The Meaning of the Word "Fault": Chicago Pensions Edition

by meep

I’m going to go on a little philosophical discourse for a moment, jumping off from a comment from one of the real people behind The Big Short:

When I spoke to some of the other real-life characters from The Big Short, I was surprised to hear that they thought that financial reform was pretty effective and that the system was much safer. Michael Lewis disagreed. In your opinion, did the crash result in any positive changes?

Unfortunately, not many that I can see. The biggest hope I had was that we would enter a new era of personal responsibility. Instead, we doubled down on blaming others, and this is long-term tragic.

…..

How do you think all of this affected people’s perception of the System, in general?The postcrisis perception, at least in the media, appears to be one of Americans being held down by Wall Street, by big companies in the private sector, and by the wealthy. Capitalism is on trial.

I see it a little differently.

If a lender offers me free money, I do not have to take it. And if I take it, I better understand all the terms, because there is no such thing as free money. That is just basic personal responsibility and common sense.

The enablers for this crisis were varied, and it starts not with the bank but with decisions by individuals to borrow to finance a better life, and that is one very loaded decision. This crisis was such a bona fide 100-year flood that the entire world is still trying to dig out of the mud seven years later.

Yet so few took responsibility for having any part in it, and the reason is simple: All these people found others to blame, and to that extent, an unhelpful narrative was created. Whether it’s the one percent or hedge funds or Wall Street, I do not think society is well served by failing to encourage every last American to look within. This crisis truly took a village, and most of the villagers themselves are not without some personal responsibility for the circumstances in which they found themselves. We should be teaching our kids to be better citizens through personal responsibility, not by the example of blame.

I want you to think about a theoretical situation.

Let’s say you are living a lavish lifestyle, racking up debt, paying just the interest (and maybe a little bit of principal, but only because that’s forced as part of minimum payments), and you are able to coast for a while.

Every week you buy $10 in lottery tickets, because your “plan” is to win the lottery, pay off your debts, and then live even larger.

But each week, you don’t win the lottery or you just get one of the booby prizes (like 5 “free” lottery tickets).

Eventually, you go bankrupt, unable to pay your minimum payments on debt, maxing out all your credit cards, and just plain out of cash.

So you sue the guy who sold you the lottery tickets.

It’s his fault, you see. You had a plan and the reason the plan didn’t work was because the guy who sold you the lottery tickets must have cheated you somehow.

Right?

WHAT DOES “FAULT” MEAN?

Now, it’s not a perfect analogy for what I’m getting at.

But when one’s financial “plan” had a very low probability of occuring, or if you don’t take into account very likely outcomes, it’s your fault for making the decision. It’s not the responsibility of the lottery ticket seller to remind you each time that your expected return is negative. You should have known that already.

Even if the lottery ticket seller says “hey, ya never know” and promotes the very improbable and very attractive upside, it’s still your fault if you shoved a bunch of money into the lottery.

Obviously, I’m trying to liken this to public finance and especially public pensions. The various governmental actors decided to give higher benefits, decided to invest in risky assets, decided to speculate with interest rate derivatives. And, most importantly, they decided to underfund the pensions even with all their lovely “plans”.

Unless there was outright fraud, then it is the fault of the pension plan sponsors and trustees that the pensions are in a poor condition. (Let’s not count out fraud, of course. But it doesn’t require fraud to explain the poor pension performance.)

REAL LIFE FINANCIAL LESSONS: IT’S NEVER DIFFERENT

I could make my analogy a little less stark by matching it to very non-hypothetical cases that I know about personally. For example, I knew several of my college buddies who racked up credit card debt, and wouldn’t exercise their employee stock options because of the tax hit and also the foregone upside. The market can only go up! up! up!

We graduated in the mid-1990s. A lot of people I know did this. I yelled at them ahead of time, trying to get them to cash out, diversify, etc.

I forebore from saying “I told you so” in 2001. I assumed they remembered.

Then there were other people I knew who day-traded on margin in the mid 2000s. And the people I know who have played with short positions.

All of these are risky propositions. Many of these people are doing well now, lesson having been learned. It was rough for many of them at the time — some of them got laid off when their respective companies were part of the dot-com bust, their stock options were underwater, and their employee stock holdings were worth much less than they had paid for them.

Yes, some of them bitched about the specific companies, but they didn’t sue, didn’t march in the streets — there was nothing nefarious about these specific company and sector failures. The boom-and-bust cycle has been around for a very long time (at least 300 years), and one is a fool if one says “This time it’s different!”

It’s never different.

This is why I have kept watch threads at the Actuarial Outpost (and why I write such long blog posts). If it’s just one thing, people will look at it in isolation and think it’s just one specific thing. Not some extremely long-term trend.

INTEREST RATE DERIVATIVES DISASTERS

One of my favorite texts with respect to this is John Hull’s book Options, Futures and Other Derivatives. When I was in grad school, I had the first edition. It’s now up to its 9th edition. The first edition did not have this chapter, but it came in fairly early on: derivatives disasters.

One of the most notable ones was Orange County, which had used interest rate derivative securities for… well, let’s take a look from a contemporaneous source:

FORTUNE — As was inevitable given the temper of the times, the December revelations about investment disasters in Orange County, California, were immediately converted into headlines with “derivatives” writ large. But in actuality, these newfangled concoctions were only a part of the problem that did the county in. The true roots of this fiasco were those ageless rascals, stubbornness and borrowed money.

The locus of all this trouble was the Orange County Investment Pool, into which the county and its cities, school districts, and special districts deposited their tax receipts. This fund owned almost no derivative contracts but had buckets of derivative securities. Most of these were “structured notes,” a name arising from the fact that the issuers of these notes, among them such parties as the Federal Home Loan Banks (FHLB), structure their terms to fit the investment wishes and opinions of particular institutional buyers. If he chooses, a buyer with strong convictions about the market may sign up for a package that combines the lure of above-market returns with extra risk. In other words, he rakes in money if he’s right about the market but loses his shirt if he’s wrong.

…..

Throughout the early 1990s, the manager of the Orange County pool, county treasurer Robert L. Citron, had a view — totally accurate — that interest rates were going down and that bonds were therefore going up. Taking this conviction to the structured-note market, where he often enlisted the help of Merrill Lynch, Citron performed like an Olympian. The yields earned by the Orange County pool from 1991 to 1993 were a marvel, running above 8.5% during a period when bond mutual funds were averaging about 7%. Mightily impressed, Orange County’s municipalities shoved money into the fund, raising the size of their deposits from around $3 billion in 1991 to $7.6 billion in 1994.

…..

The danger gathered force on February 4, 1994, when the Fed first tightened interest rates and sent fixed-income securities, including all those that Citron owned, into a grizzly bear market. By early December, the Fed had turned the screws five more times, and six-month Libor had gone from 3.6% to 6.8%. Wall Street’s brokers, who had provided Citron with most of his loans, were demanding additional collateral that he couldn’t supply. So some brokers sold their collateral, others mobilized to do so, and Citron’s whole jerrybuilt contraption tumbled.Weeks later, after a team of financial medics had overseen the liquidation of the fund’s portfolio, the toll could be calculated: Of the $7.6 billion that Orange County’s municipalities had put up, a stunning $1.7 billion had been lost. The ramifications for these investors are large: They are now struggling with their budgets, cutting back services, and fighting among themselves as to how the losses should be divided. And Orange County, of course, has filed for bankruptcy.

Meanwhile, Orange County and Merrill Lynch are no longer friends. The county has sued Merrill, charging that it “encouraged” Citron to invest in securities that, by the laws of California, were beyond the bounds of permissible risk. Merrill says it did nothing improper and denies being able to tell Citron anything.

Note the highlighting about borrowed money. What makes these situations really toxic is when leverage is boosted… to boost those sure-thing returns, doncha know.

Remember an unfunded pension liability is a kind of borrowed money. The pension funds are what are being borrowed from… at the valuation interest rate.

The Orange County bankruptcy was the largest municipal bankruptcy at the time. It’s been surpassed by two others since (Detroit and Jefferson County).

I bet it will be surpassed by even more.

BACK TO CHICAGO: DEMONIZING THE BANKS

So the Chicago teachers union has decided to try to Alinsky the banks on the other side of some interest rate swaps that are part of Chicago’s current leverage. Sorry, but I don’t think targeting the banks is going to help y’all right now. People can see what a bad actor Chicago had been even without the interest rate swaps. It’s just one of the very many shenanigans going on, and pretending they didn’t know the potential risk in interest rate swaps is idiotic given the Orange County experience.

If they were ignorant of the Orange County experience, then I say they were too ignorant to hold their positions.

So which is it, guys:

- the deciders were ignorant and duped with the interest rate swaps, thus unqualified to hold their positions, and therefore at fault for taking a position they shouldn’t have; or

- they did understand the derivatives transactions, and therefore are themselves at fault for making that decision

Either one is possible to me.

I can believe there’s a mix of such people on the board of trustees. I am willing to bet there are people who are too incompetent to be there. And then there were others who aren’t incompetent, but figured it would all work out well.

Guess what? It didn’t save your bacon from the undercontributions.

In any case, as the teachers union protests the banks, they find it’s tough to be pure:

The CTU has condemned Emanuel, the city of Chicago and CPS for “risky deals” with so-called predatory lenders, among them the world’s largest financial institutions.

An I-Team examination of the most recent teachers’ pension fund financials show that more than $505 million is invested in at least six of the very same financial institutions.

Among the firms where teachers’ money is currently invested, according to the most recent filing: JP Morgan, UBS, Citigroup, Deutsche Bank and Wells Fargo.

….

In a statement, a CTU spokesman said while CTU “does not control CTPF investments, we are proud that the CTU members that serve as trustees have helped move the fund toward responsible and progressive investment strategies.”The Chicago Teachers’ Pension Fund currently invests more than $10-billion dollars on behalf of 58,000 members. The fund’s executive director said that some of their investments in question are long-term that they buy and hold. Late last year, the pension fund filed a federal anti-trust lawsuit against some of its biggest investment banks, claiming a stranglehold on the market by so-called interest rate swaps.

Now, it is possible there are shenanigans going on with the banks. I assume it will come out in the case.

But it might turn out that Chicago took a bad bet — a bet they didn’t have to make.

They decided to make it.

OLDER DECISIONS FEED TODAY’S PROBLEMS

There is something to look at from over 20 years ago, when Daley got his mitts on the Chicago Public Schools. While there is a rending of garments over the state possibly taking control back, there is an argument to make that the trouble started from the moment Daley got control.

Take a look at this Newsletter from 1995.

There are multiple articles in there that relate to the pensions problem.

First, on the front page:

Sorry I can’t easily copy/paste the text. The olden days, ya know.

But the highlighted phrase:

…freedom to tap teacher pension funds and to fire unionizde blue-collar workers.

I have a feeling the first freedom was exercised a lot more than the second freedom.

But wait! There’s more!

Inside the issue, on page 7:

The whole section is worth reading, but it turns out they siphoned off pension funds to pay teachers higher salaries.

You know, higher salaries that translated into higher pensions, because the pension formulas are based on salary history.

Also note the appearance of the notorious 80% in the paragraph above. I could have forgiven a siphoning off the stuff that was above 100% (not much forgiveness, but at least they were maintaining solvency), but targeting 80%… when times were good?!

Finally, on page 9:

Nothing to emphasize, other than the “more harmonious” bit.

Which of course translates as “Mo Money”.

This stuff went down right before the big internet boom. No big deal, right? They got these boosts in the good times and then…

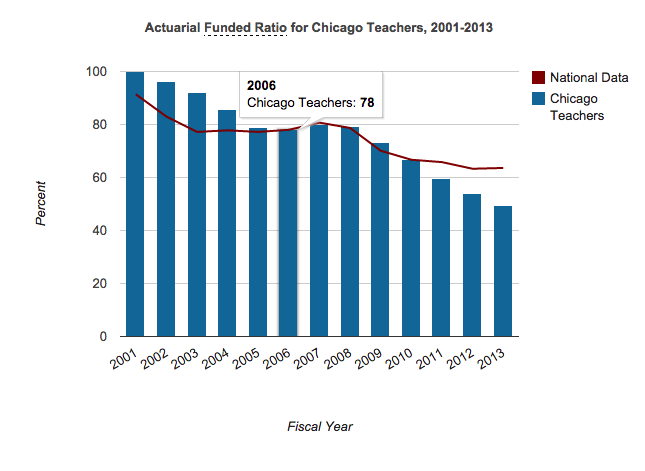

….oh right, all those higher salaries are baked in, not merely as increased salary costs right then, but as their future pension amounts. And when the market tanked:

Yeah, I don’t want to hear how it’s the banks’ fault.

You guys decided. Daley decided. The teachers asked for, and got, higher pay in the mid-1990s (with the expectation of high pensions decades later) with money taken from the budget that should have gone into funding the pensions.

And now your pension fund is in an execrable state.

Decisions have consequences. Quit blaming the banks.

Related Posts

State Bankruptcy and Bailout Reactions: Chicago Pleads, Bailouts Rationalized, and Bailouts Rejected

Taxing Tuesday: IRS Sends a Shot Across the Bow

Taxing Tuesday: I'm Sure Suing the Feds will Really Work for New Jersey