An Ugly Interest Rate Environment and Public Pensions Chasing Returns

by meep

The Federal Reserve Open Markets Committee (FOMC) had a meeting this past week, and the reactions have been ugly.

This is what I mean by ugly: a yield curve inversion.

The x-axis is years, and the y-axis is the percent rate.

What that graph shows is that the 1-month to 6-month Treasury rates, aka short-term rates, are HIGHER than the rates from 1 year to 7 years maturity.

I graphed what the yield curve looked like at the beginning of the month, so you can see what happened: the short-term rates, which the FOMC can most directly influence, stayed put. Longer term rates all dropped.

Let’s see what the curve looked like a year ago:

That curve from 2018 shows a “normal” pattern for yield curves — in general, interest rates for longer-term debt are higher than shorter term.

Let’s go to Investopedia for a reference:

An inverted yield curve is an interest rate environment in which long-term debt instruments have a lower yield than short-term debt instruments of the same credit quality. This type of yield curve is the rarest of the three main curve types and is considered to be a predictor of economic recession.

A partial inversion occurs when only some of the short-term Treasuries (five or 10 years) have higher yields than 30-year Treasuries. An inverted yield curve is sometimes referred to as a negative yield curve.

Now, the curve isn’t fully inverted (that’s NASTY) — it’s still got positive slope for the very longest term issues.

NEWS COVERAGE OF THE INVERSION

The business news is all over this, because this doesn’t happen all that often, and it affects the financial industry a great deal.

Bankrate.com: The Treasury yield curve has inverted, but that’s not the only economic indicator worth following

The inversions continue to happen in the yield curve. This Wall Street-speak means that short-term fixed-income investments like bonds are paying more interest than comparable longer-term investments, something that hasn’t happened since 2007.

The latest example is the 3-month Treasury bill (yielding 2.45 percent) slightly inverting with the 10-year Treasury (approximately 2.44 percent). Though, according to Bloomberg data they were also even for part of the morning as well.

….

When the yield curve inverts – meaning a shorter-term Treasury bill has a higher yield than a long-term Treasury – it’s predicted every recession back to the late 1960s, McBride says.Keep in mind that investors usually demand a higher rate of interest for locking up their money longer.

The first Treasury that people buy when risk increases is the 10-year Treasury, says Campbell Harvey, a professor of finance at Duke University.

“What is a safer investment than (the) 10-year Treasury? … When people start buying it, the price goes up, the yield goes down,” Harvey says. “So it’s just a great indicator in terms of kind of the perception of risk.”

…..

Why the 90-day Treasury may be a key Treasury to monitor

Harvey says he wrote his 1986 doctoral dissertation at the University of Chicago about the yield curve, focusing on the comparison between the spread between the five-year note and the 90-day Treasury bill. The latter length is key, because it equals the time in a quarter.“So, there’s always a lead time. The lead time is empirically anywhere from three quarters to six quarters,” Harvey says.

When the 90-day Treasury bill and the 5-year Treasury inverted, the clock started. If it continues for a full quarter, Harvey says that would forecast a recession beginning in 2020.

But Harvey says that the yield curve inversion isn’t the only item on his watch list. According to U.S. Department of the Treasury data, there was a five basis point spread between the 3-month Treasury bill and the 10-year Treasury yesterday.

The issue isn’t a momentary inversion, which does happen from time to time. It’s persistent inversion.

Let’s try a few more stories.

Marketwatch: Treasury yield curve inverts for first time since 2007, underlining recession worries

A closely watched measure of the Treasury yield curve inverted Friday for the first time since 2007, highlighting fears that a global slowdown will take a toll on the U.S. economy.

The yield on the 10-year Treasury note TMUBMUSD10Y, -3.13% fell nearly 11 basis points to 2.428%, pushing it below the yield on the three-month T-bill at 2.453%. An inversion of that portion of the yield curve is seen as a reliable warning of a potential recession within a year or two. Inversions have preceded every U.S. recession going back to 1955 with only one false positive, researchers at the San Francisco Federal Reserve found. While inversions of other portions of the curve have also served as recession indicators, the researchers said the 3-month/10-year measure is the most reliable.

Bond yields around the world tumbled after a raft of disappointing purchasing-managers-index readings for the eurozone affirmed fears of lackluster growth in the 19-member group already contending with a trade slowdown and Brexit uncertainty. This comes after the Federal Reserve cut back on its interest-rate projections from two to none this week, with Fed Chairman Jerome Powell citing global economic headwinds for the cautious stance. Yields tend to retreat when growth prospects sour, and inflation fears have waned.

U.S. stocks, meanwhile, accelerated losses as the yield curve inverted.

Global bond-markets rallied on Friday, sending yields lower, as a raft of weaker-than-expected eurozone data drew investors into the perceived safety of government paper. Yields fall as bond prices rise.

Bloomberg: U.S. Treasury Yield Curve Inverts for First Time Since 2007

A closely watched section of the Treasury yield curve on Friday turned negative for the first time since the crisis more than a decade ago, underscoring concern about a possible economic slump and the prospect that the Federal Reserve will have to cut interest rates.

The gap between the 3-month and 10-year yields vanished on Friday as a surge of buying pushed long-end rates sharply lower. Inversion is widely considered a reliable harbinger of recession in the U.S. The 10-year slipped to as low as 2.439 percent.

U.S. central bank policy makers on Wednesday lowered both their growth projections and their interest rate outlook, with the majority of officials now envisaging no hikes this year. That’s down from a median call of two at their December meeting. Traders took that dovish shift as their cue to dig into positions for a Fed easing cycle, pricing in a cut by the end of 2020 and a one-in-two chance of a reduction as soon as this year.

So. What does this have to do with public pensions, as I note in my headline?

It does in a fundamental way, and it doesn’t in a surface way.

PUBLIC PENSIONS AND INTEREST RATES

So, public pensions are not required to value their liabilities in the way that annuities are valued, or even private pensions.

From a financial economics standpoint, the common theory used to value all sorts of financial instruments, such as stock options and interest rate swaps, if you are making a risk-free promise, then you should use a risk-free interest rate to value that promise.

That would be closely tied to Treasury rates, in the U.S.

This sort of valuation recognizes there is a yield curve, and so, in general, cash flows that are 10 years in the future would be discounted at a 10-year rate, and cash flows only one year in the future would be discounted at a 1-year rate.

Of course, that’s not what public pensions do. It’s a bit more complicated than what I’m about to say, but they essentially base the discount rate on their expected rate of return on risky assets. That has been about 7 – 8% for most plans.

I have written about this particular subject many times as this is what set me off against public pension actuaries about a decade ago, when I was working on income annuities at TIAA.

Here are some of my posts just here at STUMP:

- Math Ain’t Magic: Playing With Numbers Doesn’t Make Pensions Cheaper

- Actuarial Standards of Practice on Pensions: ASOP 4 – a Call for Comments

- Public Pensions Primer: How Discount Rates Work

- Let’s Get Ready for an Actuarial Rumble!

- Public Pensions Primer: The Choice of Discount Rate and Return Volatility

- Public Pensions Actuarial Valuations: Point-Counterpoint-DENIED!

- Much Ado About Discount Rates: Welcome to the Pension California

- Public Pensions: Why Do 100% Required Contribution Payers Have Decreasing Fundedness?

- Dataviz: Public Pensions Assumed Rate of Return

- Public Pensions: Actuarial Assumptions and Professional Ethics

- Causes of Public Plan Insolvency: On Public Pension Valuation

I will come back to that last link in a bit, because I want to talk about what Calpers is doing.

CALPERS PILING ON THE PRIVATE EQUITY

Here are pieces just from the last week:

- CalPERS moving forward with $20 billion expansion of its private equity investments

- CalPERS Investment Committee Approves Private Equity Plan at Urging of the CIO

- Calpers goes all in on private equity

- Calpers Wants to Double Down on Private Equity

- Prominent CalPERS Beneficiaries Send Forceful, Savvy Objections to the Proposed Private Equity Scheme; Contrast With Canned Letters CalPERS Pressed Allies to Submit

That last item is from naked capitalism, and the next one is also from naked capitalism.

Memo to CalPERS: The Market Won’t Provide High Returns Just Because You Need Them

By Ben Carlson, CFA, and the the Director of Institutional Asset Management at Ritholtz Wealth Management. Originally published at A Wealth of Common Sense

The late-Peter Bernstein once wrote, “The market’s not a very accommodating machine; it won’t provide high returns just because you need them.”

When you do need higher investment returns because of a perceived shortfall in assets for a specific goal you generally have 3 options to remedy the situation:

(1) Adjust your expectations, and therefore, your lifestyle or goals.

(2) Increase your savings rate.

(3) Take more risk.

The first two options are for the realists while the third option is for the optimists.

It appears CalPERS is an optimist.

The Wall Street Journal reported this week that the behemoth public pension plan for the state of California would like to double down on risk by placing an additional $20 billion in private investments:

….

And here is the chief investment officer:“So the very first question is why private — why — why do we need private equity? And the answer is very simple. So if I could give you a one-line exact summary of this entire presentation would be we need private equity, we need more of it, and we need it now. So let’s talk about the first question, why do we need private equity? And the answer is very simple, to increase our chance of achieving the seven percent rate of return, and to stabilize employer contribution, and to help us to secure the health and retirement benefit of our members.

“…if you are trying to achieve seven percent return, and there’s only one asset class that is forecasted to deliver more than seven percent of the return, you need that asset class in the portfolio and you need more of it.”

He actually repeated the phrase “we need it now” four times over the course of this one meeting in reference to PE. There’s just a hint of desperation hidden inside the optimism.

It’s possible private investments have a higher expected return but there are a host of risks involved in this strategy.

The problem for Calpers is this: it has a sub-70% funded ratio, and it doesn’t look like the ratio will be going up any time soon. It sees an increasing contribution rate… that it knows its members will not be able to keep escalating.

They need returns.

Bad.

If you go to Ben Carlson’s original piece, the point is that private equity is a lot riskier than other asset classes.

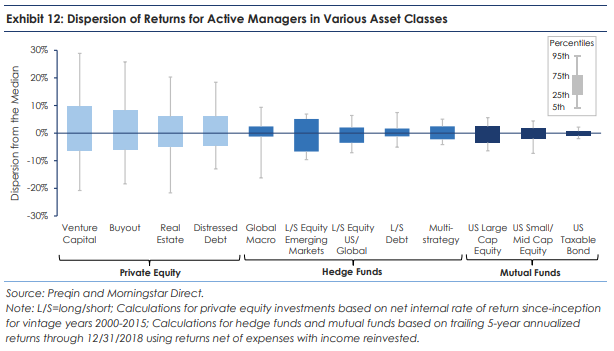

Those bars you see are variation in results. And the problem is the timing — Calpers has cash flows in and out. Private equity, by its very nature, is illiquid, meaning you can’t easily cash out.

Will those assets be able to provide needed cash flows when the time comes?

CALPERS IS NOT ALONE

In the paper I wrote with Gordon Hamlin, I investigated increasing allocations to “alternative asset classes”, of which private equity is one flavor. What these alternative asset classes have in common is that they’re difficult to value and are illiquid.

Allocations to these alternatives have been growing among public pension funds.

What have been the results?

But you don’t have to take my word for it. You can check out this paper from Cliffwater. Look for ‘ An Examination of State Pension Performance 2000-2018’ for download.

Here is a key exhibit:

Look at that blob of red dots. That’s the private equity. They’ve got relatively high return (vertical axis), and semi-high volatility (horizontal axis) … doesn’t look too bad, right?

That’s only 5 years.

Take a look at 18 years.

See that blob of red dots all the way to the right?

That’s private equity. Highest in riskiness… and the returns?

Well?

What do you think?

Well, ponder that one for the weekend.

Related Posts

Kentucky Pension Liabilities: Trends in ERS, County, and Teachers Plans

Nevada Pensions: Asset Trends

Public Pensions Interest Group Says: Your Money Creates More Value With Us!