Are Public Pensions in a Crisis? Part 4: On Closing DB Plans and Replacing with DC Plans

by meep

Okay, so we’ve had two papers so far — one claiming that it can be okay for public pensions to be perpetually underfunded or even go to pay-as-they-go, the other implicitly saying the same thing, but also asking for accounting changs (some which would help indicate which pension sponsors are more precarious, but still with stuff I’m not liking.)

So let’s look at one strategy that some pension sponsors have done to try to stop the bleeding: close their DB plan and switch new employees over to a DC plan.

There was a paper put out on why that was a bad idea, based on actual experience with some places that did this. Note: this is not actually something new, but an update of something that had been done before. And that I had written about before.

COVERAGE OF PAPER

Plansponsor: Case Studies Suggest Move From Public Pensions Hurts Taxpayers

Experiences of four states that moved from traditional defined benefit (DB) plans to cash balance or defined contribution (DC) plans show it did not address existing pension underfunding and increased costs for these states.

A new series of case studies finds that states that shifted new employees from defined benefit pensions to defined contribution or cash balance plans experienced increased costs for taxpayers, without major improvements in funding.

The research, published by the National Institute on Retirement Security (NIRS), also indicates that the move away from pensions cuts employees’ retirement security and that employers may face increasing challenges hiring and retaining staff to deliver public services.

The research looked at four states that closed their pension plans in favor of alternative plan designs: Alaska, Kentucky, Michigan and West Virginia.

According to the study report, “Enduring Challenges: Examining the Experiences of States that Closed Pension Plans,” in Alaska, closing the pension plans has not helped the state manage the existing unfunded liability. Despite a $3 billion infusion of the state’s financial resources, the combined unfunded liability for pension benefits was higher in 2017 than it was in 2005. Alaska has managed to improve the funded status of both its plans modestly after increasing its commitment to funding, yet the unfunded actuarial accrued liability for pension benefits has increased in the pension plans since 2005. And, many workers face a retirement with no Social Security or pension.

In Kentucky, the legislature enacted a new tier of benefits for plans in the Kentucky Retirement System (KRS). Public employees hired since January 1, 2014, participate in a cash balance hybrid plan instead of the pension plan. This move was positioned as a way to improve KRS funding. One of the KRS plans (KERS Non-Hazardous) was funded in fiscal year 2004 at 85.1%. By fiscal year 2018, the funded status was down to 12.88%.

Ugh. Kentucky.

Anyway, let’s take a look at the paper.

PAPER ON STATES THAT CLOSED DB PLANS

Enduring Challenges: Examining the Experiences of States that Closed Pension Plans

The new research, Enduring Challenges: Examining the Experiences of States that Closed Pension Plans, provides case studies in four states that closed their pension plans in favor of alternative plan designs: Alaska, Kentucky, Michigan, and West Virginia. The report’s key findings are as follows:

Switching from a defined benefit pension plan to a defined contribution or cash balance plan did not address existing pension underfunding as promised. Instead, costs for these states increased after closing the pension plan.

Responsible funding of pension plans is key to managing legacy costs associated with these plans. The experience of the four states shows that changing benefits for new hires does not solve an existing funding shortfall.

Change in plan design has resulted in greater retirement insecurity for employees. In West Virginia’s case, this led the state to reopen the closed pension plan.

Workforce challenges are emerging as a result of the retirement benefit changes. Alaska is experiencing increased difficulties recruiting and retaining public employees since the pension plans were closed to new hires. The Alaska Department of Public Safety lists the ability to offer a pension as a “critical need” for the department.

There are two things I highlighted. I happen to agree with the other items inasmuch that DC plans are riskier for employees and that most of these states mismanaged the funds before and after they were closed. Just closing the DB plans doesn’t make up for hideous funding situations.

Those are just the key takeaways above. Here is the full paper, and here are accompanying slides. I attended the webinar when they gave it earlier in the month (August 13), and it seemed quite reasonable to me, and some of the conclusions I entirely agree with.

OTHER PEOPLE’S REMARKS AND AN OLD REMARK FROM ME

The National Institute on Retirement Security (NIRS) was charged by their public employee union clients to come up with a report to try and scare states away from moving their employees from Defined Benefit to Defined Contribution plans. This is what they came up with and, after reviewing what presumably are the facts they want you to know, an honest interpretation arrives at exactly the opposite conclusion.

…..

What is conveniently missing from the NIRS analysis is that Defined Contribution plans have to be 100% funded. For example in Alaska the unfunded liability may have increased in dollar terms but the funded percentages went up for the Defined Benefit Plans to about 70% and, when the fully funded Defined Contribution plans are included, would total about 80% for the system.On account of the politician/actuary cabal that consistently understates Defined Benefit contributions these plans are going bankrupt. What is it about the Defined Contribution concept that the unions and NIRS despise? The transparency?

Elizabeth Bauer had some remarks: (read the whole thing)

Let’s start with a brief reminder: when one reads reports of pension underfunding in a given state, this is always based on benefits for existing employees for work performed up to this point in time, with relevant incorporation of the impact of projected pay increases for current employees and projected COLA increases for all.

This is a debt that will continue to exist regardless of whether new employees are moved into another type of plan. If a pension reform is implemented in which existing accruals are left untouched, this debt will continue to exist. Only in the case in which past accruals are affected will the existing debt be reduced — a reduction which might take the form of calculating retirement benefits using pay at the time of a benefit freeze rather than at retirement or reducing/freezing COLA adjustments, to take two examples that might be a part of a typical public pension reform rather than a more drastic bankruptcy-driven version.

…..

In a switch to a Defined Contribution system for new employees, assuming a fair and appropriate employer contribution, in the short term, overall system expenses will increase as the new employees receive percent-of-pay contributions that are higher than the very small accruals the employer would have to reserve for them in a DB plan. And, what’s more, employees who are required to contribute to the plan may even subsidize the plan itself, relative to their accruals, in their younger years. (The negative normal cost of Illinois’ Tier 2 employees is an extreme case due to the benefit cuts, but this is true of contributory plans generally-speaking.)But the benefit in moving to a Defined Contribution system, or any similar system (e.g., a risk-sharing system, a level-accrual cash-balance system), is to ensure that the state pays what it promises rather than pushing off contributions into the future for a later generation, and to prevent the state from overpromising and sticking future generations with the bill.

…..

The bottom line is this:It is entirely possible for a state or city to properly fund a Defined Benefit pension plan; it just takes discipline, plus either a risk-sharing design or a willingness to suck it up and pay more when the math requires it.

It is likewise possible under either a Defined Benefit or Defined Contribution system for the state to promise a retirement benefit that meets its employees needs for adequacy while not overspending. (Employers are also perfectly free, in a Defined Contribution system, to make contributions to employees unconditionally rather than, as is typical in the private sector, requiring a match.)

But it is only a Defined Contribution program that can wholly remove from legislators the temptation to ask (OK, require) future generations to pay for this year’s benefit accruals, sometimes leaving them with bills of such magnitude as to imperil provision of basic human services. Only a Defined Contribution ensures that the retirement benefit is always by definition 100% funded. And only in a Defined Contribution program is the benefit defined up front and transparent to all.

And here is my remark from an older post:

“1. Closing a defined benefit plan does not reduce costs and usually will increase costs, at least in the near-term”

….

1. This is just stupid. If one has a fully-funded DB plan for retirees and you just stop accruing further DB benefits for participants and their part is already fully-funded, then nothing is more expensive. You go from an uncertain cost to a certain cost.But what they mean here is that if the plans are underfunded, and you have no new entrants, you can’t do certain tricks that help low-ball contribution amounts. Because, as Warren Buffet said, when the tide goes out, you find out who has been swimming naked.

The pension promises cost what they cost, ultimately. Changing not-yet-accrued benefits to a different system doesn’t make the already-accrued benefits more expensive.

Now, what happens is that when you close a DB pension, the allowable practices one can use to lowball the liability cost get more constrained.

You can’t pretend there’s a growing payroll in the future that one can amortize the unfunded liability over. You can’t keep rolling that amortization period. And, generally, pretending one can achieve a “steady” 8% return in the shorter time remaining… yeah. You get a market hit, you can’t pretend you’re going to make it up over the remaining lifetime of the closed block.

Much of the increased cost comes from a shorter period they have to make the pensions whole. It’s like going from a 30-year mortgage to a 15-year mortgage — the monthly payments for the 15-year mortgage will be higher, even if it’s at a lower interest rate (as it usually is) than the 30-year mortgage.

A short term strain for a certain benefit and uncertain cost to provide it going to a long-term system of steady cost… well, ultimately, they may be winners.

Again, to be very fair, I really value guaranteed retirement benefits, but the problem is when it’s 100% guaranteed. These promises are very expensive. They’ve just been using tricks to make the promises look less valuable than they actually are. When you close a DB plan, the real, higher costs become evident quickly.

But, we’ll also see that the specific plans were extremely poorly funded before they were closed, and post-closure behavior may have improved a little, but none of them are fully-funded.

ALASKA’S SPECIAL SITUATION

Here is the pertinent slide on Alaska from the accompanying presentation:

This is the problem for Alaska: it is not a congenial location for most people. This goes for places like Maine, North Dakota, etc. People want to live in Southern California for the climate (though the real estate prices may not be so congenial). Also, with a rural situation, there is the consideration of opportunities for spouses and children.

Given that people generally don’t want to live at such a high latitude, and many like having a bit higher population density than Alaska, you need to make any positions you need filling in such locations to be attractive. Obviously, a DB pension can be such a thing.

That’s not a matter of funding. That’s a matter of having a pay and benefits package that can attract the people you need. I have no dispute that a DB pension (that one has a good chance of actually receiving) is very attractive.

I don’t know about Alaska’s old DB pension, but many teachers’ pensions require five to ten years of working in the system before being eligible for the pension. If you leave before you’re vested… you get nothing. Oh look, some “reforms” involved increasing vesting periods:

Illinois was one of the states that increased its vesting requirements. Before 2011, teachers were required to work at least five years to be eligible for a minimum pension. In 2011 Illinois increased the vesting period as part of a pension reform law to reduce the state’s unfunded pension liability. The law (Public Act 96-0889) created two tiers of teachers. Teachers in Tier 1, those who were employed before January 1, 2011, continue to vest after five years of services. Tier 2 teachers are those who entered employment on or after January 1, 2011. They must serve 10 years before reaching eligibility for a pension.

I knew Tier 2 benefits were worse than Tier 1 (and that the Tier 2 teachers are subsidizing the Tier 1… and I’m not sure how this can be legal), but I didn’t realize they were that bad.

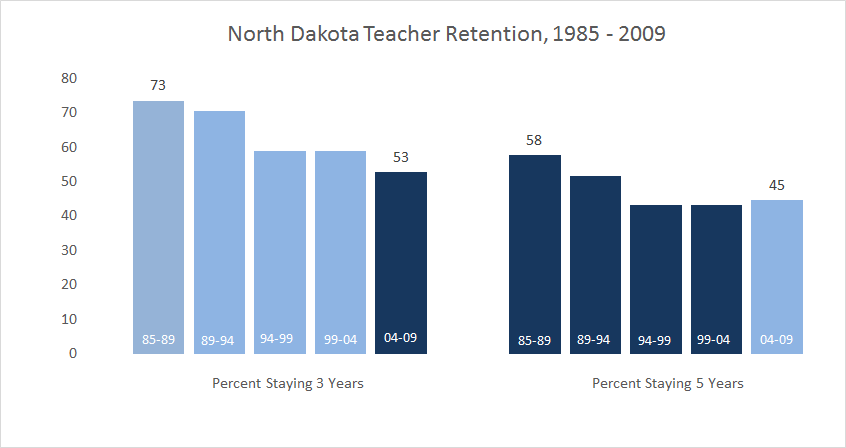

That said, one wonders the cause-and-effect being noted in the first place. This piece notes that North Dakota has had high teacher turnover, even without changing their DB pensions.

My understanding has been that a lot of school systems have had bad turnover for early career teachers. This may not be unique to North Dakota. Even for the places that have not reduced pension benefits.

All that said, I can totally believe that a location that is “geographically challenged” may want to have nicer benefits than other places, in order to attract employees. That is reasonable. But most states aren’t Alaska.

ON THE FUNDED RATIOS FOR THE PENSIONS IN QUESTION

John Bury mentioned above that one should probably combine the funded ratios for the DB and DC plans to have a fair idea of the financial position for the state. But I won’t do that (mainly because that’s not easy for me to get the data to actually calculate that.)

I’m going to use the graphs via the Public Pension Database for each plan. Here they are:

Alaska Teachers: (closed 2005)

Alaska PERS: (closed 2005)

Kentucky ERS: (non-hazardous switch to hybrid in 2014)

Michigan SERS: (closed 1997)

West Virginia Teachers: (closed in 1991, reopened in 2005)

Now, each of these have their own trajectory — different date of closure, and one reopened in 2005.

These do not look good…. but seriously, I could cherry-pick pensions that neither closed, nor changed, who have equally bad patterns (except Kentucky ERS. YEESH. Kentucky is a special case of a bad actor on pensions, in all ways.)

I agree that simply closing the DB plan to new entrants did not necessarily lead to better funded ratios. But leaving the DB plans open would not have led to better results, either. They talk about escalating costs — well, there are several open plans that have escalating costs, and it usually comes from reality catching up with the accounting and valuation tricks.

SECURITY DOES NOT COME FROM MAKING A PROMISE, IT COMES FROM FUNDING THE PROMISE

The paper itself is primarily the case studies, and the fact patterns are such that I could probably pair them up with similar plans that did not close their DB plans. Alas, I’m not being paid to do this – I mainly comment on other people’s work.

But let me go back to one of the key takeaways from the top of the post:

Responsible funding of pension plans is key to managing legacy costs associated with these plans. The experience of the four states shows that changing benefits for new hires does not solve an existing funding shortfall.

Of course, keeping benefits the same for new hires also does not solve an existing funding shortfall. It can even make the situation worse if the pension plan benefit and funding design tends to lead to worse situations. But they didn’t address that, did they?

Here is my point (also taken from Elizabeth Bauer): public pensions are in crisis in places were they are in crisis because of benefits already accrued. This is what makes it so difficult. If it were just a case of future benefits, then solutions would be easier. But the problem is that the unfunded liabilities — that’s of benefits already earned — that are getting to a level where they simply cannot be paid with a reasonable expectation via raising taxes (where all the contributions come from).

People keep acting like that simply that the promise was made to public employees means that they have retirement security, and that they are in a more precarious position if it were a pure DC plan.

But the DB plans do have market risk embedded in them… and if the government has not reasonably set up benefits nor funded them appropriately (and invested for them appropriately), then public employees and retirees are still open to retirement insecurity.

It is better to come up with more stable approaches, as seen with Wisconsin and New Brunswick, to provide a certain basic guaranteed benefit plus some variable aspects on top — the contributions required for such plans are far more stable than the escalating costs we often see with plans that have been making “full payments” all along.

Closing DB financially-stressed plans is akin to “stop the bleeding” in trauma situations: no, stopping the bleeding does not fix the problem, but it stabilizes the situation so that people can actually be saved.

I would rather they not fully-remove guaranteed income elements – I think at least a little bit of the pension should be guaranteed income, just not 100% of the benefit. But I cannot blame the states that have taken these measures.

Just don’t pretend that plans in deteriorating situations are really made much better by letting them continue to bleed out.

PUBLIC PENSIONS IN CRISIS SERIES

- Part 1: My opinion

- Part 2: Is pay-as-you-go sustainable?

- Part 3: Is it just an accounting problem?

- Part 4: On closing DB plans and replacing with DC plans

- Part 5: On Bonds and Bailouts

Related Posts

State Bankruptcy and Bailout Reactions: Chicago Pleads, Bailouts Rationalized, and Bailouts Rejected

Arguing against the Public Pensions "Truths" and "Myths"

Taxing Tuesday: Don't Worry, Gamers...plus: Soda Tax Retrospective!