Weekend Book: A Dickensian Curiousity

by meep

I write, of course, of The Old Curiosity Shop, and unlike my prior two weekend books, I can’t recommend it without qualification.

Mind you, there are some very good bits in it — after all, it’s still Dickens. But there is a reason it’s not as much read as Great Expectations or A Tale of Two Cities… and it’s not only because of length. (Of course, the shortest Dickens – A Christmas Carol – is the most read.)

What The Old Curiosity Shop is best known for, of course, is the death of Little Nell [and if you think I’m going to put spoiler alerts on books that are over 100 years old… yeah. The surprises in Dickens are the least of Dickens, in my opinion.) Just stealing outright from my post on childhood deaths I will repeat a few items:

Nell actually dies “off stage”, and there is an entire maudlin bit where her grandfather doesn’t realize that she’s been dead and he keeps going on about her sleeping. Part of Oscar Wilde’s famous quote on the death of Little Nell:

One must have a heart of stone to read the death of little Nell without laughing.

It is a ridiculous scene, primarily because it WILL NOT STOP. I pretty much skipped through that bit. You do realize Nell is dead before the very end of the scene. I will grab the Wikipedia explanation of the critical reaction:

Of a similar opinion was the poet Algernon Swinburne, who called Nell “a monster as inhuman as a baby with two heads.”6

The Irish leader Daniel O’Connell famously burst into tears at the finale, and threw the book out of the window of the train in which he was travelling.7

The hype surrounding the conclusion of the series was unprecedented; Dickens fans were reported to have stormed the piers in New York City, shouting to arriving sailors (who might have already read the final chapters in the United Kingdom), “Is Little Nell alive?” In 2007, many newspapers claimed that the excitement at the release of the last instalment of The Old Curiosity Shop was the only historical comparison that could be made to the excitement at the release of the last Harry Potter novel, Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows.8

The Norwegian author Ingeborg Refling Hagen is said to have buried a copy of the book in her youth, stating that nobody deserved to read about Nell, because nobody would ever understand her pain. She compared herself to Nell, because of her own miserable situation at the time.

This is all a bit much.

Anyway, it is the common jerk Dickens move — he abuses one of his fictional children in the novel, holds out the hope of a happy ending, and then NOPE! DEAD KID!

For a related reason, the only Dickens novel I have read only once and have determined never to read again is Oliver Twist. Oliver does get his happy ending, but only after having been tossed between so many nasty situations… and there’s nothing in the rest of the novel that makes up for the fictional child abuse.

There is something in Old Curiosity Shop, though: Quilp.

I’m going to steal from myself again without bothering to put it in quotes. Quilp is simply the most entertaining of all the Dickensian villains, and has the most satisfying death.

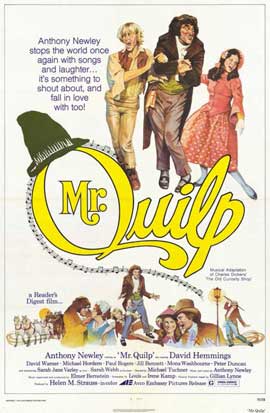

Mr. Quilp is, essentially, an evil dwarf with a gusto for being an evil dwarf. He’s not unlike Shakespeare’s Richard III in many ways. I’ve not actually seen any movies or plays of this novel, but I came across this:

It looks like Anthony Newley played Quilp as a Richard III-like hunchback. Looking at the IMDB page, the shortest man to play Quilp in a movie thus far was 5’5” (my own height…I am not a dwarf.) Not only are most of the actors not short enough, they’re generally not ugly enough. Peter Dinklage would make an awesome Quilp. He’s too good-looking, but makeup can work wonders.

I have Dickens characters I enjoy more than Quilp, but as villains go, he’s the most enjoyable.

Yes, he is violent, but it’s hard to take violence from him seriously — he’s so small and isn’t really all that strong (a point on which later). But he is extremely intimidating to those around him. His cruelty is more of the psychological sort.

Early on in the novel, Quilp catches his wife having a hen party (orchestrated by his mother-in-law) to bitch about Quilp himself. Mrs. Quilp is not joining in on the criticism, though. She does, for some reason, actually love Quilp. Just the normal perversity of human nature, I guess. Quilp comes in unexpectedly and is found to have overheard the bitch session. He has a nice retort to his mother-in-law (who lives with the Quilps):

‘Why an’t you of your mother’s way of thinking, my dear?’ said the dwarf, turing round and addressing his wife, ‘why don’t you always imitate your mother, my dear? She’s the ornament of her sex—your father said so every day of his life. I am sure he did.’

‘Her father was a blessed creetur, Quilp, and worthy twenty thousand of some people,’ said Mrs Jiniwin; ‘twenty hundred million thousand.’

‘I should like to have known him,’ remarked the dwarf. ‘I dare say he was a blessed creature then; but I’m sure he is now. It was a happy release. I believe he had suffered a long time?’

The old lady gave a gasp, but nothing came of it; Quilp resumed, with the same malice in his eye and the same sarcastic politeness on his tongue.

Heh. By the way, after this, Mrs. Jiniwin, the mother-in-law, retires, and then Mr. Quilp tortures his wife by making her sit up all night with him, silently, while he smokes. Mrs. Quilp is terrified of him, though the worst he does physically is pinch her so hard to create bruises — his cruelty is mental, and he fills her with guilt over her part in determining that Nell’s grandfather is not actually rich but is taking the money Quilp has loaned him and gambling with it.

At the end of the novel Quilp abandons his wife to live at his warehouse down by the wharf, after he had an long, unexplained absence during which it is assumed that Quilp has died. Like with the bitch party, Quilp comes upon Mrs. Quilp, Mrs. Jiniwin, and a few others discussing having Quilp officially declared dead. Quilp goes to the warehouse as a partial revenge on Mrs. Quilp. Mrs. Quilp is agitated by this abandonment and tries to convince him to stay, but nothing doing. She comes to the warehouse to deliver a letter to him.

‘I have brought a letter,’ cried the meek little woman.

‘Toss it in at the window here, and go your ways,’ said Quilp, interrupting her, ‘or I’ll come out and scratch you.’

‘No, but please, Quilp—do hear me speak,’ urged his submissive wife, in tears. ‘Please do!’

‘Speak then,’ growled the dwarf with a malicious grin. ‘Be quick and short about it. Speak, will you?’

‘It was left at our house this afternoon,’ said Mrs Quilp, trembling, ‘by a boy who said he didn’t know from whom it came, but that it was given to him to leave, and that he was told to say it must be brought on to you directly, for it was of the very greatest consequence.—But please,’ she added, as her husband stretched out his hand for it, ‘please let me in. You don’t know how wet and cold I am, or how many times I have lost my way in coming here through this thick fog. Let me dry myself at the fire for five minutes. I’ll go away directly you tell me to, Quilp. Upon my word I will.’

Her amiable husband hesitated for a few moments; but, bethinking himself that the letter might require some answer, of which she could be the bearer, closed the window, opened the door, and bade her enter. Mrs Quilp obeyed right willingly, and, kneeling down before the fire to warm her hands, delivered into his a little packet.

‘I’m glad you’re wet,’ said Quilp, snatching it, and squinting at her. ‘I’m glad you’re cold. I’m glad you lost your way. I’m glad your eyes are red with crying. It does my heart good to see your little nose so pinched and frosty.’

‘Oh Quilp!’ sobbed his wife. ‘How cruel it is of you!’

‘Did she think I was dead?’ said Quilp, wrinkling his face into a most extraordinary series of grimaces. ‘Did she think she was going to have all the money, and to marry somebody she liked? Ha ha ha! Did she?’

To jump to the end: yes, she gets all the money, marries someone much nicer to her, and her new husband makes her mother go live somewhere else. So don’t worry for Mrs. Quilp. She’ll be just fine.

But not Quilp.

In the letter is a warning from one of Quilp’s confederates, Sally Brass, that the law would soon be upon him because her brother has turned king’s evidence, as it were. Quilp must get away before he is found and imprisoned.

It’s an exceedingly foggy day and somebody is banging on his gate. Obviously, Quilp will not let them in. He makes preparations while muttering threats against those who betrayed his nefarious plans. He makes to leave in the dark of night….but this is a dangerous thing, as well he should know. His wharf is set up specifically to thwart intruders.

It also leads to his death. (Note how his lack of actual physical strength plays into his death)

At that moment the knocking ceased. It was about eight o’clock; but the dead of the darkest night would have been as noon-day in comparison with the thick cloud which then rested upon the earth, and shrouded everything from view. He darted forward for a few paces, as if into the mouth of some dim, yawning cavern; then, thinking he had gone wrong, changed the direction of his steps; then stood still, not knowing where to turn.

‘If they would knock again,’ said Quilp, trying to peer into the gloom by which he was surrounded, ‘the sound might guide me! Come! Batter the gate once more!’

He stood listening intently, but the noise was not renewed. Nothing was to be heard in that deserted place, but, at intervals, the distant barkings of dogs. The sound was far away—now in one quarter, now answered in another—nor was it any guide, for it often came from shipboard, as he knew.

‘If I could find a wall or fence,’ said the dwarf, stretching out his arms, and walking slowly on, ‘I should know which way to turn. A good, black, devil’s night this, to have my dear friend here! If I had but that wish, it might, for anything I cared, never be day again.’

As the word passed his lips, he staggered and fell—and next moment was fighting with the cold dark water!

For all its bubbling up and rushing in his ears, he could hear the knocking at the gate again—could hear a shout that followed it—could recognise the voice. For all his struggling and plashing, he could understand that they had lost their way, and had wandered back to the point from which they started; that they were all but looking on, while he was drowned; that they were close at hand, but could not make an effort to save him; that he himself had shut and barred them out. He answered the shout—with a yell, which seemed to make the hundred fires that danced before his eyes tremble and flicker, as if a gust of wind had stirred them. It was of no avail. The strong tide filled his throat, and bore him on, upon its rapid current.

Another mortal struggle, and he was up again, beating the water with his hands, and looking out, with wild and glaring eyes that showed him some black object he was drifting close upon. The hull of a ship! He could touch its smooth and slippery surface with his hand. One loud cry, now—but the resistless water bore him down before he could give it utterance, and, driving him under it, carried away a corpse.

It toyed and sported with its ghastly freight, now bruising it against the slimy piles, now hiding it in mud or long rank grass, now dragging it heavily over rough stones and gravel, now feigning to yield it to its own element, and in the same action luring it away, until, tired of the ugly plaything, it flung it on a swamp—a dismal place where pirates had swung in chains through many a wintry night—and left it there to bleach.

And there it lay alone. The sky was red with flame, and the water that bore it there had been tinged with the sullen light as it flowed along. The place the deserted carcass had left so recently, a living man, was now a blazing ruin. There was something of the glare upon its face. The hair, stirred by the damp breeze, played in a kind of mockery of death—such a mockery as the dead man himself would have delighted in when alive—about its head, and its dress fluttered idly in the night wind.

Best ever. I also like some other Dickensian villain deaths — Bradley Headstone & Rogue Riderhood for pure drama is my favorite, but for laugh-out-loud enjoyment, Quilp’s death beats Anna Karenina throwing herself in front of a train or Kate Chopin’s tiresome “heroine” walking into the sea. Better even than Madame Lafarge being killed by Miss Pross (which was definitely a kickass moment for Pross, but still a bit of a mess).

The man is killed by his own security measures.

MWA HA HA HA

I love it.

So yes, Nell and her grandfather are just tiresome, especially when Nell just “happens” to take a nap in every damn church or churchyard (aka cemetery) she passes by.

But I re-read the book each time for Quilp, and especially his death. Now there’s some narrative satisfaction.

Related Posts

Weekend books: Lost in Language - quick review, and my search for new voices

Weekend Book: Who Doesn't Love a Good Murder?

Meep on Books: Some Catch-Up with Videos