the projections because of the insane ratio in the early years of the program, where loads of people where paying taxes and almost nobody was getting benefits.

So let’s restrict it to starting in 1965, when enough people were drawing benefits, and let’s not project past 2050, because that’s absurd enough in our overconfidence in projections.

There is one thing I want you to take away from this close-up graph: that the ratio of workers paying into the system versus beneficiaries will continue to decrease for some time, even in high fertility/immigration assumption sets. Part of that is because of the baby bust in the 1970s — sorry, no more people born in the 1970s are getting created right now. Some may immigrate, but it’s not a huge number.

Related Posts

State Bankruptcy and Bailout Reactions: More Reactions

Taxing Tuesday: Lazy Days of Summer

Taxing Tuesday: Look Back to Olden Times and What Awaits Us in 2021