Teacher Pensions: A Big Problem for Many States

by meep

For Teacher Appreciation Week, I made a video about my favorite teacher: give it a watch. That video is all positive.

What I have below is not.

TEACHER PENSIONS ARE A PROBLEM BECAUSE THERE ARE SO MANY

Teacher pensions are a huge problem for states for a variety of reasons. The main reason is they are far-and-away the largest government employee category for state and local government. There are far more teachers than cops or firefighters. Way more than people working in City Hall.

These data are from 2014, but the data from only 5 years later is unlikely to be different. I also found broad data from FRED, so you can see how much education takes up in employment.

So, let me show you the non-seasonally-adjusted data of what percentage of state and local employees are in education.

If I am interpreting this correctly, this is number of employees. The following is the number of FTEs (full-time equivalents) from March 2014:

Here is a pie chart version:

I want to extract the following remark before continuing:

Data are not intended to measure government efficiency or quality of public services.

Hey now. No need to be bitchy.

Okay, enough jollity.

Here is my main point: the big reason that both teacher pensions and pay are a huge deal for state and local budgets is that they are a huge portion of state and local government. It’s none of this FOR THE CHILDREN stuff, or SCHOOL-TO-PRISON PIPELINE stuff. It’s just that there really are more teachers than any other category, and of government employee salaries, they represent a huge percentage.

That’s all.

It’s a lot easier to bump up salaries and pensions to only 11% of the payroll (which is police + firefighters) than to something that’s the majority of your employment budget (teachers + professors, at 62% of FTEs and 59% of payroll.)

People may love the teachers, but a pay and benefits boost to them have a much larger effect on government budgets compared to boosting other categories.

I understand people prefer to do politics in emotional terms, and this is numerical terms. But the numbers do bite. No matter how much it hits you in the feels.

TEACHER PENSIONS ARE PROBLEM BECAUSE TEACHERS ARE LONG-LIVED

I will not do this one today. It’s not just a matter of teachers being primarily female. Given that public pensions generally extend to spouses, and most people are heterosexual, you get plenty of women appearing in the more-male-dominated profession of firefighting.

But the issue is that both women and men who are public school teachers tend to have better mortality than men and women in other pension plans.

I will look at that in a later post.

TEACHER PENSIONS ARE A PROBLEM DUE TO STATE FUNDING OF LOCAL TEACHER PENSIONS

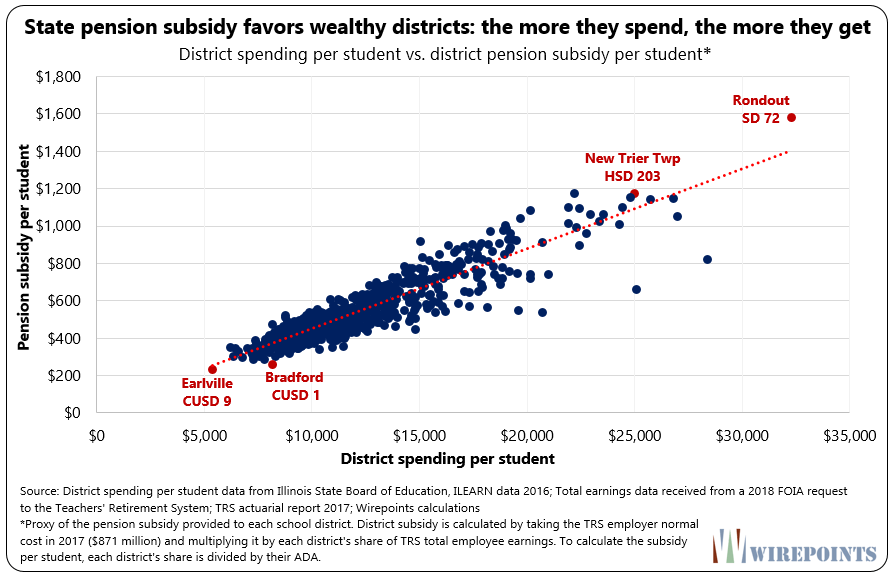

This is the really ugly bit. Rich school districts get outsized support for teachers’ pensions compared to poor school districts. In many states, the employers (localities) who are setting the wages are not picking up the full cost of the teachers’ pensions, but are funded by the state.

Not all states structure their teacher pension systems that way, but many do.

How state pension subsidies undermine equity

When policy advocates debate how best to ensure equity in public education funding, they tend to focus on a single question: How much aid should states give to cash-strapped school districts? Rarely does the topic of teacher pension reform come up. But, in fact, pensions represent a very large and fast-growing source of education spending, much of it distributed in ways that are, in a number of states, anything but equitable. Specifically, when the state government pays district pension costs, this can have a massive distortionary effect on the distribution of state education dollars, threatening to undermine (and, in at least one state, completely negating) other efforts to achieve equity between rich and poor school districts. We’ve found in our own research that although state pension subsidies receive limited public scrutiny, they’re a major source of inequity in school finance.

It’s a simple concept. When the state takes responsibility for local teachers’ pensions, then you know the higher-paid teachers have pensions that cost more. And the state is picking that up?

Yup, especially in places like Illinois and Connecticut. It’s a huge issue in both those states, because both states have some super-rich, and some super-poor, school districts.

As recent research has found, the ways in which pension contributions are distributed can have implications for equity (Griffin-Johnson et al., 2012; Marchitello, 2017). When the state makes pension payments on behalf of school districts, it may distribute those funds inequitably, and the distribution tends to favor districts with high property wealth and low student poverty. Wealthy suburban school districts often pay their teachers significantly more than less affluent districts are able to do. So if the state funds pensions based on a percentage of each salary, it pays a higher dollar amount for teachers in the wealthy school district.

In our own studies, we’ve drilled down deeper into the ways in which pension subsidies function. All previous work on this topic has had to rely on researchers’ assumptions about pension costs, as a share of payroll, because pension funds such as Illinois TRS did not publish district-level data. This has now changed. New accounting rules force pension funds to account publicly for the amount of subsidy that districts receive through state pension payments, revealing more of the details of where the money goes.

Fancy that. More information leads to seeing how that sausage is made.

Take, for example, the teachers Ms. Poor and Ms. Rich. They are identical in almost every way. They both have 10 years of teaching experience and have master’s degrees from the same university. They each teach 2nd grade and have 20 students in their class. The only difference is that Ms. Poor works in a less affluent school district than Ms. Rich, and while Ms. Poor makes $50,000 per year, Ms. Rich makes $70,000.

Let’s assume the state pays 10% into the pension fund for each teacher. That means the state pays $5,000 into the retirement fund for Ms. Poor and $7,000 for Ms. Rich. If we divide each sum by 20 — the number of students in the class — we see the state is paying $350 per pupil for Ms. Rich’s students, but just $250 per pupil for Ms. Poor’s students. (Of course, this is just a hypothetical. In real life, class sizes would likely be higher in Ms. Poor’s classroom, making the per-pupil funding even less equitable.)

It’s not terribly complicated.

In 2018, Wirepoints published Illinois’ regressive pension funding scheme: wealthiest school districts benefit most – Wirepoints Special Report

Rather than dig into the details (you can follow the link), let’s just look at this:

It reminds me a bit of college subsidies, too. Many of the poorest students get nothing, because they don’t have good enough education to get into college to begin with, or it’s too tough for them to fit college with their working lives. Somebody like me, with scads of opportunities and parental support, gets NSF grants and yadda yadda.

Heck, look at this graph.

That’s the clearest linear model I’ve seen from real-life data in a long time.

TEACHER PENSIONS ARE A PROBLEM BECAUSE NEWER TEACHERS ARE PAYING FOR OLDER TEACHERS’ PENSIONS

Now, this one is specific to Illinois. Other states may also have this problem, but it’s extremely obvious for Illinois because the teachers’ pension plan, Illinois TRS, has two tiers of benefits.

The employee contribution for the Tier II teachers is more than their normal cost. The normal cost is the value of the benefit accrued for current work (as opposed to bits that have to amortize the unfunded liability).

Here is what you should look at from the most recent valuation of Illinois TRS.

I want you to look at this table, and I will point you to the numbers of importance:

Look at the numbers in parentheses for Tier II. That’s the employer’s normal cost, and the parentheses means negative numbers. Why are they negative? Because the Tier II employees contribute more than their normal cost.

They are subsidizing the older workers, explicitly.

In the projection, they are spending 1.75% down to 1.5% of their salary to pay for Tier I teachers. That’s not for their own benefits at all.

Many times the subsidy is implicit for these things, where the older employees are being subsidized via the amortization of the unfunded liability. But this is the normal cost, meaning newly accrued benefit value, not merely the growth of the old liability you keep inadequately funding.

Some have called into question the legality and the constitutionality of this, but no one has yet sued over this, as far as I know.

TEACHERS PENSIONS ARE A PROBLEM BECAUSE THEY ARE GROSSLY UNDERFUNDED

Again, this isn’t special to teachers. It’s just that there are so many, and the pensions cost a lot more than assumed (for a variety of reasons), that it gets expensive rather rapidly to fully fund teachers pensions.

I will not do an analysis of this right now, but you need to realize that teachers’ pensions aren’t underfunded out of spite against the teachers, but that they are such a huge part of the budget that there’s not much you can cut elsewhere to fill what they need.

Which is why Illinois had been looking at yet again underfunding Illinois TRS, but they got lucky with a windfall of unexpected tax revenue. Evidently.

But I will be writing about that on the next Taxing Tuesday.

HOW TO APPRECIATE TEACHERS: TAKE THE PENSION PROBLEM SERIOUSLY

Taking the problem seriously does not necessarily mean yelling BUT IT’S A PROMISE!! and wishing the money will appear to pay for the pensions.

Many states will require coughing up more money and can probably cover their promises.

But so many states will not be able to. There is a limit to how much the taxpayers can cough up, and you can pretty much default on current bondholders, with good luck in trying to get new ones.

But taking this seriously means understanding that the problem needs to be dealt with transparently, without trying to rush through a half-assed “solution” (cough Kentucky cough), and the problem needs to be dealt with before these pensions get into an asset death spiral. And definitely before the assets run out. That can take a long time, to be sure, but unsustainable systems are not a way to appreciate teachers.

This does not mean dumping DB pensions entirely, not necessarily, but the de facto trajectory of many places is to run the DB pensions into the ground all the while saying there’s no crisis til the money fully runs out.

And that’s not very appreciative.

Related Posts

Taxing Tuesday: Lazy Days of Summer

Friday Foolery: More Centless in Seattle! And Cook County Regrets?

Public Pensions Watch: Choices Have Consequences