Mortality Monday: DEATH TO GEESE

by meep

Okay, one particular goose:

Several hundred dollars later, my windshield was made whole (and I’m still in NC), but I wondered: how many people die because they collide with animals?

ANIMAL ENCOUNTER DIAGNOSES

Going back to the mortality database from the U.S. in 2014, I needed to figure out what the relevant ICD-10 codes were.

ICD-10 codes are diagnoses codes, not only for death.

International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM)

The National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), the Federal agency responsible for use of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th revision (ICD-10) in the United States, has developed a clinical modification of the classification for morbidity purposes. The ICD-10 is used to code and classify mortality data from death certificates, having replaced ICD-9 for this purpose as of January 1, 1999. ICD-10-CM is the replacement for ICD-9-CM, volumes 1 and 2, effective October 1, 2015.

The ICD-10 is copyrighted by the World Health Organization (WHO), which owns and publishes the classification. WHO has authorized the development of an adaptation of ICD-10 for use in the United States for U.S. government purposes. As agreed, all modifications to the ICD-10 must conform to WHO conventions for the ICD. ICD-10-CM was developed following a thorough evaluation by a Technical Advisory Panel and extensive additional consultation with physician groups, clinical coders, and others to assure clinical accuracy and utility.

…..

The clinical modification represents a significant improvement over ICD-9-CM and ICD-10. Specific improvements include: the addition of information relevant to ambulatory and managed care encounters; expanded injury codes; the creation of combination diagnosis/symptom codes to reduce the number of codes needed to fully describe a condition; the addition of sixth and seventh characters; incorporation of common 4th and 5th digit subclassifications; laterality; and greater specificity in code assignment. The new structure will allow further expansion than was possible with ICD-9-CM.

One can go to the WHO website to browse animal-related stuff (and I’ll come back to them), but hey — let’s go to the wacky ICD-10 code posts!

AIN’T MEDICAL CODES WACKY?

There was a universal (in the U.S.) switchover to the ICD-10 codes in October 2015 (death records have been handled separately), and a lot of expert groups/transition groups/admin servicer groups posted stuff about the new wacky codes! (Just some of them. Nobody thinks getting into the details of cancer is all that wacky)

Lions & Tigers & Bears, Oh My! ICD-10 Codes Animal Style!

Here’s an interesting thought: when most people think of lions, they’re probably picturing Simba (or the man-eating Tsavo lions of 19th century fame). According to the new ICD-10 codes, however, the only lion you might encounter is of the marine variety. Should you happen to be struck by a sea lion (W56.12XA) or bitten by one (W56.11XA), rest assured that your medical billing codes will work out alright…and don’t go climbing over the fence at Sea World again!

Moving from the marine environment to a desert one, the Gila monster is one of the few venomous lizards native to the United States, and they’ve got a toxic bite. Instead of injecting venom like snakes do, “Gilas latch onto victims and chew to allow neurotoxins to move through grooves in their teeth and into the open wound.” This sounds pretty painful, but thankfully there’s a code for that: T63.111A (toxic effect of venom of Gila monster, accidental)!

A more benign and slightly less toxic injury is getting pecked by a chicken (W61.33XA). People at risk for this injury are city-slickers visiting farms and children chasing neighborhood birds. Simply collecting eggs for your breakfast might expose you to the terrible wrath of the mighty chicken guarding its progeny…though it’s not likely. Sadly, ICD-10 coding has not caught up with the dictionary when it comes to unfortunate henpecked souls.

Moving back into the realm of the serious, this is a rather gruesome chain of medical diagnosis coding: external causes of morbidity → exposure to animate mechanical forces → contact with non-venomous marine animal → contact with orca. When enough people have died from contact with a killer whale to make an ICD-10 code about it (W56.2), it may be time to assess human proximity to these wild animals.

A GIF guide to the most important animal ICD-10 codes; AKA an incomplete guide of animals to avoid [I am not going to include the GIFs]

1.W.56.52 Struck by other fish

This is a real-life concern for people in Illinois, y’all—carp just fly up out of the river and smack people in the face. Also, with regards to those guys who go around sticking their hands into catfish holes to try to grab them: Stop doing that. Catfish have stingers and they’re barely good to eat. Best to stay away from the whole undisclosed-variety-of-fish that necessitates this code.

2. W56.22 Struck by orca

We assume that anyone inputting this code will be quietly humming “Will You Be There” while they’re doing it, and that would be a mistake, folks. Orcas will not be there for you, they are seal-killin’ machines that only look cute and cuddly. Don’t be this kid. It won’t end well.

3. W61.1 Contact with macaw

At Healthcare Dive, we typically do whatever we can to avoid coming into contact with semi-domestic birds that bite, but unfortunately, others do not share our good sense. Addendum: Also worth avoiding Australia entirely, where hordes of wild cockatoos rove the countryside like marauding sky-dogs.

4. W55.21 Bitten by a cow

Look. Don’t be fooled by their placid bovine expressions. Cattle are not to be messed with. If the cloven-hoof thing wasn’t enough to convince you, there’s an entire Wikihow dedicated to combating bovinophobia. Stay away, people. Stay away.

…..

8. V80.2 Occupant of animal-drawn vehicle injured in collision with pedestrian or animalOkay, my coders and heroes, this isn’t so much an “animal” to avoid as a “situation.” Obviously, since this is 2015, we shouldn’t have to have this ridiculous conversation about not allowing a living animal to drag you around in a death trap on wheels. N/A.

10. W56.41 Bitten by shark

Fine.

I don’t actually get that level of detail in the death records. For example, I get just the bit before the decimal, so I get W55 as “Bitten or struck by other mammals”

But there were plenty of things in the Exposure To Animate Mechanical Forces — Codes W50-W64 block (Not all are animals – some are people biting people); a variety appear in vehicular accidents (such as V40: Car occupant injured in collision with pedestrian or animal; and X20-X29: Contact With Venomous Animals And Plants.

DEATH AWAITS YOU ALL WITH NASTY BIG POINTY TEETH

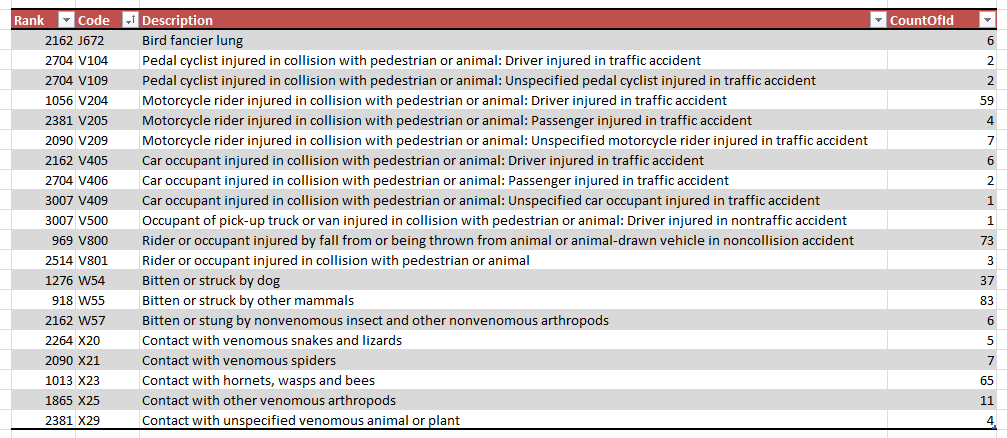

Here’s my table:

Not very many people died this way — I started looking at zoonotic diseases, but changed my mind about looking at that. Those numbers are also small — only one death from rabies, for example — but I had more of a “collision” theme with animals. I kept in Bird fancier’s lung because I felt like it.

Let’s sort this by number of deaths:

That’s a total of 384 deaths, and it looks like the primary cause is being attacked by some non-dog mammal. I would assume the second cause is primarily people being thrown from or falling off horses. Alas, most of the vehicular accident codes do not distinguish between hitting a person and hitting an animal.

Some people do get killed via animal through the windshield:

(It looks like that person survived… obviously, the deer didn’t.)

If the goose I ran into yesterday had managed to punch through the windshield like that deer and smack my head off (Hmm, about 9600 Newtons… okay, I’m not calculating this. Right now.) — anyway, that would have been coded as a V405: Car occupant injured in collision with pedestrian or animal: Driver injured in traffic accident

.

We can see from the table that 6 people died that way in 2014.

One reason so few have died that way is automotive safety glass. Yay, safety glass!

Dumb goose.

Seriously, I hear about cars colliding with deer all the time, and problems planes have with geese, but this is the first time I heard of a low-flying goose getting smacked by a car.

But then, I had never gone looking for such stories. Here’s one. As you can see from my pic above, while the goose left some feathers, it didn’t get through the window, possible because it didn’t do a head-on collision, but was merely trying to cross the highway.

HOW MANY BIRDS ARE KILLED BY CARS?

Supposedly, loads of birds die this way…:

Bird deaths from car crashes number in millions

….

Hunters bagged a mere 19 million U.S. ducks and geese in 2012, according to federal statistics, and a quarter-million to a half-million birds a year die after hitting wind turbines. Among well-studied causes of death tied to humans, only cats and collisions with buildings lead to more bird deaths than traffic does, the study says.“We don’t really pay attention to or talk much about this issue of vehicle collisions. … We’re all used to driving,” says Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s Amanda Rodewald, who’s not affiliated with the study. But the new estimates show the toll of vehicles is “pretty staggering,” she says. “I had no idea.”

To compile a nationwide estimate of avian road kill, the study’s authors extrapolated from 13 small-scale surveys of birds that died after being hit by vehicles. The results show that 89 million to 340 million birds suffer fatal injuries from vehicle encounters annually, a range that accounts for dead birds taken by scavengers, carcasses missed by researchers and other uncertainties, the researchers report in an upcoming issue of The Journal of Wildlife Management. Previous research had pegged bird deaths from vehicles at 60 million to 80 million.

That sounds awfully high to me. But then:

Birds hit by cars are, well, bird-brained:

What’s the difference between birds that get killed by cars, and those that don’t?

The dead ones tend to have smaller brains, scientists who performed 3,521 avian autopsies said Wednesday.

What might be called the “bird brain rule” applies to different species, depending on the ratio of grey matter to body mass, they reported in the journal Royal Society Open Science.

Crows, for example, have big brains relative to their size, and have shown a remarkable knack for navigating oncoming traffic.

While picking at road kill on Florida highways, earlier research showed, the scavengers learned to ignore cars and trucks whizzing by them within inches, but would fly away just in time when threatened by a vehicle in their lane.

….

Undamaged brains from birds killed in accidents—weighed to within a hundredth of a gramme—were consistently smaller, he said.Grim tally

At the same time, other organs—liver, heart and lungs—all had the same mass.

In total, the researchers examined 251 different species.

The finding raises the question of whether certain species, and certain populations within species, have evolved over the space of dozens of generations such that birds with car-dodging abilities have become more common.

Most of the birds I’ve noticed in possible danger from cars have been those hanging out on the road — that is, not flying.

The State of the Birds annual report estimated in 2014 that 200 million birds perish on the road every year in the United States alone.

Estimates for Europe are lower, but worldwide the grim tally is certainly in the hundreds of millions.

But there are an estimated 300 billion birds in the world, so the death toll is still only a fraction of one percent.

….

The same report estimates that 2.4 billion birds fall victim in cats every hear in the United States.

Okay, I’m not going to worry about big bird collisions for now, but dammit, there had better be no geese lying in wait on the highway tomorrow, out for revenge for their fallen comrade.

FINAL ADDENDUM: Fabio killed a goose with his face (and a roller coaster)…I dunno, it’s at Clickhole…

Related Posts

Mortality with Meep: Comparing COVID-19 with Historical Mortality and Prior Pandemics

Childhood Mortality Trends, 1999-2021 (provisional), Ages 1-17 -- Good News for Young Kids, Not for Teens

Mortality Monday (with a little Trumpery): Supreme Court Probabilities Take 2