Joe Biden's Pick for COVID Team: Zeke Emanuel -- a Hint for Public Finance Policy?

by meep

While Trump continues to sue to try to stop the veritable locomotive chugging toward Joe Biden’s inauguration, Biden’s staff announced a COVID task force:

As expected, the board’s three co-chairs are Marcella Nunez-Smith, a Yale physician and researcher; Vivek Murthy, a former U.S. surgeon general; and David Kessler, a former FDA commissioner.

Other appointees include well-known public health officials such as Julie Morita, a former Chicago health commissioner, and Eric Goosby, the founding director of the federal government’s Ryan White HIV/AIDS program.

The task force also includes a variety of other well-known doctors and academics, among them Zeke Emanuel, a former Obama administration health care adviser, and Celine Gounder, a physician and medical journalist with years of experience combating HIV and tuberculosis outbreaks.

The bolded name stirred a memory: the brother of ex-mayor of Chicago Rahm Emanuel and of super-agent Ari Emanuel, Zeke Emanuel, Aka Dr. Death or “Let them die at 75”.

Planning to shove Biden out of the way?

From Jon Gabriel at Ricochet: Biden’s COVID Task Force Includes Doctor who Wishes Biden Died 2 Years Ago

Joe Biden introduced his coronavirus task force Monday morning. It will include Dr. Ezekiel Emanuel, the “medical ethicist” who created Obamacare’s “death panels.” Curiously, Emanuel wishes the 77-year-old Biden had died two years ago.

To be fair, Dr. Emanuel only wished for his own death at age 75. Well, that’s what the headline said… and then you dig into what he actually wrote.

From 2014 in the Atlantic, Zeke Emanuel wrote: Why I Hope to Die at 75

But here is a simple truth that many of us seem to resist: living too long is also a loss. It renders many of us, if not disabled, then faltering and declining, a state that may not be worse than death but is nonetheless deprived. It robs us of our creativity and ability to contribute to work, society, the world. It transforms how people experience us, relate to us, and, most important, remember us. We are no longer remembered as vibrant and engaged but as feeble, ineffectual, even pathetic.

Um. Hmmm.

Does anybody want to tell Biden about that?

I will get back to that attitude at the end of this piece, but let me point out a couple of relevancies for COVID policy, and then broader public policy.

COVID mortality and age

From October 1, I graphed out the then-best-estimate for COVID infection fatality rate by age:

So yay, regular mortality is higher than the infection fatality rate…. but now you can see where the idea of having double our usual mortality came from. For the oldest people, the infection fatality rate is very close to their normal mortality from all causes. If COVID’s effect is additive, then you’ve almost doubled the mortality for one year …. IF everybody gets infected with the disease and IF the IFR holds constant.

What we’ve actually found is about 10% extra mortality in 2020, but unsurprisingly, we’re seeing is that most of the mortality is among the oldest people:

Boy, it will really simplify COVID policy if you decide simply not to treat those over age 75.

Would be a lot cheaper, too.

COVID mortality and nursing homes

Back in June, I pointed out a connection between COVID, nursing homes, and public finance:

I haven’t written about it much, but a very large percentage of U.S. COVID deaths were in nursing homes. (And, of course, the official numbers are suspect.)

To be nasty about it, a large amount of Medicaid funds are spent on nursing homes. By count, Medicaid covers more than 60% of nursing home residents. It costs nothing in Medicaid funds if said nursing home residents die.

People were asking me how much COVID deaths would improve funding ratios for public pensions (my quick answer: the mortality is really not high enough. Yet.)

But they didn’t ask how much Medicaid costs would be lessened by these deaths. That’s not really my area, to be sure, but it will be interesting to see the results coming out of this. New York has very high Medicaid costs, and my very cynical mind goes to that is why Cuomo forced nursing homes to take positive COVID patients. By the time Cuomo forced nursing homes to take COVID positive folks, there had been plenty of experience in Europe to show that was a bad idea… unless your goal was to kill off a bunch of old people who are expensive to keep alive.

While Dr. Emanuel’s argument for reducing life-extending/-saving treatment for the elderly is mostly that it doesn’t do much good, and besides, do you want to seem like a pathetic, burnt-out shell of your former self…. it can be that this is a signal of a major goal of a Biden administration with respect to Medicare/Medicaid: reduce spending money on elderly folks’ healthcare, so that we can use all the money for more fun stuff for younger folks! Like UBI! Video games for everybody!

Old people are expensive for the government

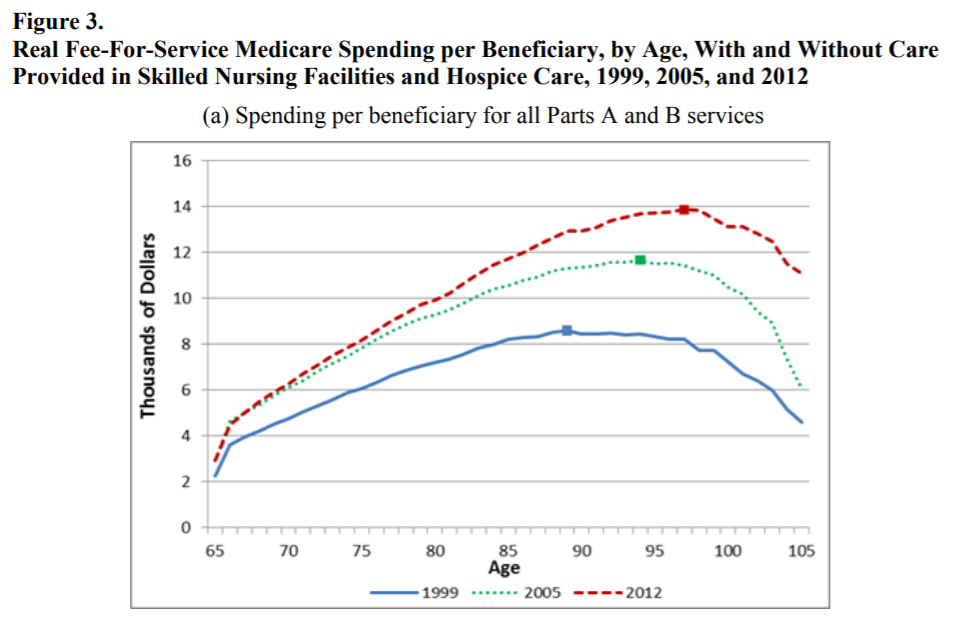

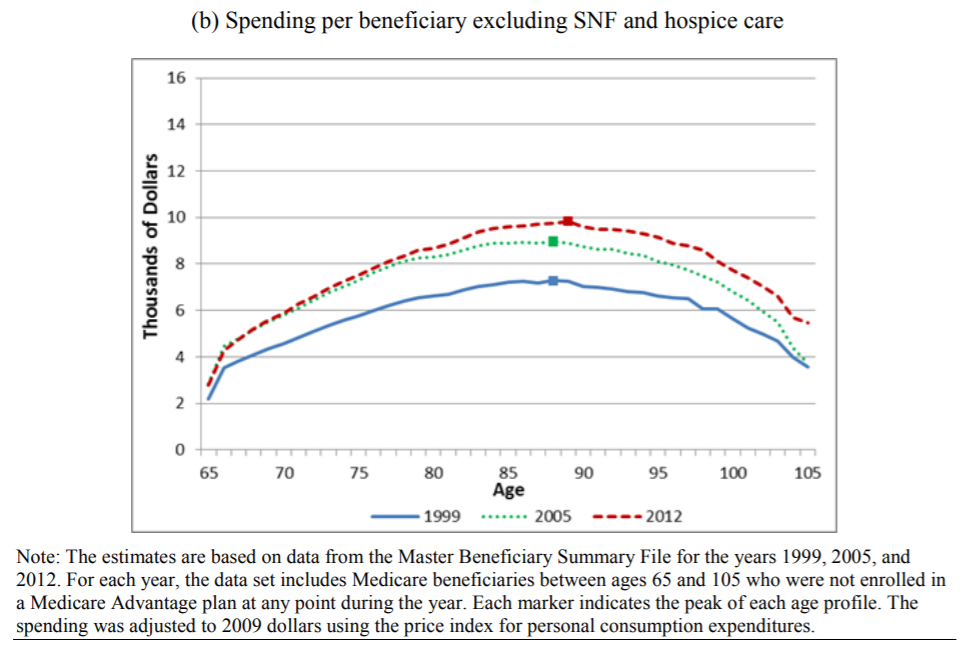

The younger elderly are not so expensive for Medicare/Medicaid — showing the trend from a 2015-2016 CBO report:

Total Medicare spending (per beneficiary), inflation-adjusted:

Medicare per beneficiary spending excluding nursing homes and hospice:

That’s not even including Medicaid expenditure, which covers a lot of nursing home residents.

But you see that the argument about convincing older people to stop using so much healthcare, and just let yourselves die, has a very different meaning when it’s somebody involved in public policy where most of the resources are used up by the oldest people.

Dead people also don’t get pensions

Back in 2014, I pointed out some ancillary benefits to Dr. Death’s attitude for people like, oh, the mayor of Chicago:

After all, public pensions are a huge problem for Chicago. Maybe Rahm is tempted to do a Daley and stick in office — Richard J. Daley was mayor of Chicago for 21 years and son Richard M. Daley was mayor for 22 years (had to stick it out to beat dad, didn’t ya).

If so, then Chicago pensions are a problem Rahm has absolutely got to deal with in a long-term way. If public pension retirees died at age 75, as opposed to ten years later (which is closer to the “real” life expectancy of retirees, as opposed to life expectancy from birth – but more on that in a later piece), a lot of the public pension problem would be solved.

Here everybody has been thinking about trying to convince retirees and judges to allow the cutting of the dollar value of monthly pension benefits, but here’s something sneakier: convince the people to die earlier. I’d have to do a calculation, but I imagine your retiree population dropping like flies ten years earlier than expected would really give pensions a boost.

We’ll know that Zeke has been trying to help his brother if the followup on this piece is why 70-year-olds should take up BASE jumping or to buy a motorcycle to tool around Chicago.

If you go back to that piece, you’ll also see I pivot to Ruth Bader Ginsberg… and we know how that one turned out.

But also Rahm Emanuel is no longer mayor of Chicago. While it wasn’t the running-out-of-fun-money that ran him off, if there had been any fun money to play with, with the lessening of public pension pressure, he might have fought on to stick around. As it is, Lori Lightfoot has the hot potato of Chicago now.

Life expectancy into old age

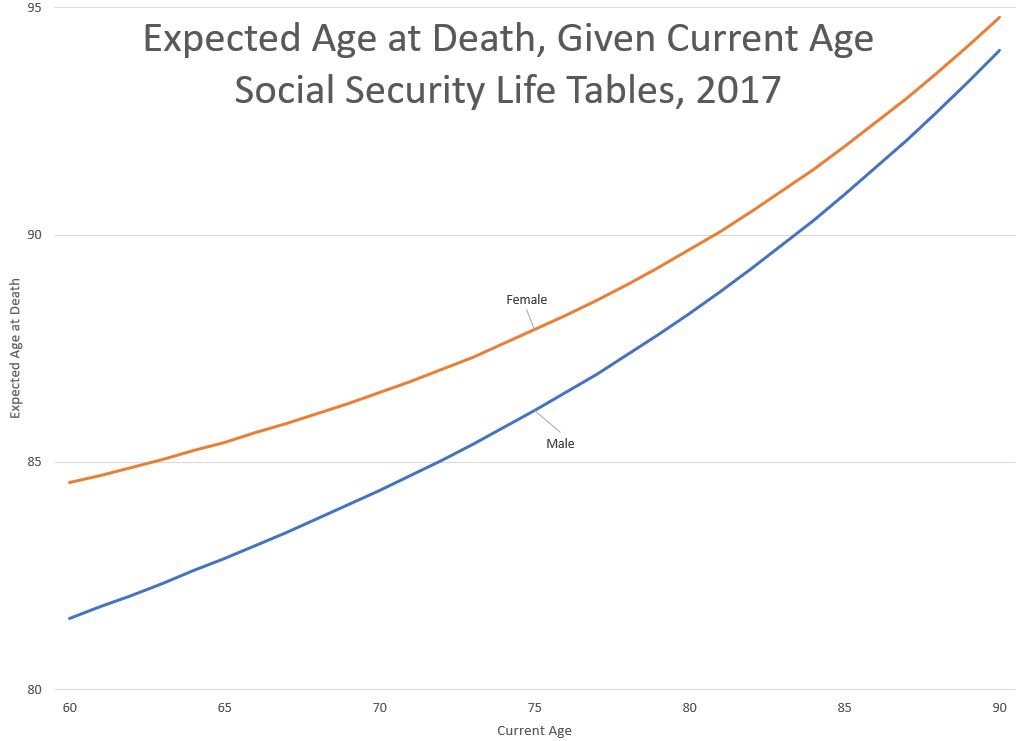

Just using current Social Security life tables, which is for calendar year 2017, we can see the following life expectancies from age (rounded):

65: 17.9 years for men, 20.5 years for women

70: 14.4, 16.5

75: 11.1, 12.9

80: 8.3, 9.7

85: 5.9, 7.0

Here’s a graph with it changed to expected age at death:

At age 75, the expectation, even for men, is for living more than a decade longer. And no, it’s not because we’re giving old people a bunch of futile medicine.

The lie about longer life in Dr. Death’s preferred policy

Back to the 2014 Atlantic piece by Dr. Emanuel:

Once I have lived to 75, my approach to my health care will completely change. I won’t actively end my life. But I won’t try to prolong it, either. Today, when the doctor recommends a test or treatment, especially one that will extend our lives, it becomes incumbent upon us to give a good reason why we don’t want it. The momentum of medicine and family means we will almost invariably get it…

There’s nothing wrong in Dr. Emanuel refusing medical care. That’s a personal choice.

But let’s look at his argument, such as it is, beyond the emotions involved:

What are those reasons? Let’s begin with demography. We are growing old, and our older years are not of high quality. Since the mid-19th century, Americans have been living longer. In 1900, the life expectancy of an average American at birth was approximately 47 years. By 1930, it was 59.7; by 1960, 69.7; by 1990, 75.4. Today, a newborn can expect to live about 79 years. (On average, women live longer than men. In the United States, the gap is about five years. According to the National Vital Statistics Report, life expectancy for American males born in 2011 is 76.3, and for females it is 81.1.)

Yes, we’re living longer.

But we’re also actually living healthier longer — that’s a huge driver of the increased life expectancy.

Since 1960, however, increases in longevity have been achieved mainly by extending the lives of people over 60. Rather than saving more young people, we are stretching out old age.

Except we’re actually pushing old age back — not merely that we’re extending life, but we’re doing something called “morbidity compression”.

Compression of morbidity is a reduction over time in the total lifetime days of chronic disability, reflecting a balance between (1) morbidity incidence rates and (2) case-continuance rates—generated by case-fatality and case-recovery rates. Chronic disability includes limitations in activities of daily living and cognitive impairment, which can be covered by long-term care insurance.

Morbidity improvement can lead to a compression of morbidity if the reductions in age-specific prevalence rates are sufficiently large to overcome the increases in lifetime disability due to concurrent mortality improvements and progressively higher disability prevalence rates with increasing age.

…..

The major findings of the empirical analyses are the substantial slowdowns in the degree of mortality compression over the past half century and the unexpectedly large degree of morbidity compression that occurred over the morbidity/disability study period 1984–2004; evidence from other published sources suggests that morbidity compression may be continuing.

To put this into simple terms: not only are people in the U.S. living to older ages, but they’re living without the disabilities of old age for longer as well. Morbidity compression has to do with people remaining heavily disabled from age-related problems for shorter periods of time.

An article with less academic terminology from the same author, “New Perspectives on the

Compression of Morbidity and Mortality” by Eric Stallard in the March/April 2014 issue of Contingencies:

THE DYNAMICS OF MORBIDITY AND MORTALITY are central concerns in actuarial practice, having major implications for life, health, pension, and long-term care (LTC) insurers; for Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security programs; for public policy planners; and for career and retirement planning among the general public.

…..

These results jointly imply that very substantial amounts of morbidity compression occurred during a period in which there was little if any mortality compression. This finding indicates that the two processes are not closely tied: Morbidity compression does not require concurrent mortality compression.

Mortality compression is something that primarily actuaries think about — it has to do with how “bunched up” the distribution at age of death is. There had been disputes as to whether age at death was being pushed out meaningfully (yes), or merely getting “squared” (also, somewhat, but less than we thought).

Morbidity compression is something that has gotten short shrift, and people’s “gut” instincts on this have been very wrong, mainly because they don’t notice when people are doing well…. they notice when it all falls apart.

Here is the point: in many ways, we’ve actually gotten better health outcomes for the elderly than we’ve been able to extend life. Most of the “life extension” we’ve seen is at older ages, and a lot of the extension is actually from keeping people well longer.

The attitude in “let the old folks die”

But the nastiest part of Emanuel’s piece is the attitude: once you are disabled, physically or mentally, life is no longer worth living.

My favorite pro-life group is Not Dead Yet, which describes itself as:

Not Dead Yet is a national, grassroots disability rights group that opposes legalization of assisted suicide and euthanasia as deadly forms of discrimination against old, ill and disabled people. Not Dead Yet helps organize and articulate opposition to these practices based on secular social justice arguments. Not Dead Yet demands the equal protection of the law for the targets of so called “mercy killing” whose lives are seen as worth-less.

They are explicitly fighting against active measures to kill “useless eaters”, and they also oppose measures that remove normal care for them:

Health Care Cuts Severe

For seniors and people with disabilities who depend on publicly funded health care, federal and state budget cuts pose a very large threat. Many people with significant disabilities, including seniors, are being cut from Medicaid programs that provide basic help to get out of bed, use the toilet and bathe.

Involuntary Denial of Care

Most people are shocked to learn that futility policies and statutes allow health care providers to overrule the patient, their chosen surrogate or their advance directive and withhold desired life-sustaining treatment. With the cause of death listed as the individual’s medical conditions, these practices are occurring without meaningful data collection, under the public radar.

It is but a short step from saying the elderly shouldn’t get life-extending care because their lives suck to saying the physically and mentally disabled shouldn’t get medical care because their lives suck.

Potential public finance policy for the Biden administration

This is the problem when government’s function is seen primarily as the distribution of goodies: some people will be considered “cost sinks” and other people will be “net revenue sources”.

(I’ve been in a company where my department was considered overhead. That’s not a good feeling. You’ve always got a target on your back.)

It’s one thing if the government temporarily gives one goodies, but then you go back to being a nice little revenue source, there’s a good taxpayer.

But once people become elderly, especially if they’re no longer a dependable source of votes, they’re cost sinks and how the hell are you to have all your pie-in-the-sky programs if these people just keep sucking up money!

In particular, all sorts of old age programs — Social Security, Medicare, nursing home care in Medicaid, public pensions — have been sucking more and more cash out of government budgets, especially as the pig-in-a-python demographic bulge of Boomers have aged, with the oldest Boomers, born in 1946, having reached age 65 in 2011.

That oldest cohort of Boomers will turn 75 in 2021.

Does anybody want to tell them that the plan to deal with their escalating costs is just to let them die?

Some may say “Oh, Zeke Emanuel is just one among many on the task force, he’s not even a co-chair”, but you need to know that he has two specialties in medicine, one being breast oncology… which has zero relevance for COVID. His other specialty relates to these sorts of cost-benefit analyses of who gets treated and who doesn’t…and this was specifically in his 2014 piece:

What about simple stuff? Flu shots are out. Certainly if there were to be a flu pandemic, a younger person who has yet to live a complete life ought to get the vaccine or any antiviral drugs. A big challenge is antibiotics for pneumonia or skin and urinary infections. Antibiotics are cheap and largely effective in curing infections. It is really hard for us to say no. Indeed, even people who are sure they don’t want life-extending treatments find it hard to refuse antibiotics. But, as Osler reminds us, unlike the decays associated with chronic conditions, death from these infections is quick and relatively painless. So, no to antibiotics.

This seems pretty damn relevant.

Both antibiotics and flu shots are very simple interventions. They’re not expensive. And here he is, saying that those over age 75 shouldn’t take them… and he even considered the case of a flu pandemic (which we had in 2009, in case you forgot.)

And I am not advocating 75 as the official statistic of a complete, good life in order to save resources, ration health care, or address public-policy issues arising from the increases in life expectancy. What I am trying to do is delineate my views for a good life and make my friends and others think about how they want to live as they grow older. I want them to think of an alternative to succumbing to that slow constriction of activities and aspirations imperceptibly imposed by aging. Are we to embrace the “American immortal” or my “75 and no more” view?

Are we to embrace “You can’t do what you used to be able to do at age 30, so just stop sucking up resources, you useless eater?”

And no, I’m not putting words into his mouth. This is putrid:

But 75 defines a clear point in time: for me, 2032. It removes the fuzziness of trying to live as long as possible. Its specificity forces us to think about the end of our lives and engage with the deepest existential questions and ponder what we want to leave our children and grandchildren, our community, our fellow Americans, the world. The deadline also forces each of us to ask whether our consumption is worth our contribution.

Seriously, that’s evil. Yes, utilitarians out there, I consider your viewpoint evil. I do not consider human life valuable simply from people’s economic contributions or how “useful” they are.

Dr. Death got a lot of pushback in 2014, but it seems particularly relevant that a man whose attitude is “the elderly should just die” is on Biden’s COVID task force. I am doubtful that Emanuel will get booted (nor the staffer who picked him), and I am doubtful that the mainstream media will probe this at all, at least, not until Trump is safely gone from office.

If that’s going to be the attitude of the Biden administration toward public policy, it would be a good idea for the public to find out.

It would have been even better to have found out before the election, but eh. Whaddya gonna do? Actually ask hard questions of a Democratic politician?

Related Posts

Happy Bobby Bonilla Day for 2022!

Have an Actuarial New Year! A few Actuarial Gifts and Recommendations

Interest Rates and Sumo, Nagoya 2022 Edition