MoneyPalooza Monstrosity: It Passed! More on the Multiemployer Pension Bailout

by meep

Well, they did it. They finally did it.

You maniacs!!

I will be looking at the multiemployer pension bailout more in this post, and the state/local government bailout in a later post.

The state of the bailout: FULL AND MORE…..

NYT: Rescue Package Includes $86 Billion Bailout for Failing Pensions

Tucked inside the $1.9 trillion stimulus bill that cleared the Senate on Saturday is an $86 billion aid package that has nothing to do with the pandemic.

Rather, the $86 billion is a taxpayer bailout for about 185 union pension plans that are so close to collapse that without the rescue, more than a million retired truck drivers, retail clerks, builders and others could be forced to forgo retirement income.

….

Both the House and Senate stimulus measures would give the weakest plans enough money to pay hundreds of thousands of retirees — a number that will grow in the future — their full pensions for the next 30 years. The provision does not require the plans to pay back the bailout, freeze accruals or to end the practices that led to their current distress, which means their troubles could recur. Nor does it explain what will happen when the taxpayer money runs out 30 years from now.

Oh, that should be fun.

For many of those getting the pension backpayments in the few plans that already had benefit cuts, they probably figure they’ll be dead in 30 years and won’t worry.

I do wonder about the MEPs that already completely failed, putting participants on the extremely low PBGC guaranteed payment amounts. Do they get their pension payments back? Or is it just the ones that managed to just barely hang on until they could get their full bailout?

On Friday, Senator Chuck Grassley, Republican of Iowa, introduced his own legislative proposal for the failing pension plans, which he said would bring structural reforms to make them solvent over the long term. He called the measure put forth by Democrats “a blank check” and tried to have it sent back to the Senate Finance Committee for retooling.

“Not only is their plan totally unrelated to the pandemic, but it also does nothing to address the root cause of the problem,” Mr. Grassley said in a statement. His motion failed in a vote of 49 to 50.

At 87 years old now, Chuck Grassley doesn’t have to worry about what will happen in 30 years, when the money is cut off. He has been trying to get various MEP reforms through Congress, but as one side wanted nothing less than a no-strings-attached bailout, he wasn’t very successful.

There are multiple root causes, especially for the one MEP that was threatening to pull the whole system down: Central States Teamsters plan. They would have pulled down the system by 2025/2026, and there would at least have been a bailout of the PBGC.

But the default case would have been the MEP participants getting the extremely low guaranteed amounts (which would have been enough to wipe out the PBGC multiemployer program). Not getting full payments.

Here, they get full payments, at least for 30 years…. or at least until the rules get changed again. But more on that below.

….Or is it really a full bailout?

Using taxpayer dollars to bail out pension plans is almost unheard-of. Previous proposals to rescue the dying multiemployer plans called for the Treasury to make them 30-year loans, not send them no-strings-attached cash. Other efforts have called for the plans to cut some people’s benefits to conserve their dwindling money — such as widow’s pensions, early retirement subsidies and pensions promised by companies that subsequently left their pools.

This was already a law passed by Congress. I suppose I should grab the info from this page: The Multiemployer Pension Reform Act of 2014, which is the one allowing for benefit cuts. The record could disappear.

It looks like the Pension Rights Center captured the info in an August 2020 post, and I will calculate a few things below.

Back to the NYT piece:

The federal government does provide a backstop for certain failing pension plans through the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation, which acts like an insurer and makes companies pay premiums, but does not get taxpayer dollars. Currently, the pension agency has separate insurance programs for single-employer and multiemployer pensions. The single-employer program is in good shape, but the multiemployer program is fragile. As of 2017, the country’s 1,400 or so multiemployer pension plans had a total shortfall of $673 billion.

$673 billion… versus the supposed cost of this bill: $86 billion. The supposed cost of the bill is about 13% of the total shortfall (of 2017… which may be bigger or smaller now).

Is this really a full bailout?

To be sure, some of those funding shortfalls are very small compared to the full obligation for the specific pension plan. But that was because the unions sponsoring said not-egregiously-underfunded pensions were expecting their members to be greatly harmed if their pension funds ran out of money.

But this new bill is showing them that hey, they were suckers for trying to fully-fund their plans.

A bailout needed before 2025

Back to the NYT:

One huge Teamster plan, in particular, is expected to go broke in 2025, and when the pension agency starts paying pensions to its nearly 200,000 retirees, its multiemployer insurance program will go broke, too, according to the agency itself. That would leave the roughly 80,000 other union retirees whose pensions the agency now pays without their payouts.

Interesting editorial choice not to actually name the plan. (Yes, it’s Central States Teamsters. Here is a piece from 2014 where they’re actually named, but I believe that’s an op-ed.)

The new legislation changes that. It calls for the Treasury to set up an $86 billion fund at the pension agency, using general revenues. The agency would be required to keep the money separate from the funds it uses for normal operations. It would use the new money to make grants to qualifying pension plans, allowing them to pay their retirees. The Congressional Budget Office estimated that 185 plans were likely to receive assistance, but as many as 336 might under certain circumstances.

And “unexpectedly” far more than 336 plans will ask for money! What’s to stop the 1,400 MEPs trying to put their pension obligation onto this program?

Of course, some of the plans are very small, so counting the number of plans applying isn’t terribly meaningful (but seriously, there will be a lot of plans deciding why be a sucker? Free money is free money!) — what I really want to know is what will happen when that $86 billion runs out.

Because I thought it was some sort of 30-year blank check, but no, it sounds like the check isn’t blank, but that specific amount.

Plans cut before the pandemic

The grants are intended to pay the retirees their full pensions, a much better deal than the pension agency’s regular multiemployer pension insurance, which is limited by statute to $12,870 per year. Many retirees in the soon-to-be rescued plans have earned pensions greater than that.

The taxpayer money will also be used to restore any pensions that were cut in a 2014 initiative that tried to revive troubled plans by trimming certain people’s pensions. The stimulus bills — there is a House version and a Senate version that have minor differences — call for the affected retirees to get whatever money was withheld over the past six years.

That is a complete clawback. As noted above, the bill that allowed for these benefit cuts was passed in 2014, the earliest applications for benefit cuts were in 2016, and the first benefit cuts approved was in 2017 (and there would be delay from approval to actually cutting).

So I took the record from the Pension Rights Center, and looked at only the plans with benefit cuts already fully approved. Next to them is the projected insolvency date (aka when all the cash runs out), and, if available, the number of plan participants.

- Alaska Ironworkers Pension Plan 2031 1,573

- Composition Roofers 42 Pension Plan 2030 [not available]

- IBEW Local Union 237 Pension Fund 2028 [not available]

- International Association of Machinists of Motor City Pension Fund 2026 1,197

- Iron Workers Local 17 Pension Fund 2025 2,067

- Ironworkers Local 16 Pension Fund 2032 1,066

- Local 805 IBT Pension & Retirement Plan 2023 2,065

- Mid-Jersey Trucking Industry and Local 701 Pension Fund 2054 1,887

- New York State Teamsters Conference Pension and Retirement Fund 2027 34,639

- Plasterers & Cement Masons Local 94 & Pension Fund 2026 111

- Plasterers Local #82 Pension Plan 2034 309

- Sheet Metal Workers Local Pension Fund (OH) [not available] 4,500

- Southwest Ohio Regional Council of Carpenters 2036 5,501

- Toledo Roofers Local No 134 Pension Plan 2031 473

- United Furniture Workers Pension Fund A 2021 9,896

- Western PA Teamsters & Employees Pension Plan 2029 22,000

- Western States Office & Professional Employees Pension Fund 2036 7,463

So, just adding up the number of participants of the plans with benefit cuts already approved, that’s about 95,000 very happy people today.

Y’all should party — you guys are going to be first in line for this bailout.

Why are the plans so underfunded?

Back to the NYT:

The legislation requires the troubled plans to keep their grant money in investment-grade bonds, and bars them from commingling it with their other resources. But beyond that, the bill would not change the funds’ investment strategies, which are widely seen as a cause of their trouble.

Um, sorry, no. I don’t think their investments caused the trouble. I believe their investment strategies are because of their trouble. I keep running into this cause-and-effect switcheroo in public pensions.

It’s not that the pensions are slavering to get into alternative asset classes, which then draws the funds into a burning ring of fire. It’s that they want the pensions to be relatively cheap compared to their real costs, so they go chasing waterfalls.

And then the ring of fire thing.

Here is my opinion:

- many of these plans funding (and valuation) assumption were built on the concept that more money would come in the future

- some of that is in their investment return assumptions and some of that is in their future contribution amount assumptions

Some of these ailing MEPs have seen the industries that their unions are in obliterated as the economy changes. It’s not merely that fewer companies in the U.S. want to use union labor and shift operations to places like South Carolina, which does not have much in the way of non-governmental unions. It’s also that all sorts of things are just not needed as much anymore, and other things are being produced.

As for the investment assumptions, I don’t fault their pension funds for not achieving a steady 7%/year. That’s just not realistic. Yes, many of these funds have gone into riskier asset classes to try to achieve these yields (which leads to higher volatility, and sometimes large losses), but that was because the contribution amounts have not been enough to attain solvency at more reasonable investment targets.

But let me not get ahead of the article:

For decades, multiemployer pensions were said to be safe because the participating companies all backstopped each other. If one company went under, the others had to cover the orphaned retirees. Because they were considered so safe, multiemployer pensions never got much oversight.

While companies that run their pension plans solo must follow strict federal funding rules, multiemployer plans do not have to. Instead, the companies and unions hammer out their own funding rules in collective bargaining. Both sides want to keep the contributions low — the employers to reduce labor costs, and the unions to free up more money for current wages. As a result, many of the plans have gone for years promising benefits without setting aside enough money to pay for them.

You keep contributions low by assuming you get more money later, whether through investment returns or growing contributions later. Neither of which necessarily came.

In hopes of making up for the low contributions, the plans often invest unduly aggressively for their workers’ advancing age. In bear markets they lose a lot of money, and they can’t ask the employers to chip in more because the employers are often struggling themselves.

In investment/finance terms, there is often a high correlation between the pension fund investment performance and the pension sponsor financial performance.

In less fancy terminology, many of these employer companies do poorly at the same time the market does poorly, so when the pension fund asset values go down, the employers are unable to contribute more to the pensions.

It does not make for a stable system.

The new legislation does nothing to change that dynamic.

“These plans are uniquely unable to raise their contributions,” said Mr. Naughton, whose clients included multiemployer plans when he was a practicing actuary. “When things go well, the participants get the benefits. If things go badly, they turn to the government to make it work.”

It’s interesting that Naughton is quoted.

An ex-actuary speaks

I didn’t quote Naughton earlier. Here he is in his mention:

“Imagine that you have a college-aged kid who runs up $1,500 in credit card debt,” said James P. Naughton, an actuary now teaching at the University of Virginia’s Darden School of Business. “If you give him $1,500 and you don’t do anything else, the odds that the problem is going to get fixed are pretty low.”

Party time!

Naughton has testified to Congress in the past over MEPs. From March 2019: “The Cost of Inaction: Why Congress Must Address the Multiemployer Pension Crisis”.

Here is a key portion of his testimony:

The first decision relates to past underfunding, and entails figuring who will cover the shortfall

that has arisen because of the difference between what the unions promised their members and

what the unions collected from employers to cover these promises. This is not an easy decision,

as many union members who relied on the promises made to them by their union leaders are

facing severe financial consequences if their pensions are eliminated. In addition, employers vary

in their ability to absorb the increased contributions that are currently required or may be

required in the future to fund these plans. *The PBGC recently reported that the system is $638

billion underfunded for 2015.*

Recall from the NYT piece, that the underfundedness was $673 billion in 2017.

Anyway, this first question has been answered with the bailout bill: the American taxpayer (and bondholder) is bailing out a small portion of the past underfundedness for MEPs as a whole system, which will be a large portion of specific MEPs.

Back to Naughton:

The second decision entails figuring out how to ensure that the current level of underfunding

does not deteriorate further and how to put the system on a sustainable path going forward. The

urgency of this step is evident in the events that have occurred since legislative action was first

taken to address the multiemployer pension crisis in 2005—since that time, the level of

underfunding has increased by approximately $400 billion on a PBGC basis.

This, too, has been partly answered.

In short, the new bailout bill has incentives towards ever-deteriorating funded ratios for the plans not already being explicitly bailed out.

Why be a sucker and contribute more now to pensions that will get topped up later? Why not contribute the smallest amount you can get away with?

Of course, there is a question as to when these bailout funds will run out, and what will be left for all those plans that did not get to the trough rapidly enough.

Apres moi, le deluge

Some are now taking this attitude:

Maybe high fantasy is not to your taste, and daytime TV is:

As we saw in my last post, Andrew Biggs brought forth the specter of a public pension bailout, which made me do a comparison — a public pension bailout would be about 20 times as big as this MEP bailout. [It’s actually 22 times, but who’s counting [me]]

Here’s an even more absurd suggestion: The hopeful news for Social Security buried in the $1.9 trillion bailout

Nobody’s noticed, but there may be a glimmer of hope for Social Security in the gigantic “rescue” package currently going through Congress.

Lawmakers have moved to include in the bill an unrelated $86 billion bailout for bankrupt union pension plans.

And once they’ve done that, it’s going to be even harder for them to argue that they shouldn’t bail out the stricken Social Security trust fund that is actually their responsibility. Social Security’s deficit: $16.8 trillion, or about $50,000 for every person in America.

[cough]

Dude.

Are you serious?

Now, reading the piece, maybe his editors cut out the parts where it made some sort of sense, because the bulk of the piece is how this bailout is an outrage. I totally agree.

You get bits like this:

Charles Blahous, an expert at George Mason University’s libertarian-leaning Mercatus Center, tells MarketWatch the bailout is not merely “irresponsible,” but “scandalous.” He accuses companies and unions of using accounting gimmicks to hide the problems for years, and warns that the new law won’t force them to stop, either.

This is absolutely true.

But this:

Given this, it’s going to be a much bigger scandal if Congress shafts Social Security beneficiaries harder than it does members of these union pensions. It would be ludicrous to hope that shame or embarrassment would constrain most politicians. But right now Social Security beneficiaries could be looking at a 25% benefit cut in just over a decade.

Joe Biden ran on a platform of protecting benefits, and actually raising them for many.

When the time comes for Congress to address the matter, they’d better give us the same terms as the unions, or we’re going to want to know the reason why.

Dude, the reason why will be very simple. IT’S IN YOUR FIRST THREE PARAGRAPHS.

We can’t bail ourselves out

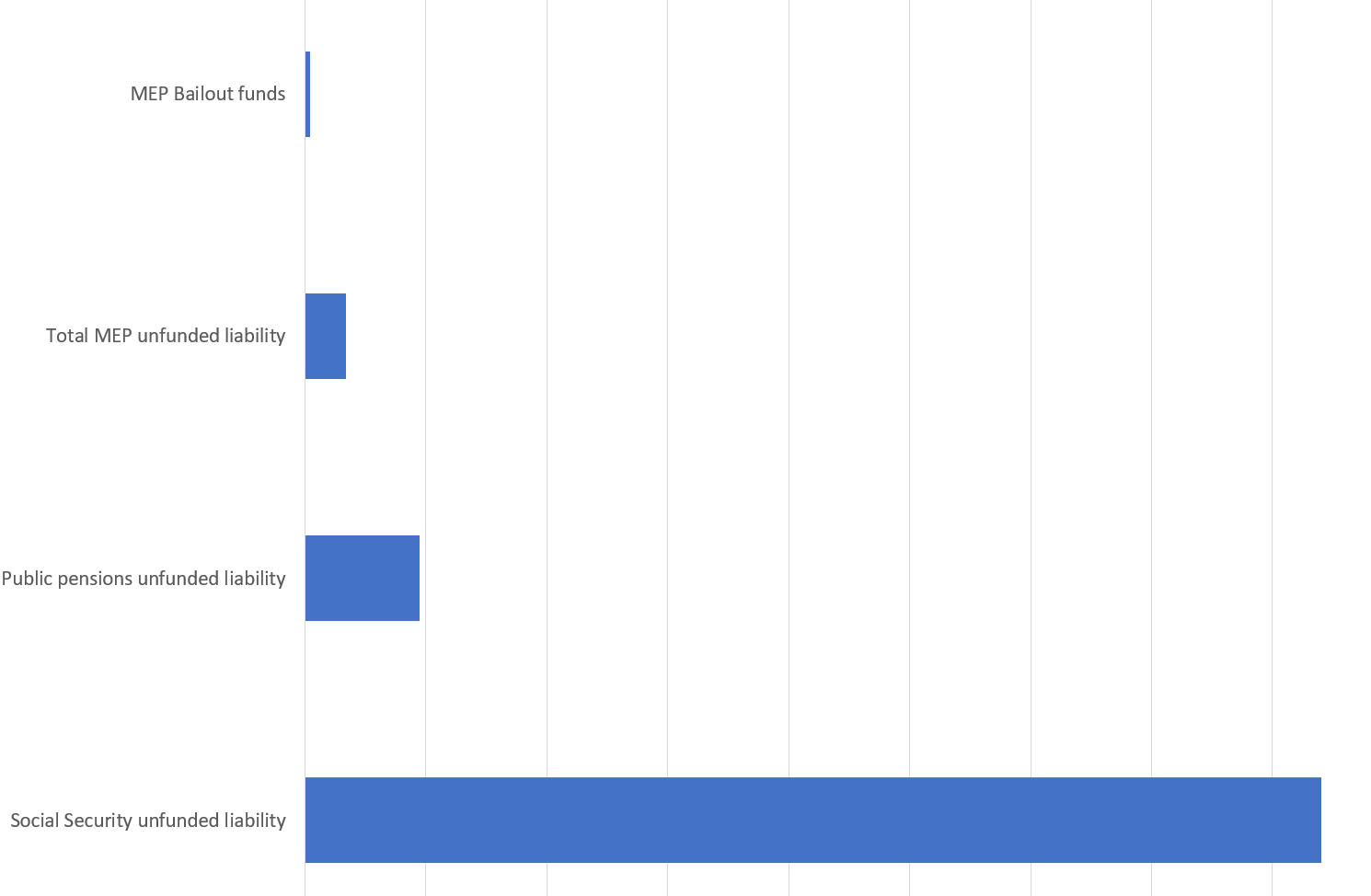

Let me make a comparison of four numbers:

- the MEP bailout size in the current bill ($86 billion)

- total MEP underfundedness ($673 billion)

- a theoretical public pension bailout ($1.9 trillion)

- a Social Security “bailout” amount ($16.8 trillion)

Here ya go:

Here are the whole-number ratios if you can’t eyeball the relationships above.

- The total MEP unfunded liability is 8 times that of the bailout bill amount

- The total public pension unfunded liability is 22 times that of the bailout bill amount (this happens to be the same as the total American Rescue Plan Act of 2021)

- The total Social Security shortfall is almost 200 times that of the MEP bailout bill

Now, there are loads of things that can be done with Social Security, and it wouldn’t even have to involve cutting benefits, but it definitely would involve taxing a bunch of people (and well beyond “the rich”) more. You can try out a bunch of different proposals yourself, many of which don’t involve benefit cuts at all.

We can’t bail out ourselves (look, don’t start with MMT on me or the magic money printer. I know about these. I’m talking reality.)

The future cannot bail us out. We tried that before, with the Boomers. The Boomers’ parents did fine – they produced enough people to make that sort of system work. But the Boomers produced far too little, in terms of the future.

Will anybody follow the money?

It will be interesting to see how fast the bailout funds run out for the MEPs.

John Bury looked up the stats on the Central States fund back in October 2020, and the unfunded liability for their 2019 report was about $44 billion.

Well, if Central States itself takes up over half of the bailout funds, that will be an eye-opener, eh? If anybody actually pays attention to the cash going out the door.

It is not clear to me what controls, if any, lie on the disbursements of this fund.

It says the funds are not to be commingled with other pension funds, but if the point is to cover benefit payments, can’t they just liquidate and pay out the benefits? It doesn’t matter if you require investment grade bonds as the investments these funds are put into if the bonds are just sold in the market for the cash to pay the benefits. They can adjust the rest of whatever assets they have to get the asset-liability mix they want…. there are no real strings attached to this money as far as I can see.

So, to those whose pension funds will get to belly up to the bar first, congratulations! It seems that you will get fully bailed out, and you probably don’t have to worry for a few decades!

For those who will eventually pay for this, whether through higher tax, higher inflation, or both … well, that’s what we get with a White House and Congress like this.

Related Posts

Taxing Tuesday: Trying to Escape Property Taxes, Follow-the-Leader, More Married Couple TCJA Scenarios

Taxing Tuesday: Income Tax for Chicago?

Theme for the Year: High Tax States Attempting to Avoid Effect of Federal Taxes