Illinois Pensions: How Did We Get Here? Where Will They Go?

by meep

This is a combination & edit of two older posts, both from May 2015: Illinois Pensions: How Did We Get Here? The 1970 Constitution and Illinois Pensions: How Did We Get Here? Development of Unfunded Liability, as well as updating a few graphs to the most recent data I can get (FY2018).

There are two parts of the problem — one being the choice to short-change the pensions, the other being unable even to make minor changes to pensions under the current state constitution.

The Illinois State Constitution prevents pension reform

In May 2015, the Illinois Supreme Court struck down a set of pension reforms passed in 2013. This result should have surprised no one, and it certainly didn’t surprise me.

The ruling was based on a specific clause in the Illinois state constitution. The current constitution was put together and ratified in 1970.

Let’s take a look at the specific clause in question: Article XIII, section 5 of the Illinois state constitution.

I tried to find out what was written at the time. The following is an informational brochure on the constitution, I assume for those voting on it.

The bit we want is on page 16. I took a screenshot:

For convenience, this is what the text says:

SECTION 5. PENSION AND RETIREMENT RIGHTS

Membership in any pension or retirement system of the State, any unit of local government or school district, or any agency or instrumentality thereof, shall be an enforceable contractual relationship, the benefits of which shall not be diminished or impaired.

That was the language that went into the Illinois state constitution and was passed.

Within the brochure is this explanation of the text:

This section is new and self-explanatory.

Indeed.

The Illinois Supreme Court has always interpreted the language broadly

I am not interested in semantic deconstruction in this matter, and the Illinois Supreme Court has already interpreted this clause to mean a few things:

- you cannot change the percentage of cost-sharing on retiree health benefits, even if the specific procedures covered keep changing and health costs rise

- it doesn’t matter if you haven’t worked those years yet, not only are COLA benefits locked in for your past services, but also your future services

(at least, this is my reading of the rulings. I am not a lawyer, much less an Illinois constitutional lawyer.)

Yes, they knew what they wrote and what it meant

But let us consider what the people at the time said about this new clause, eh? Maybe we’re reading into it that which was never considered as a possibility.

Or maybe they knew just what they were doing:

And the transcript of the debate on that July day makes it clear that even the delegates who argued against the pension clause did so because they saw it as something that could handcuff state and local officials as they sought to prioritize spending in tough times.

“This innocuous little amendment sounds a lot like motherhood and strawberry shortcake,” complained delegate John C. Parkhurst, of Peoria, who went on to deride it as “terribly, terribly mischievous.”

Another critic wondered if the state might be locking its employees into a retirement anachronism if better and more lucrative funding mechanisms were developed. “To freeze this in the constitution might hurt the very, very people that we are trying to help at this time,” said Southwest Side delegate Ted Borek. Eight years later, the federal tax code was changed to allow the first 401(k)-type retirement plans.

Ann Lousin, then a young lawyer on the convention staff, recalled in a recent interview that the intent of the clause was quite clear. “Both proponents and opponents were saying that this would be a very strong protection for public employees, even though some felt in the future it might be regretted,” said Lousin, who now teaches Illinois constitutional law at Chicago’s John Marshall Law School.

……

Believe it or not, the state’s key pension funds were in almost as bad financial shape back then as they are now, and for the same reason: a chronic failure by lawmakers to pay enough money into the funds to cover projected pensions costs and keep them financially sound.Prevailing case law in Illinois and several other states had defined pensions as essentially bounties offered up to public workers that government bodies were free to reduce or eliminate at will. Fearing that just might someday happen, employees at state universities began agitating for including a safeguard in the new constitution.

At the same time, police, fire and other local workers grew nervous about new home rule powers the convention appeared set to bestow on local governments. They feared municipal leaders, flexing newfound fiscal independence from state rules, would see that as a green light to back away from retirement promises and spend resources on other things.

…..

Green said the wording of the pension clause was modeled after that added to the New York Constitution in 1938 to prevent that state’s Depression-era lawmakers from cutting money owed pension programs. He said in New York it had led to full funding of pension programs.But then, in a perhaps fateful declaration foreshadowing the present crisis, Kinney went on to stress that sponsors intended to protect benefits but did not consider their proposal a full-funding mandate. “It was not intended to require 100 percent funding or 50 percent or 30 percent funding or get into any of those problems,” she said.

In short, state and local governments would be required to keep their pension promises but not be required to sock away enough money to cover payments years into the future. When it came to funding, officials of both parties in Illinois took significant advantage of the escape clause, helping them skate by for decades without having to make politically difficult decisions on raising revenues or cutting services to meet pension obligations.

In May 1971, just weeks before the new constitution would go in effect, an official state pension oversight panel of lawmakers and laymen issued a report warning that the new pension safeguards were a mistake.

Didn’t matter. They did it anyway.

They haven’t changed it in fifty years

Since then, there have been two votes on amending the Illinois state constitution. It’s not been amended (to be fair, I don’t know if any proposals to amend Article XIII, Section 5 were in either of those votes.) Wonder what the result would be if they tried again. (The last vote was in 2008.)

Anyway, yes, this problem was known (before I was born) and they went ahead anyway. As it was, the population of taxpayers was still growing — who cared if future generations had to pay for past service?

Of course, if that taxpayer base didn’t grow fast enough…. oopsie.

This is not a “mistake”.

They knew what they were getting to in 1970.

They just assumed they’d all be dead before the bill came due.

Some were correct. Others…. not so much.

The deliberate underfunding of Illinois pensions

One of the biggest disputes in the public pensions brou-ha-ha is who is at fault with regards to underfunded pensions.

Mind you, there’s plenty of blame to go around.

But it would be nice to quantify the sources of the underfundedness, wouldn’t it?

Well, luckily, part of many of the publicly-available reports on pensions is an analysis of the change in the unfunded liability during the year. If you look at one year in isolation, you may get a misimpression of where the fault lies — after all, usually any one year of development is going to be dwarfed by the already huge unfunded liability.

So I decided to push back to long enough ago that the starting point would end up being dwarfed by the final unfunded liability. How about end of fiscal year 1984? Is more than thirty years of development long enough for you?

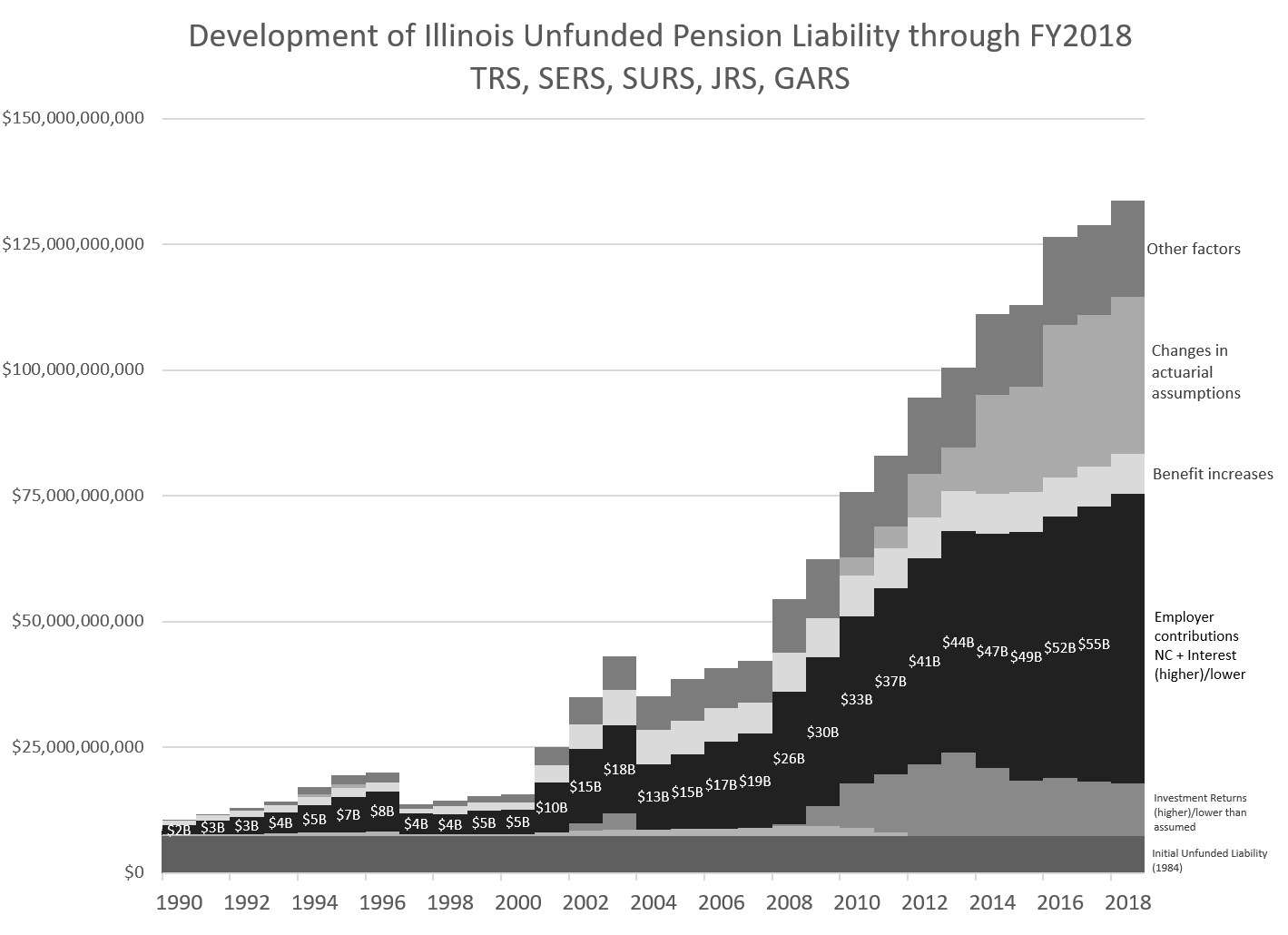

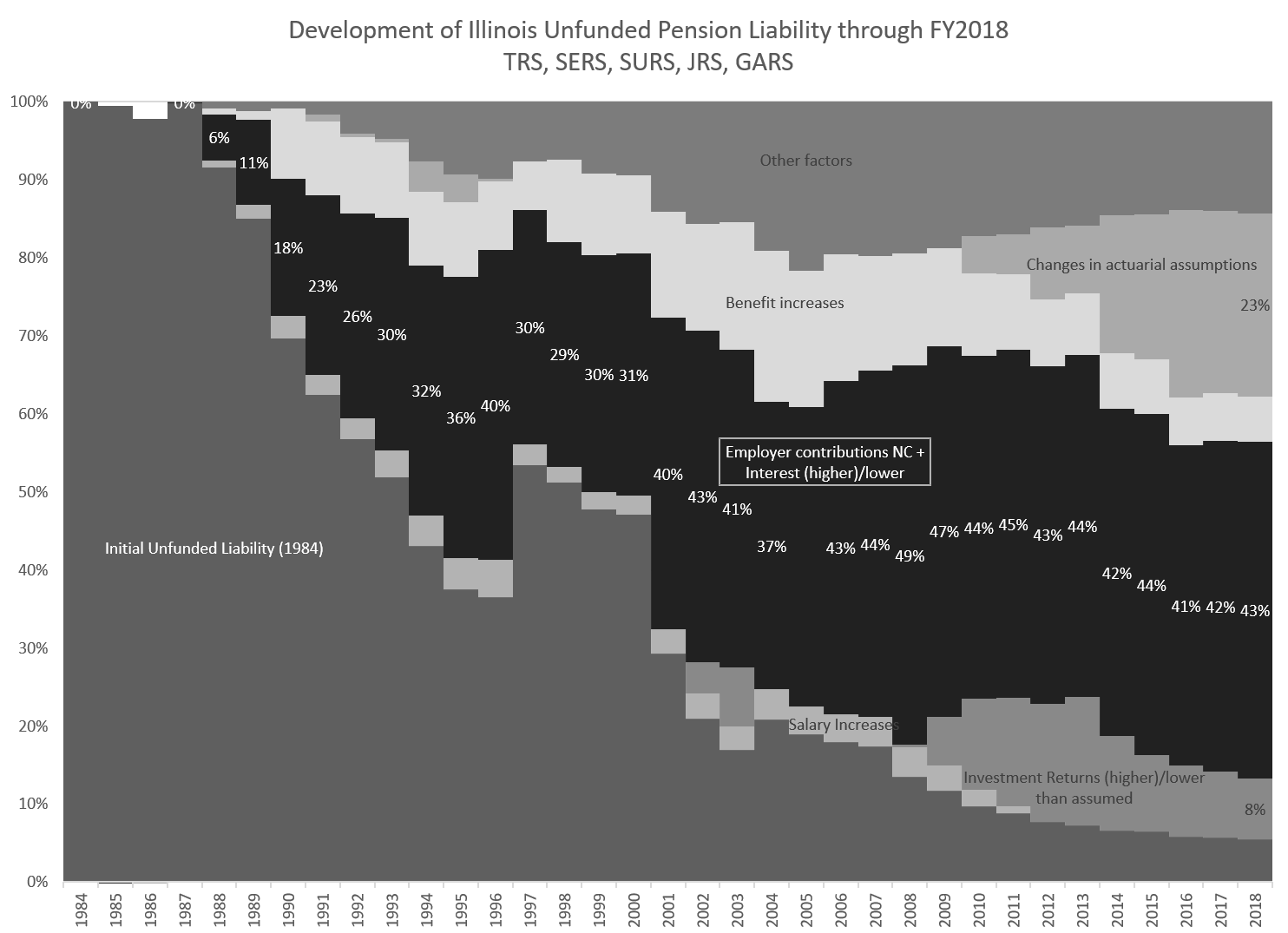

There is a lot going on in this graph, so let me explain how it was developed.

First, the information backing this graph can be found in this spreadsheet, and I list my original data sources as well. It is all based on publicly-available data. This encompasses the main Illinois state pension funds: Teachers Retirement System, State Universities Retirement System, State Employees Retirement System, Judges Retirement System, and General Assembly Retirement System. For the above graph, all funds are combined.

Graph interpretation

The constant grey bar across the bottom is the initial unfunded liability, as measured on 6/30/1984. Obviously, as time goes forward, that amount never changes. That was $7 billion.

Each year, I add onto the changes in the unfunded liability, color-coded by cause. This is cumulative, so that the top point of each column represents the total unfunded liability. For FY2018, that was $134 billion.

The vertical axis is nominal dollars – it’s not inflation-adjusted, it’s not in units of thousands of dollars. I wanted to keep all the zeros in because when you see $125,000,000,000 in all its glory, it hits you a bit more than “100 billion”. I did have to abbreviate for the data labels to make them fit, but I would prefer to use the full numbers. I think something like $55 billion looks innocuous, where $55,000,000,000 is a very big number indeed.

Two main features of this graph

- The unfunded liability is positive every year — the pensions have never been fully-funded

- The unfunded liability decreases a couple times: the late 90s, I believe that was recognizing the market value of assets. And in 2004, which wasn’t due to good investments. Was the Illinois state legislature particularly virtuous that year?

No.

That was the year of the fake contribution called a pension obligation bond. All it did was add another liability to the Illinois balance sheet. It was a balance transfer from the pensions to bondholders, and we know how dangerous that is for bondholders.

Investment performance and under-contributions are the main causes of unfunded liability growth

The largest portion of the final column, wherein the liability is more than $130 billion, is black — meaning that employer undercontributions have been the largest cumulative contributor to the current unfunded liability. I apologize for omitting the label of amount [it’s because I wanted the labels of the series to the right, and couldn’t double up]. For FY2018, the cumulative effect of employer undercontributions was $58 billion, out of the total $134 billion unfunded liability.

But wait — what about investments? Indeed, if we look at that portion, one up from the bottom, it doesn’t look that bad compared to the undercontributions…. but you need to look at the portion up top that represents changes in actuarial assumptions.

Those changes, starting around 2010, have almost all been decreasing the assumed return on assets.

If you add the change in actuarial assumptions to the investments experience… it’s still smaller than the undercontribution effects.

Let’s look at percentage contributions.

Undercontributions have grown to about 43% of the whole unfunded liability. Investment results + changes in actuarial assumptions led to 31% of the unfunded liability, so still substantial.

By the way, these graphs do differ a little from what I had done before in 2015 and 2017, as some of the effects of “benefit increases” came undone with the Illinois Supreme Court ruling. I noticed some earlier numbers moved as a result.

Underfunding pensions is a matter of choice

The Illinois state legislature chose to underfund the state pensions for decades. In every single year, going back to 1984, there was deliberate underpayment.

If I back out the impact of the 2004 pension obligation bond, the undercontribution history would look even worse than it does now.

And it’s still really bad, even as I do keep the POB in.

The pension obligation bonds did nothing for the pensions, other than to buy a little time by making the financial condition of the funds look marginally better while the overall state finances got worse.

Unfortunately for everybody involved in Illinois, it does not much matter the source of the unfunded liability at this time to fix the problem going forward. I could say it does matter with respect to whether various federal-level politicians are interested in giving Illinois extra money this year.

The only thing to note is that it’s mainly the result of deliberate choices on the part of elected officials, many of whom were elected with public union support to keep the gravy train going, and not just some bad investment results or too-high expectations of investment results (though that’s the number two reason).

If the state had required fully-funding the pensions all these years, even with too-high investment expectations, they probably would have been able to weather some of the resulting unfunded liability (and would not have escalated benefits, if they knew they had to pay for the increases in full).

The dream of Illinois pension reform

Many states are hurting right now, in terms of tax revenue, and putting money in the pensions is not going to be high on the priority list for 2020. Even with asset losses, most state pension funds should be okay.

However, by fiscal year 2018, the Illinois state funds as a group were only 40% funded, and have been bobbing at that level for years. This is a pretty bad position to be in going into a crisis. They don’t have much room to work with.

As I wrote yesterday, I don’t have a huge amount of hope that Illinois will all of a sudden become fiscally responsible. They have never had the practice. In the middle of a crisis is a hell of a time to try to learn.

Even with 40% funded pensions shading into something worse, there are several years’ worth of assets in the funds. They will not run out this year, or even next year [unless Illinois politicians do something especially wacky]. There is some time to retrench, but at such an unfunded level with really little hope of digging out… it won’t take state bankruptcy to retrench state finances, but it will definitely take amending the state constitution to get into a sustainable situation.

Pritzker is already opening up that amendment process to try to get a progressive income tax [currently barred by the Illinois state constitution].

Why not try removing that pension clause?

It doesn’t really “protect” the pensions, as it doesn’t call the money to pay pensions into being. Illinois pensions could be more sustainable if at least some adjustments could be made for current participants, because that’s what this unfunded liability covers. “Fixing” it for future participants isn’t in this graph at all — it’s only for those people who have accrued benefits. It’s for current workers, for retirees, for surviving beneficiaries, for those vested but not yet retired.

Just think about being able to stop constant 3% COLAs and minimally raise retiree healthcare co-pays. That wouldn’t be enough to fill the hole, but being able to adjust items would make the system more robust.

What a dream.

Related Posts

PSERS Update: What if it's just sloppy processes?

South Carolina Pensions: Investment Returns Recalc

Dallas Police and Fire Pensions: Pulling into the Abyss