Dataviz: Wall Street Bonuses (Watch Out for Falling Tax Revenues, NY)

by meep

I see from the NYTimes that Wall Street bonuses have been down:

Wall Street Bonuses Fell in 2015, and 2016 Isn’t Looking Rosy

Wall Street bonuses are down for the second straight year, and recent market volatility and cutbacks suggest that 2016 is shaping up to be a difficult year, according to the New York State comptroller.

The average bonus paid in the securities industry fell 9 percent, to $146,200, last year, while the bonus pool for employees who work in New York City shrank 6 percent, to $25 billion.

The finance industry is a crucial component of the state’s annual tax revenue, contributing about 17.5 percent of the total last year. Wall Street’s health reverberates throughout the city and state economies; profits are on the line for luxury retailers, restaurants, real estate firms and even auto dealers.

Already New York State has cut its forecast for this year’s bonus pool for finance and insurance jobs in the state, now predicting a 2.5 percent drop.

Securities industry profit fell 10.5 percent last year, to $14.3 billion, the lowest since 2011.

…..

Mr. DiNapoli has released the numbers each year as lawmakers in the state capital take up budgeting for the next fiscal year. For every job on Wall Street, two are created elsewhere in the economy, according to the comptroller’s office. The average salary, including bonuses, for securities industry employees in New York City rose 14 percent in 2014 to $404,800, which is a record. Data for 2015 is not yet available.

Here is the most recent press release from the Office of the NY State Comptroller:

Wall Street Bonuses and Profits Decline in 2015

The average bonus paid in New York City’s security industry declined by 9 percent to $146,200 in 2015 as industry-wide profits declined by 10.5 percent, according to an estimate released today by New York State Comptroller Thomas P. DiNapoli.

“Wall Street bonuses and profits fell in 2015, reflecting a challenging year in the financial markets,” DiNapoli said. “While the cost of legal settlements appears to be easing, ongoing weaknesses in the global economy and market volatility may dampen profits in 2016. Both the state and city budgets depend heavily on the securities industry and lower profits could mean fewer industry jobs and less tax revenue.”

The securities industry reported that pre-tax profits for the broker/dealer operations of New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) member firms—the traditional measure of industry profitability—declined by nearly $1.7 billion to $14.3 billion in 2015. After a strong first half and a solid third quarter, the industry reported a small loss of $177 million in the fourth quarter, the first quarterly loss since 2011.

Even though expenses were lower in 2015, profits declined because revenues were weak, particularly from trading and underwriting. Profits declined for the third consecutive year, reaching the lowest reported level since 2011.

Although industry-wide profits were down, employment in the securities industry in New York City grew by 2.7 percent in 2015, averaging 172,400 jobs for the year. The industry added 4,500 jobs, compared with 2,400 jobs added in 2014. This marks the first time since the financial crisis that the industry in New York City has added jobs for two years in a row. Despite the job gains, the industry is still 8 percent smaller than before the financial crisis.

And the Comptroller very nicely made some of his own graphs available.

STATE-PROVIDED GRAPHS

Obviously in nominal dollars, not inflation-adjusted.

Securities industry profits (click through to see the graph. I find it boring.)

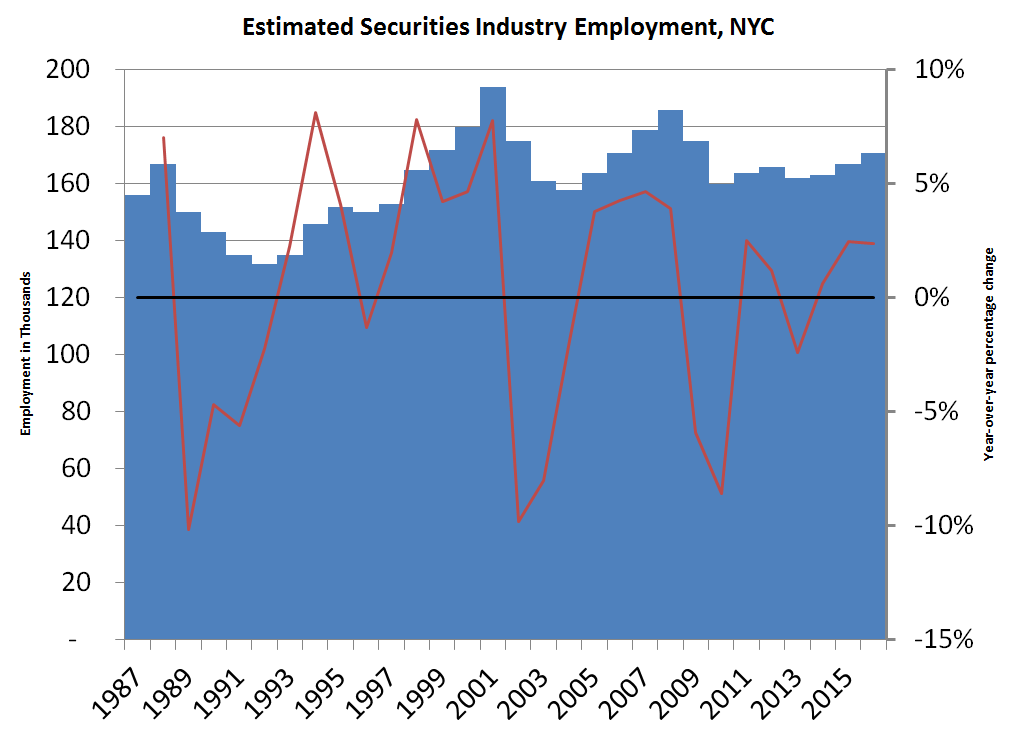

Securities industry employment in NYC, which is for a shorter period than the two graphs linked above.

MEEP-PROVIDED GRAPHS

Thing is, if I want to think about potential revenue to the NY exchequer, I’m going to care not about the average bonus, but the total amount of bonuses received.

Luckily, the Comptroller gives us the data, but no graphs.

I used that info, plus CPI-U, to estimate employment and an inflation-adjusted bonus pool.

First, the employment:

Note: the red line shows the year-over-year percentage change. A little frothy there, but not overly so. We see employment fluctuating between -10% post-bust and 8% for peak growth years.

Now, the bonus pool:

Those are billions of $, inflation-adjusted to 2015 amounts. That’s quite a bit frothier than the employment numbers. That wildly fluctuates, in fact.

WHY DO WE CARE?

Let me go back to the press release:

Although the securities industry is smaller, it is still one of New York City’s most powerful economic engines. The industry accounted for 22 percent of all private sector wages paid in New York City in 2014 even though it accounted for less than 5 percent of the City’s private sector jobs. An estimated 1 in 9 jobs in the city are either directly or indirectly associated with the securities industry;

….

Securities-related activities are a large contributor to state and city tax revenues. DiNapoli estimates that securities-related activities accounted for 7.5 percent ($3.8 billion) of all city tax revenue in city fiscal year 2015 and 17.5 percent ($12.5 billion) of state tax collections in State Fiscal Year (SFY) 2014-15. The state also expects to receive more than $8.5 billion in settlement payments from financial firms during SFY 2014-15 and SFY 2015-16; and

Note: the state is more dependent on the financial services industry than the city itself is.

Think about that.

TOO DEPENDENT ON WALL STREET = ?

Thanks to the Empire Center’s See Through NY site, I have state taxes to graph (I am excluding other revenue than taxes for now – because that means I’d be including stuff like SUNY tuition… and I don’t want to.)

I’m going to graph the “real” taxes (projected to 2020 dollars):

And the percentage of taxes by source (doesn’t matter if it’s real or nominal):

Note: the state is becoming more dependent on personal income taxes. It started out at less than 45% of tax revenue in 1976, and ended up as more than 60% of taxes in 2016.

PRECARIOUSNESS OF DEPENDING ON RICH PEOPLE

The problem is that people in the financial biz have extremely volatile revenue streams themselves. If you’re trying to build up a steady stream of revenue for state expenditures, being dependent on a volatile source of funds is not good.

But you don’t have to take my word for it. (Or Connecticut’s experience to prove it.)

The Pew Charitable Trusts have researched this.

Why Taxing the Wealthy Can Be Trouble for States

As the gap between the rich and the poor widens, states are finding that taxing the incomes of the rich means living with unstable budgets.

That’s because wealthy Americans are more likely to have investments in the stock market. When the market falls, so do their tax payments. Stock market turmoil can hurt state pension funds, too. But while it takes years for states to feel that impact, a dip in the markets — or a lackluster Wall Street bonus season — can create an immediate fiscal crisis.

Connecticut Gov. Dannel Malloy announced budget cuts in September as the sputtering stock market lowered revenue predictions. State analysts now predict a more than $200 million deficit, and the Democratic governor is preparing to announce layoffs and program cuts. Last week, he cut payments to hospitals by $140 million.

California is bracing for lower-than-expected revenue from capital gains this year, and economists have advised New York legislators to scale back their expectations for next year (New York’s fiscal year ends this month).

I don’t know if this embedding will work. Let’s try it:

If that didn’t work, follow this link.

Going back to the report, I agree with this idea:

Lembo said that progressive structure isn’t likely to change. Instead, last year’s budget requires the state to automatically deposit revenue that exceeds estimates into a rainy day fund, beginning in 2021. (The Pew Charitable Trusts, which also funds Stateline, lobbied for the legislation and has advised lawmakers in California and Minnesota on similar reforms.)

McMahon argues that, rather than adjusting their rainy day funds, states should set aside capital gains and other volatile revenue sources for specific, one-time projects. That way they wouldn’t rely on the money to fund ongoing services.

In any case, Connecticut’s rainy day fund reform isn’t helping the state now. And the drop in estimated payments from taxpayers with irregular incomes was so sudden this quarter that Republican lawmakers say something else must be going on.

State Rep. Vincent Candelora, a supporter of the rainy day fund legislation, said he’s heard that millionaires are moving out of Connecticut to avoid the state’s high taxes, including the recently raised estate tax. “Many of our residents have homes in other states, so they’ll change residency to avoid the tax,” he said.

The Hartford Courant speculated last week that a single man’s departure to Florida (net worth: $11.1 billion) worsened the state’s deficit.

It’s nice to be progressive and all, but if one person’s residency makes or breaks the state budget: you have a problem.

You can’t count on high producers to continue to produce highly.

And just remember about the golden goose if you should happen to think about outright wealth seizure.

Related Posts

On Dreams of Bankruptcy

STUMP Podcast: Interest Rates and Sumo

State Bankruptcy and Bailout Reactions: No Bailout, Yes Bankruptcy Group