Puerto Rico Round-up: Trying to Determine How Bad It Is

by meep

As some facebook statuses say: it’s complicated.

As noted before, the leaders of Puerto Rico are trying to declare some form of bankruptcy to wipe out their debts. I did some immediate roundup of reactions, but this is a long haul issue.

So let’s try to total up the damage.

IMPACT ON PUERTO RICANS

Puerto Ricans Face ‘Sacrifice Everywhere’ on an Insolvent Island:

SAN JUAN, Puerto Rico — Angel González, a retired schoolteacher facing a 10 percent cut to his pension, is beginning to wonder whether his three-person household will have to cut back to one cellphone and take turns using it.

Santiago Domenech, a general contractor with $2 million of his savings tied up in bonds Puerto Rico just defaulted on, once had 450 employees. Now he has eight. His father-in-law, Alfredo Torres, owns Puerto Rico’s oldest bookstore, but it has been going downhill for two years.

“The government is bankrupt,” said Bernardo Rivera, 75, a private bus driver who sometimes earns only $40 all day. “Everyone is bankrupt. There is nothing left. People who do not have jobs do not take the bus to work.”

These are some of the voices of Puerto Rico’s business owners, retirees and public servants who are caught in the middle — they would say the bottom — of the largest local government insolvency in United States history. Faced with a $123 billion debt it cannot pay, Puerto Rico filed for a kind of bankruptcy protection on Wednesday, a move that sent shivers down the spines of everyone from bond holders fearful of staggering losses to street sweepers and public employees whose already meager paychecks are likely to dwindle.

…..

The government plans sweeping austerity measures in the coming months that will hit teachers especially hard. On Friday, Puerto Rico’s education secretary announced a proposal to close 184 schools. Teachers may see their hours trimmed by two days a month.So while the government seeks protection from lawsuits from the hedge funds and other financial firms that invested in Puerto Rico’s risky debt, residents of this United States territory are taking the squeeze. Fines for parking and other traffic violations have doubled. Dozens of government agencies are on the chopping block, while perks like the annual Christmas bonus and pay for unused sick time make for wistful memories.

On an island where household electric bills often reach hundreds of dollars, residents are worried that their future has been placed in the hands of strangers — an oversight board and a federal judge — who may or may not feel much empathy for American citizens whose per capita income is about $15,000 but who pay $6.25 for a gallon of milk and have an 11.5 percent sales tax.

…..

Gov. Ricardo A. Rosselló, who took office in January, acknowledged that low-income people without access to health care and parents with children in public schools would be the most vulnerable in the months ahead.“There has to be sacrifice everywhere,” he said in an interview. “We have been very clear about what that sacrifice is.”

His measures were deliberately spread out, so they do not hit any one group unfairly hard, he said. Although most residents believe Mr. Rosselló had no choice but to seek some sort of protection from the flurry of lawsuits that had already begun, others have criticized him for breaking a campaign promise. He is in the awkward position of being the son of one of the long line of former governors who brought Puerto Rico to its fiscal knees by borrowing and borrowing to balance budgets and to finance a bloated bureaucracy ripe with political patronage.

The last two administrations cut tens of thousands of positions from public payrolls, and now Mr. Rosselló has vowed to make “strategic cuts” that do not cause layoffs but put the government in a position to better negotiate with its creditors. Among the ideas is to cut government pensions by 10 percent, which will hurt retired police officers and teachers most, because they do not receive Social Security benefits.

It’s ugly. But as with other spendthrift and bankrupt governments, it’s not like money will appear magically from elsewhere to fulfill the overpromises made by profligate politicians.

WHERE DID THE MONEY GO?

Debt Island: How $74 Billion in Bonds Bankrupted Puerto Rico

Billions sunk into grand projects, expenses and bureaucracy

In San Juan, $2.25 billion bought a money-losing train lineSan Juan’s gleaming commuter train seemed like a coup — the kind of big-ticket item many U.S. cities can only dream of.

More than a decade on, the Tren Urbano is a monument to the folly, bloat and abuse that finally bankrupted Puerto Rico. Despite years of planning, it sells only a third of the rides it needs to, and loses roughly $50 million a year. The cost so far: $2.25 billion, $1 billion more than planned.

That, in a nutshell, is Puerto Rico’s story. With Wall Street’s help, the U.S. commonwealth borrowed tens of billions in the bond markets, only to squander much of it on grand projects, government bureaucracy, everyday expenses and worse. Debts were piled on debts, even as the economy gave way.

Long before the island’s government this month sought protection from creditors in America’s largest municipal insolvency, many on the island wondered where all the money was going. Officially, no one knows for sure: Puerto Rico hasn’t filed audited financial statements since its 2014 fiscal year.

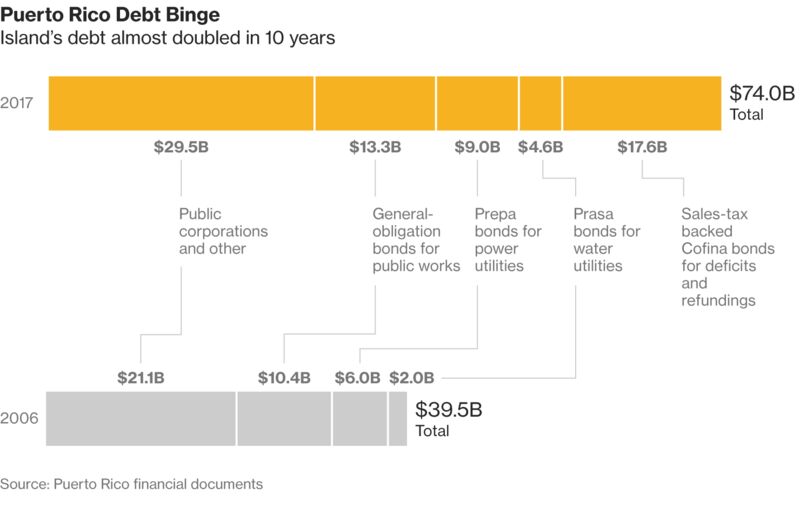

Over the past decade or so, bonds were issued by no fewer than 18 government entities, run by a merry-go-round of appointees that changed every four years when a new governor was elected. Bonds helped pay for schools and hospitals, public parks and government buildings, small-town baseball fields and modern stadiums. Bonds were sold to pay salaries, plug budget deficits and fund public pensions. Since 2006, the commonwealth’s outstanding debt has almost doubled.

…..

Blame is the one thing in surplus. In 1999, when Puerto Rico had an investment-grade credit rating, the island had roughly $16 billion of public debt. Today that figure is $74 billion and the rating is junk. The economy has contracted for a decade. Public debt as a percentage of total income was 100.7 percent in 2012, compared with 29 percent for New York, which has the highest ratio among the 50 states. Puerto Rico, where joblessness stands at 11.5 percent and half the 3.4 million inhabitants live in poverty, has become America’s Greece: Thousands of people, many of them professionals, are fleeing for the U.S. mainland.Puerto Rico’s borrowing was turbocharged because its debt is exempt from local, state and federal taxes everywhere in America. Mutual funds snapped up the bonds, which paid high yields because of their riskiness.

…..

Here’s a rough breakdown. More than $13 billion of general-obligation bonds backed by the commonwealth’s full faith and credit were supposed to finance public works like schools and hospitals.Roughly $17.6 billion of bonds backed by sales taxes covered budget deficits and replaced old debt with new. Almost $14 billion was issued by the water and electric utilities. And about $3 billion was sold to fund public pensions, though analysts estimate half of that went to cover current expenses instead.

If you’re giving a bunch of money to some big spender… and you don’t even know where it’s going? Or if you have a good chance of getting your money back?

Hmmm.

INTERLUDE

Here’s something to lighten things up:

This promo bit, Progress Island USA, is from 1973.

Those odd silhouettes and smartass comments are courtesy of MST3K, which has a new season on Netflix.

MUNI BOND MARKET

Puerto Rico Collapse Shows Debts Seen as Ironclad May Not Be

Island using emergency, bankruptcy-like powers given by U.S.

Territories, like states, were never allowed to use bankruptcyPuerto Rico’s decision to use a U.S. court to escape from its debts cast few ripples in the state and local bond market, where prices rose Wednesday. But the action — once inconceivable for a territory that didn’t have authority to file for bankruptcy — sets a precedent that could resonate with struggling states in the decades ahead.

The island was extended the bankruptcy-like powers by Congress as a way to end an intractable crisis, despite the assurance once given to investors that it couldn’t be done. While state finances are largely on the mend and officials have dismissed any suggestion they would ever push lawmakers for the same legal recourse, the path ceded to Puerto Rico has fostered speculation it may one day look attractive to governments at the end of their financial ropes.

“There’s a cautionary tale here across the board,” said Jim Millstein, founder of Millstein & Co., which served as financial adviser to Puerto Rico under former Governor Alejandro Garcia Padilla. “Municipal debt, state debt, federal debt, sovereign debt is not without risk. The truth is that bondholders get paid based on the health of the economy of the issuer.”

Puerto Rico’s restructuring will be the biggest in municipal-bond market history, vastly larger than Detroit’s $18 billion record bankruptcy, and will mark the first time a state-level issuer has had debt written off in federal court. It comes after years of borrowing to pay bills as the economy shrank and residents left for the U.S. mainland, leaving the government without enough revenue to repay what it owes.

…..

Municipal bankruptcies are rare, given that governments have the power to raise taxes to satisfy their debts. Even after the Great Recession, only a few local governments did so. And the scale of Puerto Rico’s debts is far larger than any other major American government, exceeded only by those of the more populated and wealthier New York, California and Massachusetts.…….

Nobody should assume that a Puerto Rico-type restructuring could be applied to U.S. states: Territories and states are distinct under the U.S. Constitution, and the Tenth Amendment limits the federal government’s ability to legislate for the states, according to lawyers and legal scholars.Virgin Islands

“If Congress acting under Article I powers were to amend the bankruptcy code to allow either voluntary or involuntary debt adjustment for U.S. states, very serious questions would be raised about unconstitutionality,” wrote Fordham University School of Law Professor Andrew Kent in a April 20, 2016 letter to the congressional committee that drafted Puerto Rico’s oversight law.

The events in Puerto Rico may have more immediate relevance to the U.S. Virgin Islands, its smaller Caribbean neighbor. Debt sold by the island is junk-rated, it faces population decline, large unfunded retirement liabilities and has a history of borrowing to fill budget gaps.

“If Puerto Rico can achieve this level of debt relief through Promesa as the initial plan suggested, it will only make sense for Virgin Islands to attempt the same,” said Matt Fabian, a partner with Municipal Market Analytics.

It’s so cute to see comments about unconstitutionality of bankruptcy processes for states, as if that’s the real problem.

I am no constitutional lawyer, philosopher, theorist or otherwise.

But not being able to declare bankruptcy has little to do with whether a government can default on bonds.

Without funds to honor bondholders’ suits

The government failed to include previsions in the fiscal plan in the event courts rule on higher payments for creditors

The government doesn’t have enough money to respond in case the bondholders’ suits prosper in court or if there’s a determination for higher payments to creditors than those contemplated in the fiscal plan.

The situation worsens because the special fund to pay for suits, which the government has kept for years, is also lacking the resources to address these contingencies.

“There are no previsions. The fiscal plan establishes the revenues we should reach in fiscal terms and the expenditures we must make and the service of the debt according to the resources available,” said Elías Sánchez Sifonte, representative of the governor of Ricardo Rosselló Nevares before the Oversight Board, when illustrating the government’s vulnerability to an adverse decision.

Sánchez Sifonte explained that the absence of contingencies or of a “plan B” is because the goal was always to reach agreement with bondholders where payments to creditors were reduced to make it possible to the money to reinvest it in the economy and fund the basic services offered by the government.

“(The fiscal plan) doesn’t contemplate any contingency in the event a suit should come down against the government because the objective was to reach a bona fide agreements, and that meant creating a payment program that would adjust to the Fiscal Plan. This will now have to be done under the Debt Adjustment Plan required under the Tittle III process,” said Sánchez Sifonte.

Currently, the government is burdened with defaults worth $3.2 billion, so it’s exposure to suits is greater. That figure is more than the consolidated budget of the Department of Education in one year. Therefore, to pay for that defaulted money, more drastic economic measures would have to be taken than closing the public education system for a year.

…..

The situation worsens because the special fund to pay for suits, which the government has kept for years, is also lacking the resources to address these contingencies.“There are no previsions. The fiscal plan establishes the revenues we should reach in fiscal terms and the expenditures we must make and the service of the debt according to the resources available,” said Elías Sánchez Sifonte, representative of the governor of Ricardo Rosselló Nevares before the Oversight Board, when illustrating the government’s vulnerability to an adverse decision.

Sánchez Sifonte explained that the absence of contingencies or of a “plan B” is because the goal was always to reach agreement with bondholders where payments to creditors were reduced to make it possible to the money to reinvest it in the economy and fund the basic services offered by the government.

“(The fiscal plan) doesn’t contemplate any contingency in the event a suit should come down against the government because the objective was to reach a bona fide agreements, and that meant creating a payment program that would adjust to the Fiscal Plan. This will now have to be done under the Debt Adjustment Plan required under the Tittle III process,” said Sánchez Sifonte.

Currently, the government is burdened with defaults worth $3.2 billion, so it’s exposure to suits is greater. That figure is more than the consolidated budget of the Department of Education in one year. Therefore, to pay for that defaulted money, more drastic economic measures would have to be taken than closing the public education system for a year.

Yes, I know there are errors in the English above. I just copy/paste.

That’s a bit of the reality. Sure, they can misspell “provision”. Snigger all you want, but spelling errors have little to say whether there’s any money to grab, even if a formal bankruptcy process is disallowed.

Puerto Rico’s Bankruptcy Fight Is About to Plunge Into the Unknown

Bondholders push competing claims but island may void them all

‘This is a government restructuring, not a court one’Dealing with Puerto Rico’s crushing debt has started to resemble a circular firing squad.

Simply put, the bankrupt island can’t pay everything it owes, so creditors are taking aim at each other as they squabble over who will get what’s left. But the debt’s size and the tangled process invented to rescue Puerto Rico mean there’s no established rule book to shape what comes next.

Holders of general-obligation debt have declared their right to be paid first, owners of sales-tax bonds are squabbling with one another over who deserves priority, and they’re all up against the commonwealth’s leaders, who want the cash for essential services. Amid this melee, Puerto Rico’s federal overseers will have to choose between paying U.S. hedge funds everything they’re owed or keeping schools, water and electricity running.

“There just isn’t enough money,” said Matt Fabian, a partner with Municipal Market Analytics Inc. in Concord, Massachusetts, who foresees a chaotic brew of lawsuits, federal interventions and politics. “Nobody has any idea what’s going to happen.”

All told, Puerto Rico has about $74 billion in debt and $49 billion in pension liabilities. Hedge funds holding $1.4 billion of general-obligation bonds, including Aurelius Capital Management and Monarch Alternative Capital, have already sued to get overdue principal and interest. On the other side, owners of $17 billion in sales-tax bonds, including Tilden Park Capital Management and GoldenTree Asset Management, have entered the fray. They’ll meet for the first time in court on May 17 in San Juan.

Default Notice

The dispute over the sales-tax bonds, named Cofinas after the agency that issued them, began in earnest May 4. That’s when the trustee, Bank of New York Mellon Corp., sent a notice of default to the authority that sold the bonds. The object was to keep the government from diverting the sales-tax revenue to other purposes before it pays what it owes to investors.

The New York-based bank acted after weeks of pressure from senior bond owners who urged the trustee to safeguard their claims. In the process, junior bondholders were irked because the default notice could mean no payments for them until the senior bondholders are paid in full. The notice sets a 30-day deadline for a response from Puerto Rico, which is supposed to pay about $256 million of principal and interest on Aug. 1, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

Puerto Rico’s status as a commonwealth means it’s not subject to traditional bankruptcy laws. Instead, the island filed for the next best thing to deflect claims, called Title III. It’s an in-court restructuring based on the U.S. bankruptcy code that was created under Puerto Rico’s Promesa law last year. But it’s never been used before, which means any cuts imposed by U.S. District Court Judge Laura Taylor Swain will be more likely to face years of appeals than a typical case.

Delayed Filing

Puerto Rico’s initial Title III filing on May 3 didn’t include Cofina. If it had, BNY Mellon may have been prohibited from sending its May 4 default notice. But the oversight and management board didn’t file its separate Title III action for Cofina until May 5, giving the bank a window to declare the default.

….

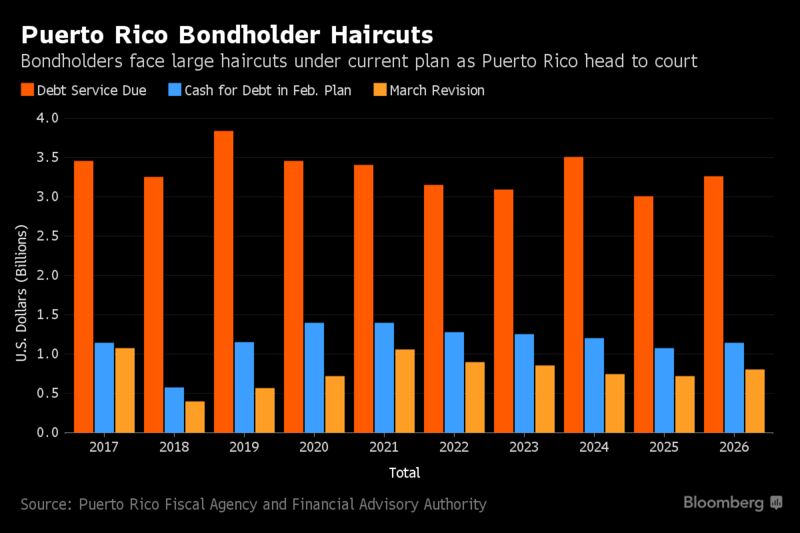

Debt DueFor investors, there’s a lot at stake. Cofina holders are owed more than $8 billion in debt service through 2026, with $704 million in payments due in the next fiscal year, which starts in July, according to the commonwealth’s fiscal plan.

…..

But because of the default notice, junior bondholders are unlikely to be paid, in order to safeguard claims of the senior Cofinas, said the people, who asked not to be identified discussing private transactions. Given the limited funds available for debt repayment, there’s a chance the subordinated holders could get little or no recovery. A representative for BNY Mellon declined to comment.What’s more, general-obligation bondholders claim that the entire Cofina structure violates the island’s constitution, and all the sales-tax revenue is owed to them. If the general-obligation claims are supported in court, all of the Cofina debt could be ruled invalid and investors could receive nothing at all.

People get into these constitutionality and legality arguments re: bankruptcy without thinking through whether all these beautiful words are really pertinent at all.

Reminds me of Bleak House by Dickens — there is a big estate case at the center, where various parties argue their merits for their particular side.

And in the end, only the lawyers got money. The estate was wasted away in the legal process.

Those were individuals, but it also stands for government. Because government is just particular bundling of individuals, just the same as for families. The scale may differ, but the essential reality is the same.

BOND MUTUAL FUNDS

Puerto Rico Menaces Mutual Funds That Resisted Market Exodus

OppenheimerFunds is top mutual fund holder with $6.3 billion

Mutual funds hold $15 billion of uninsured Puerto Rico debt

The biggest restructuring in the history of the U.S. municipal-bond market will fall heavily on hedge funds that wagered Puerto Rico wouldn’t go broke. But there’s plenty of little guys left holding the bag, too.More than two-dozen mutual funds hold about $15 billion of uninsured Puerto Rico bonds, about 20 percent of Puerto Rico’s $74 billion debt, according to the most recent data compiled by Bloomberg. While that’s less than what it was more than three years ago — before the island’s rating was cut to junk — the figures show that smaller investors who own mutual fund shares still have a significant stake, despite a buying spree by speculators who scooped up about a third of the government’s debt when others fled.

OppenheimerFunds Inc., a unit of Massachusetts Mutual Life Insurance Co., is the biggest mutual-fund holder with $6.3 billion. Franklin Resources Inc., the second-biggest, has about $3.1 billion. UBS Asset Managers of Puerto Rico funds hold $1.4 billion, followed by those run by Goldman Sachs Group Inc., which have about $1.2 billion.

Mutual funds bought the island’s debt because it offered high-yields and was exempt from taxes across the nation.

While those investments have been jeopardized by the island’s decision Wednesday to turn to a U.S. court to restructure its debt after a series of defaults, those mutual funds will likely see little immediate impact. The Caribbean territory’s crisis has been building for two years, giving funds plenty of time to pare their exposure. And the court filing — allowed under emergency legislation enacted by Congress last year — had little impact on bond prices, which had already tumbled. One of the island’s most active securities, general-obligation bonds that were first sold for 93 cents on the dollar in 2014, traded for 64 cents Friday.

The variety of bond holders, however, underscores the broad reach of the commonwealth’s crisis, which will be sorted out under the supervision of U.S. District Judge Laura Taylor Swain after it proved too vast for the government to do out of court. Puerto Rico has issued many different classes of debt backed by different revenue sources: general revenue, sales taxes, utility fees — even rum-tax money.

While analysts say it’s impossible to gauge exactly how much of their money various bondholders will get back, they won’t be totally wiped out. Before seeking out court protection, Puerto Rico offered general-obligation bondholders at least 70 cents on the dollar, with the possibility for 20 cents more if the island’s finances rebound.

Despite its stake in Puerto Rico, OppenheimerFunds’ Rochester High Yield Municipal Fund is the top-performing municipal fund over the last three years, returning 8.3 percent annualized, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. The $5.8 billion fund is a large holder of junk-rated tobacco bonds, which returned an annual 11.3% in the three years ending March 31, according to the S&P Municipal Bond Tobacco Index.

How Big Are Mutual Funds’ Puerto Rico Losses? $5.4 Billion

The losses from soured investments in Puerto Rico bonds are coming into focus for some of the world’s biggest mutual funds, and it is a brutal reckoning.

The total red ink for mutual funds that invested in debt issued by the troubled island commonwealth is as much as $5.4 billion over the past five years, according to a Wall Street Journal analysis of mutual-fund holdings and municipal-bond trades.

Those losses, which are both actual and on paper, were tucked inside a wide range of funds managed by Franklin Resources Inc., OppenheimerFunds Inc., Vanguard Group, Goldman Sachs Asset Management, Western Asset Management Co., Lord, Abbett & Co., AllianceBernstein Holding LP and Dreyfus Corp., which is part of BNY Mellon Investment Management.

The damage done to mutual-fund bets is one reason why a court-supervised restructuring of Puerto Rico’s debt that starts this week with a hearing in San Juan is expected to become such a lengthy battle. A diverse group of creditors will be competing for a limited pot of money, and allocating Puerto Rico’s resources will be complex because of the competing interests at stake.

Many mutual-fund firms have greater incentive to agitate for maximum recovery — and have greater potential for losses — because they purchased debt closer to par values. Mutual funds as a group still hold about $14.6 billion of Puerto Rico’s $73 billion in outstanding bonds after selling off more than $9 billion over the past five years,according to research firm Morningstar Inc.

Franklin and Oppenheimer hold most of the mutual-fund debt, according to Morningstar. Oppenheimer’s paper and actual losses are as much as $2.1 billion, and Franklin’s are as much as $1.6 billion, according to the Journal’s analysis. Franklin has $741 billion in assets under management, while Oppenheimer has $230 billion.

…..

Guy Davidson, director of municipal investments at AllianceBernstein Holding, said he is relieved the firm sold off most of its Puerto Rico debt in 2014. “No matter how you cut it, Puerto Rico’s been a bad investment for most investors,” he said.For mutual funds, Puerto Rico’s debt has long had a special appeal because the bonds are tax-exempt nationwide. Most municipal bonds are exempt from state taxes only in the state they are issued. The commonwealth’s ballooning debt load appealed to state-specific mutual funds in places where local government bonds were scarce or expensive.

About 45% of the Puerto Rico debt mutual funds currently hold is in funds designated by Morningstar as single-state funds.

When Puerto Rico last tapped the bond market in March 2014, offering 8% interest, underwriters were flooded with orders from hedge funds and mutual funds for the junk-rated debt. Twenty mutual-fund families bought a combined $263 million that quarter, according to Morningstar data.

Most funds that stocked up on the island’s debt before prices began to slide have fallen behind their benchmarks, according to the Journal’s analysis. That includes 13 of 15 funds that had at least 15% of their assets in uninsured Puerto Rico bonds in the first quarter of 2013. Most of these are single-state funds spanning the U.S., from New York to Arizona. Two of those lagging funds closed in 2013 and 2016.

How much mutual funds and other creditors in Puerto Rico get back will depend in large part on which securities they own. For example, general-obligation bonds carry some of the commonwealth’s strongest legal pledges, and holders of those bonds may fare better than many other investors.

So…yes. There are risks in mutual funds.

I hope this is not news for anybody reading this.

OTHER COMMENTS

Perils in Puerto Rico: Is Bankruptcy the Answer?

In Spanish, Puerto Rico translates into “rich port.” The meaning of the name took an ironic turn last week when the U.S. territory requested that it enter a new form of bankruptcy protection, burdened by $123 billion in debt and unfunded pension commitments. Puerto Rico’s hopes for redemption lie in a 10-year fiscal plan drafted by a federal oversight board that aims for broad-based structural and economic reforms.

The cornerstone of the plan is debt restructuring and spending cuts, which is key to restoring Wall Street’s confidence in the commonwealth and protecting its future borrowing power in the capital markets, according to David Skeel, professor of corporate law at the University of Pennsylvania Law School, who was one of seven people on the Financial Oversight and Management Board for Puerto Rico that gave the commonwealth the green light to enter the debt restructuring process.

Skeel says many factors led to Puerto Rico’s current economic distress, including the phasing out of a big tax benefit the territory was receiving in 2006. “Rather than ratcheting back on what it was spending, it increasingly financed its operations with debt, which is always a problem,” he said. “You put that together with a number of factors and you end up with $123 billion of debt, if you include unfunded pensions.” Moreover, the $6.4 billion block grant that Puerto Rico received from Obamacare is rapidly running out, Skeel says. Currently, he adds, Congress has set aside $295 million for Puerto Rico this fiscal year.

…..

Rosario Rivera-Negron, economics professor at the University of Puerto Rico at Cayey, traced the territory’s problems to the “collapse” of its economic model since 1974 and the underwhelming economic growth that followed in subsequent decades. “Eventually that was going to blow up in our faces, and that is what happened,” she said. She recalled issuing that warning two years ago. Puerto Rico needs “new institutions, new structures, new laws and new incentives,” she told Knowledge@Wharton in 2015.…..

Tracing the Decline“Rich-country policies are imposed on developing country settings without any regard to the consequences,” Rivera-Negron said of how Puerto Rico was hurt by U.S. policies. In 1938, the U.S. extended its minimum wage requirements to Puerto Rico but lowered it in later decades when the territory found it too expensive, but ratcheted that back up to U.S. levels in 1974, along with tax breaks for businesses soon thereafter. Those minimum-wage requirements boosted earnings for workers but generated high levels of unemployment as companies laid off people, prompting government subsidy programs. Then tax breaks were withdrawn in 2006, triggering a long recession. Skeel points out that the territory’s unemployment rate exceeds 12% and 46% of its people are under the federal poverty level.

Few people in the political class know how to successfully fix Puerto Rico’s problems, and those who do hold themselves back because they have to take politically unpopular measures, said Sotomayor. “They have refused time and again to address the problems [such as] balancing the budget and, implementing economic reforms, even when the retirement systems are about to go bankrupt,” he said. “We are passive and have become accustomed to have others solve our problems,” he added, referring to policies drafted in Washington.

Again, getting caught up in process issues, without considering whether there is any actual money to fulfill all promises.

Nobody knows how to fix PR’s problems partly because they don’t want to admit: no, they can’t be spending as much money as they have been for a decade or more.

Again, if it were an individual, you’d be able to say something like “No, you can’t be building yourself a mansion and buying a Mercedes on a barista income”. But because it’s government, people think there’s some sort of magic that can fix that.

STATEHOOD AS FIX?

Amid Puerto Rico’s Fiscal Ruins, a New Push for Statehood

SAN JUAN, P.R. — It is a proudly Spanish-speaking territory at a time when the White House has taken down the Spanish version of its website. It is as materially poor as it is culturally rich. And Puerto Rico has entered a new and exotic version of bankruptcy, facing a staggering $123 billion in debt and pension obligations.

In short, it is difficult to imagine a worse time for governing-party officials in this struggling Caribbean commonwealth to persuade Washington it is ready to become the 51st American state.

But they have pledged to make their case anyway.

Tell them that it seems impossible, and they will conjure the long moral arc of the universe and how it bends toward Puerto Rican statehood. “That’s what they told the blacks,” an indignant Ramón Rosario Cortés, Puerto Rico’s public affairs secretary, said in an interview last week. “That they were wasting their time attending the marches of Martin Luther King Jr. because nobody was ever going to hear the cry of the people!”

A vigorous push for statehood was a central campaign promise of Gov. Ricardo Rosselló, 38, who was inaugurated in January. Next month, he will ask residents to vote, in a nonbinding referendum, for statehood as part of a long-term fix for a commonwealth facing a period of severe austerity that is likely to include shuttered public schools, frozen salaries, slashed pensions and crimped investments in public health. The island remains in the grip of a recession that has lingered for much of the past decade.

Statehood, Mr. Rosselló and his allies argue, would mean more investment in infrastructure, which would attract more businesses and create a more stable economy. Mr. Rosselló has also criticized Puerto Rico’s current relationship with the mainland as a “colonial status” that deprives its 3.4 million residents “of the right to political, social and economic equality under the U.S. flag.”

But Mr. Rosselló must not simply convince a wary Congress, which, by law, holds the key to Puerto Rico’s relationship with the United States. On the island, the “status” issue, as it is typically called, has for decades been the defining — and most divisive — question at the heart of Puerto Rican politics.

The three main political parties are not really divided along ideological lines; rather, Puerto Ricans know them as the party of statehood, the party of independence and the party that supports some improved version of the status quo. Voters in the June 11 referendum will be asked to choose among those three visions, and Mr. Rosselló’s allies are making a big push.

…..

During the Cold War era, the F.B.I. tried to undermine the independence movement here, but it has also been weakened by the perks of commonwealth status. Though Puerto Ricans residing on the island do not vote for president, and their sole representative in Congress cannot cast a vote, they are United States citizens and may move to the mainland as they please.It is an option Puerto Ricans have increasingly taken advantage of in their effort to escape the economic malaise on the island, where 46 percent of the people are in poverty and the unemployment rate was 11.5 percent in March. More than 400,000 have moved to the mainland in the past decade. As of 2013, there were 5.1 million Puerto Ricans living on the mainland, according to the Pew Research Center, while the number of residents in the commonwealth is expected to dip below 3 million by 2050.

The middle ground has long been occupied by the Popular Democratic Party. Its leaders do not want to abandon the autonomy that the current status provides, but they argue that serious changes are needed if the island’s economy is to be saved.

…..

The crisis has driven some Puerto Ricans into Mr. Rosselló’s camp. Erick Storer, 36, became a convert to the statehood movement when he was laid off three months ago from his job in the pharmaceutical industry. The sector had thrived here thanks to generous corporate tax breaks created by Congress in 1976.But Congress began phasing out the breaks in 1996, and they disappeared in 2006 — one reason, experts say, the economy has taken such a hit. With no representation in Congress, residents like Mr. Storer have been left feeling as if they have little say in policy making.

…..

Others warn that statehood will not be a panacea. Among other things, Puerto Ricans would have to give up their current exemption from federal income tax for income earned in the commonwealth.

Statehood would not fix their fiscal troubles. Ask Illinois, Kentucky, New Jersey, California, etc. about that.

But perhaps statehood would make people take the situation a bit more seriously. As a state, they know they’d be getting no bailout. As a semi-dependent territory, it can set up the expectation that perhaps the feds will take care of everything, no matter how many times the feds say “No, it’s your problem.”

But then, it does seem that various mainland entities think they’ll get bailed out by the feds.

Good luck to all on that.

Related Posts

Public Finance: Guys, It's Not Really a Competition as to Who is the Worst

Not With a Bang, But a Whimper: Demographic Decline Undermines Public Finance

More Soda Tax Idiocy: This Time, It's Seattle