Mortality Monday: Huge Heroin Death Increases

by meep

So I have some depressing mortality stories I’ve had in draft for a while, waiting for sunnier days before I pushed go. Well it’s very sunny outside now, so here we go with the doom and gloom.

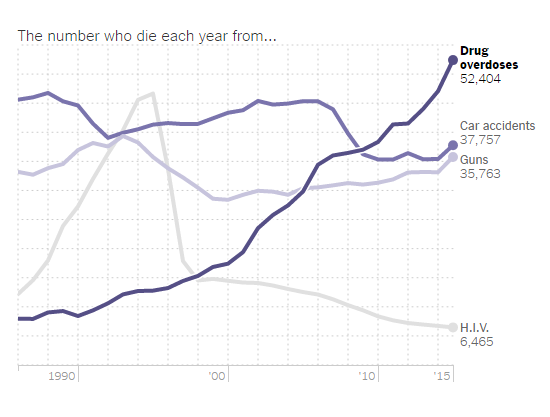

I had this one in draft for over a month, and it’s a good thing I waited. There’s a very good piece in the NY Times that ran recently, with excellent graphics. If you follow the link, you will find a number of graphs of numbers of deaths by cause: car accidents, guns, HIV/AIDS, and drug overdoses (excluding alcohol, I think.)

They give you the graph up to 1990, and ask you to complete the graph yourself, up to 2015.

(I’ll put my results at the end of this post, so you can see how off I was).

You should try the exercise yourself. The main reason for these “You Draw It” exercises with the graphs is to get you thinking about what you think the historical pattern was before it’s shown to you. That way the numbers become more real for you, no matter how far off you were. You get to think whether the pattern was or was not a surprise to you.

THE COMBINED COMPARISON

Here are the four causes, and the absolute counts:

They shortened the time range compared to what you will see at the bottom of this post, but the upshot is a huge increase in drug overdose deaths.

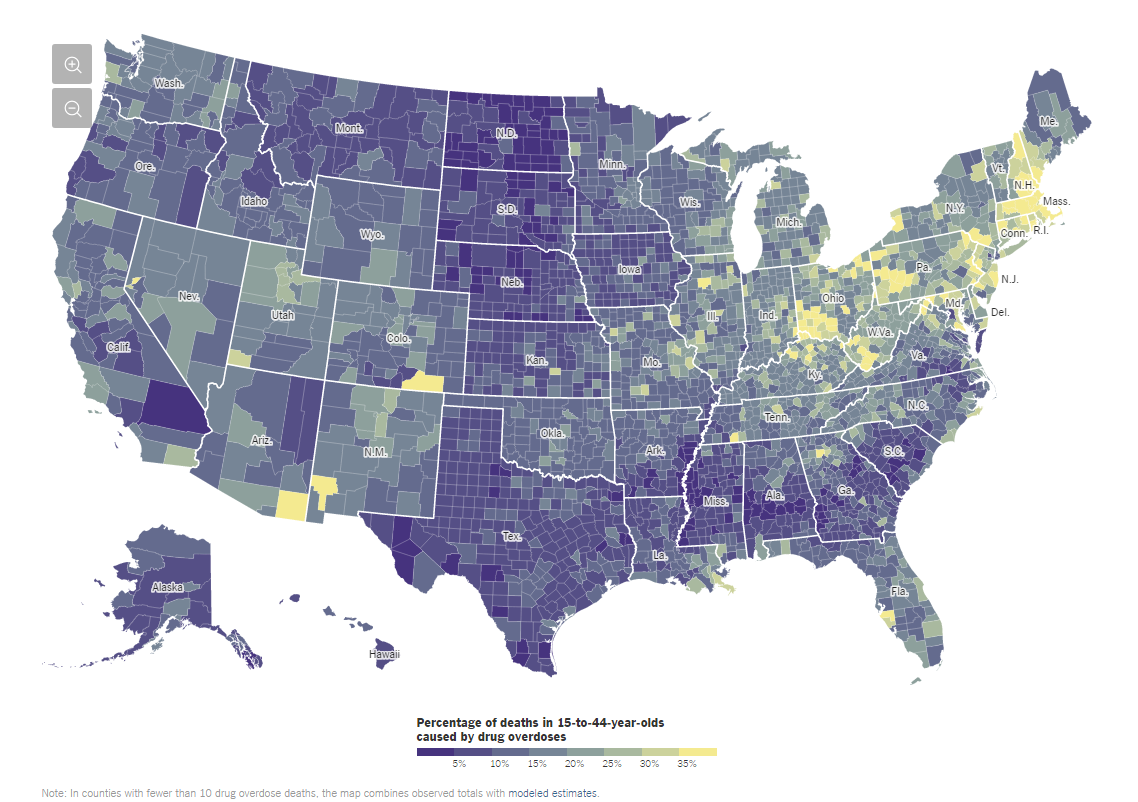

SOME MISLEADING GRAPHS

Before I get into the driving forces underlying the huge increase in drug overdose deaths, I want to point out a particularly misleading graph:

What are we looking at here? It’s called a Choropleth map, and what is being graphed is the percentage of deaths of those age 15 – 44 being due to drug overdoses. The more yellow = higher percentage; purpler = lower percentage.

But see, here is what is misleading: this gives you no idea if the rate of death due to drug overdose is really higher in those areas, because that’s not what you’re being shown.

I’ll give you an example: Tolland County, CT (where UConn main campus is) — 34% of deaths of those age 15 – 44 are due to drug overdoses.

Let’s compare to, say, Cook County, IL (where Chicago is) — 12% of deaths of those age 15 – 44 are due to drug overdoses.

Do I have to tell you that Cook County has a higher death rate in those ages than does Tolland County, CT?

There are a couple problems with the graph, period:

- Very few people die in ages 15 – 44. As I’ve shown before, more than 90% make it to age 50.

- Drug overdose (aka ‘poisoning’ – which does include alcohol, I think) is a top cause of death for younger folks… but far more for those age 25 – 44, than those 15 – 24

- Car accidents are far more likely to be a cause of death for teens, followed by suicide and homicide

- None of these have uniform incidence across the country, among sexes, races, etc.

- Oh, and it looks like the data underlying this came from 2007 – 2009… not exactly recent.

That said, the geographic component of drug overdose deaths may have something to do with what may be causing this increased fatality of drug overdoses: fentanyl.

INCREASED LETHALITY FROM FENTANYL

New Form of Drug Fentanyl Makes its Way to New York City

Authorities say a new form of the deadly drug fentanyl has made its way to New York City by way of China, exploiting a gap in drug laws.

Authorities said Wednesday 34 people, mostly Bloods gang members, were charged with distributing heroin, cocaine and furanyl fentanyl—a drug almost 50% more potent than heroin. New York Police Department chief of detectives Robert Boyce said it was the first time he had seen the new form of fentanyl in New York City.

While the drug is listed as a controlled substance under federal law, it isn’t covered by New York state law because of its slightly different chemical composition. Authorities said this could lead to a new trend of chemists abroad altering the drug to take advantage of the state laws.

Police recovered more than 8 kilos of narcotics, including 4.6 kilos of the furanyl fentanyl.

…..

Fentanyl has contributed to a record number of overdoses in New York City. City officials say an estimated 1,300 people died of drug overdoses in 2016, the highest total on record. About 1,075 of those overdoses involved an opioid. 90% of fatal opioid overdoses involved heroin or fentanyl.Furanyl fentanyl has cropped up in other U.S. communities, including Fargo, N.D., where the drug caused a number of overdoses last year. Fargo police say they believe some of that supply came from China.

A Wall Street Journal story last year detailed China’s growing role in shipping fentanyl compounds and their ingredients to North America, sometimes via Mexican cartels.

U.S. law-enforcement officials say loose regulation of the chemicals industry in China has allowed the trade to blossom, though Beijing has taken steps recently to crack down on it. Last month, at Washington’s urging, China said it would add furanyl fentanyl and three similar compounds to a list of controlled substances. The measure was set to take effect March 1.

This is one of the theories behind increased drug overdose numbers — not necessarily that opoid usage is up, but that people are getting drugs cut with fentanyl, which can have lethal consequences.

INCREASED OPIOID USE?

This one came to my attention a few years ago, when someone was giving a presentation on opioid use and the connection to Workers Comp Insurance costs.

Here is one such article –

In Illinois, opioid abuse hits insurance companies hard

We already know that opioid abuse presents a spiraling crisis across the U.S. President Trump is addressing the national issue at the White House today. Now, newly available data from private insurance claims shows just how much prescription pain reliever and heroin abuse has impacted Chicago and all of Illinois.

Private insurance claims related to opioid abuse and dependence diagnoses increased 329 percent in Illinois between 2007 and 2014, according to data from Fair Health, a New York-based nonprofit that seeks to increase transparency in health care costs.

In Chicago alone, such claims increased 382 percent over the seven-year period.

Robin Gelburd, president of Fair Health—which analyzed more than 23 billion claims from more than 150 million privately insured Americans—says that while Chicago’s claims increased at a greater rate than the state’s, the city’s proportion of opioid claims remains smaller than that of the rest of Illinois, based on population.

Citing U.S. Census data from last year, she says Chicago represents 21 percent of Illinois’ overall population but only 14 percent of opioid-related diagnoses.

This disparity between urban and rural abuse mirrors the situation in New York, where New York City comprises 43 percent of the state’s population, but only 13 percent of its opioid claims.

There are other possible explanations, Gelburd said, beyond the widely accepted notion that the opioid epidemic hits rural areas harder.

“It may be that more Chicagoans receive care under Medicaid” and therefore are outside the bounds of the Fair Health data set. Conversely, more Chicagoans may be high-income earners who pay for chemical dependence treatment out of pocket.

Chicago also saw the number of claims relating to heroin overdoses markedly fall between 2011 to 2012, and continue to decrease slightly in 2013 and 2014. The rest of Illinois, meanwhile, recorded a large increase in heroin overdoses between 2011 and 2012. They fell slightly the following year and remained level through 2014.

But while the city records proportionally fewer heroin overdoses, it has more than its share of diagnoses of “opioid abuse,” which is considered less serious than an “opioid dependence” diagnosis. (Opioid abuse may be diagnosed after a single incident of misusing prescription pain pills, according to Gelburd.) Between 2013 and 2014 alone, Chicago claims related to an opioid abuse determination skyrocketed 130 percent, while the rest of Illinois increased only 30 percent.

“The takeaway is that opioid abuse is a very serious issue, even if it’s not perceived to be as serious as dependence,” Gelburd said.

And here is something I heard about while driving home from class — Documents highlight Prince’s struggle with opioid addiction:

Before his death, Prince abused opioid pain pills, suffered withdrawal symptoms and received at least one opioid prescription under his bodyguard’s name, according to search warrants and affidavits unsealed Monday.

Prince was 57 when he was found alone and unresponsive in an elevator at Paisley Park on April 21. Nearly a year after his accidental overdose death at his suburban Minneapolis studio and estate, investigators still don’t know how he got the fentanyl that killed him. The newly unsealed documents give the clearest picture yet of Prince’s struggle with opioid painkillers.

BE CAREFUL OF THE TREND OF SMALL NUMBERS

The problem I’m running into is a bunch of stories that look something like this —

Heroin Deaths in Denver Up 933 Percent in 14 Years, Colorado Numbers Shocking:

In recent years, we’ve reported about concerns over heroin use in Denver, and statistics from over the past decade-plus, including provisional data for 2016, demonstrate that there’s definitely reason for worry. According to numbers assembled by the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, heroin-related fatalities in Denver have increased a staggering 933 percent since 2002.

The rise is nearly as steep on a statewide basis. During the past fifteen years, fatalities related to heroin in Colorado as a whole are up 756 percent, and they’ve kept escalating during the past three years even as heroin deaths in Denver have leveled off.

CDPHE provided the information to Westword under the auspices of Kirk Bol, manager of the agency’s registries and vital-statistics branch, as well as chair of its internal review board. When it comes to heroin, he describes the situation with straightforward simplicity. “Heroin use has gone up,” he says.

That’s definitely the case in recent Denver history. In 2001, the first year listed in the CDPHE’s report, there were no Mile High City deaths directly attributable to heroin: zero. (Statewide in 2001, 23 people died from heroin use.) This performance was actually repeated in 2004, and in general, as shown in the full statistics shared below, the fatality figures stayed in the single digits for the next five years.

Denver’s numbers have gone up considerably since then. In 2007, the CDPHE lists 12 heroin deaths in the city, with the number rising to 16 in 2008 — and the next year, 2009, the Denver fatality total doubled, to 32. Although the data moderated to some degree over the next four years, they soared to 35 in 2014, and they’ve remained over thirty ever since. The 2016 numbers aren’t officially in the books yet; final 2016 data should be available later in the spring. But the preliminary heroin-death figure for last year is 31.

31.

Well.

Okay, here we go. They give the numbers in the article for Denver & Colorado. Let me graph them.

Just in case you can’t tell: this is a bad trend.

But how many people died in Colorado in 2016? This article says about 605 people died in Colorado in 2016 from car accidents.

I partly wonder how much of the Colorado jump in deaths, specifically, is from a growing population. I know people in Denver bitching about the real estate prices due to a bunch of people moving in (which may or may not be related to marijuana legalization.)

The Denver numbers are hard to trend – there is so much variability. When you have a relatively small rate for a particular cause, all it takes is a few “excess” deaths to nudge the needle. The state death pattern seems more suggestive, because I doubt state population is growing that quickly… but again, these are relatively small numbers. Less than 200 deaths compared to about 35K deaths/year for the entire state.

That barely rounds up to 1% of deaths.

I am not trying to minimize these deaths, or even the trend. But some of these items aren’t helping figure out where the problem lies.

BACK TO THE GLOOM

I’m a very long-time subscriber to First Things, so this one made me sit up — AMERICAN CARNAGE

THE NEW LANDSCAPE OF OPIOID ADDICTION by Christopher Caldwell.

A few excerpts:

There have always been drug addicts in need of help, but the scale of the present wave of heroin and opioid abuse is unprecedented. Fifty-two thousand Americans died of overdoses in 2015—about four times as many as died from gun homicides and half again as many as died in car accidents. Pawtucket is a small place, and yet 5,400 addicts are members at Anchor. Six hundred visit every day. Rhode Island is a small place, too. It has just over a million people. One Brown University epidemiologist estimates that 20,000 of them are opioid addicts—2 percent of the population.

Salisbury, Massachusetts (pop. 8,000), was founded in 1638, and the opium crisis is the worst thing that has ever happened to it. The town lost one young person in the decade-long Vietnam War. It has lost fifteen to heroin in the last two years. Last summer, Huntington, West Virginia (pop. 49,000), saw twenty-eight overdoses in four hours. Episodes like these played a role in the decline in U.S. life expectancy in 2015. The death toll far eclipses those of all previous drug crises.

We have had some bad problems up here in Westchester County, too.

If you take too much heroin, your breathing slows until you die. Unfortunately, the drug sets an addictive trap that is sinister and subtle. It provides a euphoria—a feeling of contentment, simplification, and release—which users swear has no equal. Users quickly develop a tolerance, requiring higher and higher amounts to get the same effect. The dosage required to attain the feeling the user originally experienced rises until it is higher than the dosage that will kill him. An addict can get more or less “straight,” but approaching the euphoria he longs for requires walking up to the gates of death. If a heroin addict sees on the news that a user or two has died from an overly strong batch of heroin in some housing project somewhere, his first thought is, “Where is that? That’s the stuff I want.”

Tolerance ebbs as fast as it rises. The most dangerous day for a junkie is not the day he gets arrested, although the withdrawal symptoms—should he not receive medical treatment—are painful and embarrassing, and no picnic for his cellmate, either. But withdrawals are not generally life-threatening, as they are for a hardened alcoholic. The dangerous day comes when the addict is released, for the dosage he had taken comfortably until his arrest two weeks ago may now be enough to kill him.

…..

OxyContin was only the most commercially successful of many new opioids. At the time, the whole pharmaceutical industry was engaged in a lobbying and public relations effort to restore opioids to the average middle-class family’s pharmacopeia, where they had not been found since before World War I. The American Pain Foundation, which presented itself as an advocate for patients suffering chronic conditions, was revealed by the Washington Post in 2011 to have received 90 percent of its funding from medical companies.“Pain centers” were endowed. “Chronic pain” became a condition, not just a symptom. The American Pain Society led an advertising campaign calling pain the “fifth vital sign” (after pulse, respiration, blood pressure, and temperature). Certain doctors, notoriously the anesthesiologist Russell Portenoy of the Beth Israel Medical Center, called for more aggressive pain treatment. “We had to destigmatize these drugs,” he later told the Wall Street Journal. A whole generation of doctors was schooled in the new understanding of pain. Patients threatened malpractice suits against doctors who did not prescribe pain medications liberally, and gave them bad marks on the “patient satisfaction” surveys that, in some insurance programs, determine doctor compensation. Today, more than a third of Americans are prescribed painkillers every year.

Let me make this personal for a moment.

I suffer from chronic pain. Yes, the chronic pain is a symptom of a variety of things. I have tried a few drugs as prescribed by a neurologist, but the only ones that “worked” for my pain made it so that I couldn’t do anything, especially think.

I like thinking. It’s one of my favorite things. Heck, I can do it far more often than I can do my other favorite activities. Even eating has its limits.

Sometimes I go off and don’t blog, and sometimes it’s because one of my jobs and sometimes it’s because of the pain.

I don’t want to go down the opioid path because I’d rather be in pain than: 1. not being able to think or 2. be dead. (Yes, 2 is a proper subset of 1. Kinda.) There are aspects of my pain and dealing with it that may eventually kill me… just a lot slower than opioids would.

And I have had at least one relative die due to painkillers. So.

One more excerpt from the Caldwell piece — you should read the whole thing:

Residents of the upper-middle-class town of Marblehead, Massachusetts, were shocked in January when a beautiful twenty-four-year-old woman who had excelled at the local high school gave an interview to the New York Times in which she described her heroin addiction. They were perhaps more shocked by her description of the things she had done to get drugs. A week later, the police chief announced that the town had had twenty-six overdoses and four deaths in the past year. One of these, the son of a fireman, died over Labor Day. At the burial, a friend of the dead man overdosed and was rushed to the hospital. One fireman there said to a mourner that this was not uncommon: Sometimes, at the scene of an overdose, they will find a healthy- and alert-looking companion and bring him along to the hospital too, assuming he might be standing up only because the drug hasn’t hit him yet. In communities like this, concerns about “hurtful” words and stigma can seem beside the point.

Not talking is death.

THE ERRANT MEEP

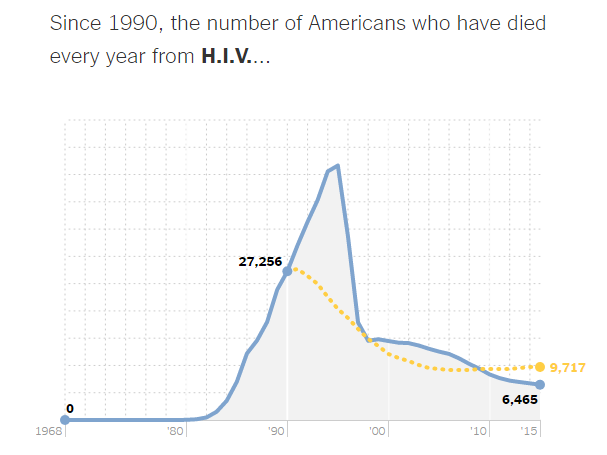

And here are my guesses for the NYT piece, that I got wrong. I will explain one of these wrong graphs another time, because the way actuaries generally think about deaths is not in absolute numbers.

The yellow dashed lines are my guesses, the blue lines are the historical stats.

Car accident fatalities:

Gun deaths:

(those are mostly suicides, btw)

HIV/AIDS:

(there is an interesting story involving that peak mortality and life insurance… but that’s for another day)

Drug overdoses:

So… yeah. Not that great. But how did you do?

Related Posts

Video: U.S. Mortality Trends 2020-2022 part 6: Heart Disease and Cancer

Mortality Monday: Memorial Day and the U.S. Civil War

A Sampling of Political Mortality