A Fisking of Yet Another Public Pension "Explainer" and a Closer Look at Texas ERS

by meep

Thanks to Bill Bergman of Truth in Accounting for pointing me in this direction… because it started in a particular place I am all too familiar with and ended up somewhere I wasn’t expecting.

So come on this ride with me.

[note: not in the order of the ride-taking… if you think I get tortuous in digressions on the blog, you should see my browser history.]

Pension “truths” are in the eye of the beholder

Ah, Protect Our Pensions, a group that totally misses what people like me are trying to say [to wit: the standard-operating-procedure for designing, valuing, and funding DB public pensions does not protect them at all, but makes them fragile].

Let’s see what they’re serving up this time!

THREE TRUTHS AGAINST TRUTH IN ACCOUNTING’S ATTACKS ON PUBLIC PENSIONS

The following is written by Tristan Fitzpatrick, who is a media guy and posts most (all?) of the items on the Protect Our Pensions blog.

Let’s check these three “truths”.

Number 1:

1. Unfunded liabilities are drastically taken out of context.

I totally agree, they are often taken drastically out of context in media coverage of pensions! The “It’s something only if everybody retires tomorrow!” kind of lie often comes from a place of deep ignorance, but often it is somebody who knows that the measured unfunded liabilities are of the benefits already earned AND a present value of said benefits…. both of which are likely going to be a lot less than the dollar amounts projected. So, no, it’s not everybody retiring tomorrow.

But sorry, I interrupted Tristan. Let’s see what he wrote.

Truth in Accounting goes to great lengths to exaggerate the unfunded liabilities of pension plans. The organization mentions a state’s overall unfunded pension liabilities in a single year while failing to highlight the bigger picture, which is that pension plans are specifically designed to be invested in the long-term.

An unfunded liability is similar to a 30-year mortgage in that banks and credit agencies understand that each is meant to be paid off over a determined period of time, not all at once. As we’ve noted before, with an unfunded liability, “the system never needs all that money at one time.” For a public employee who will retire in 20 years, for example, their plan will have that same amount of time to earn investment returns to pay out benefits in retirement. Using unfunded liabilities to rank each state’s fiscal effectiveness in a given year, then, is highly misleading.

OH DEAR GOD SAVE US FROM INNUMERATES.

I mean, ahem. Sorry.

Maybe you’re just deeply ignorant, Tristan. After all, you’re surrounded by people who think it’s just fine to discount at 8%.

Bad metaphors/analogies for very large obligations

To save some time, let us look at my old post on the meaning of funded ratios:

So what does the funded ratio mean?

It’s a particular measure comparing the assets you have on hand with the accrued liabilities at a particular point in time. It’s a simple fraction, assets over liabilities.

One of the AO users described it as “the ratio of current assets to the portion of future benefits attributed to past service”.

I will get into this a little bit, because the AO user didn’t mention “actuarial present value”… but I want you to note: “attributed to past service” — these are the benefits the worker has already earned. Not earned 20 years from now. Earned in the past.

In no actuarial method that I know of do we assume that everybody is going to retire tomorrow in setting the value of that liability. There is a set of assumptions, one of which is the distribution of ages at which people will retire.

Now, those assumptions can be wrong, but nobody uses the “everybody retires tomorrow” assumption unless something really bizarre is happening.

[By the way, this year “something really bizarre is happening”, and some police and teacher systems have been showing much higher retirement rates than usual. This will likely lead to “actuarial losses”, which is beyond the scope of this blog post.]

It’s not quite the same, but it would be equivalent to “everybody dies tomorrow” assumption for an actuary valuing life insurance reserves or “everybody is in a car accident tomorrow” for an actuary setting personal auto reserves. It’s absurd… and would make the funded ratio look much, much worse.

Even during the COVID crisis, nobody is assuming everybody dies tomorrow (and if everybody did die tomorrow, the life insurance companies would have nothing to worry about. Think about it.)

In addition, no, pensions aren’t like a mortgage:

I’m a bit tired of the mortgage metaphor everybody uses, because it’s a bad metaphor.

When you mortgage a house, you’re buying an asset at a point in time, but you’re going to be using it over a number of years. So you try to finance it over a reasonable amount of time, and it’s paid like a sinking fund. The principal balance reduces through the life of the mortgage.

But pension liabilities aren’t capital assets like a house. The accrue as benefits for services rendered in particular years. If you’re thinking of mortgages, it’s like you started putting the payments for cleaning services of your house on your mortgage.

Yes, some people have put short-term operating expenses (as opposed to capital expenditures) on things like mortgages and HELOCs. THIS IS A BAD IDEA. DON’T DO IT.

A better metaphor is that of the credit card balance.

And in that 2017 post, I link to an even older post in which I explain the public pension unfunded liabilities are like a credit card balance:

But pensions aren’t a capital asset/expense. They’re an operational expense. They are for paying for current service by giving some money in the future, but the expense is incurred right now.

Just like when I go out to a fancy restaurant and put that tab on my credit card. I usually pay off my balance in full each month for credit cards, because I use them to pay for my current, operational expenses like groceries, the energy bill, my Amazon habit. If all I did was keep charging operational expenses to my credit cards and not paying off the balance, I’d be accruing debt like the unfunded liability in public pensions. The credit cards don’t expect me to pay off all the balance all at once, but I don’t need to be still paying for today’s meal at Per Se for the next thirty years.

Oh wow, the old days of going to a Manhattan restaurant… ah.

But to get back to his point: no, the unfunded liabilities don’t need to be made up all in one year — after all, it usually took decades for them to get so large.

But there is a tipping point past which you cannot fill that hole.

When there aren’t enough assets in the fund to cover those already retired, where there aren’t any putative decades to make up for those holes… then no, you’re out of time to be making up that hole. (Illinois and New Jersey are in this bucket, even with high discount rates.)

And as for plans where they at least have the retired folks covered, remember that active worker, each year, is accruing more in pension promises. Are the contributions keeping up with that?

Back to the blog: many questionable claims

But let us see how Tristan finishes truth 1:

In a select few states, lawmakers have repeatedly skipped or deferred their required contributions to the pension system, despite public employees paying their fair share with every paycheck.

This will make their overall unfunded liabilities seem larger because there isn’t enough money invested to earn optimal investment returns.

They also miss out on down years… winning! You can’t lose on investments if you didn’t have the money in the investments in the first place….

Skipping or deferring contributions can also threaten a state’s credit rating (making it more expensive to fund future projects).

Yes, absolutely true!

[Still waiting on Illinois to move to junk, though]

The vast majority of pension plans, however, are well-funded,

and it’s not too late for leaders in those few states to reverse course and practice fiscal discipline to meet their plan’s obligations and to maintain their state’s credit rating.

I would put citation needed here (it’s pretty much too late for New Jersey and Illinois… maybe for Connecticut and Kentucky, too. We’ll see.)

But I do agree most of the states and localities really can get back on track in a variety of ways, and get their public pension plans to full-funding, especially via a risk-sharing plan like Wisconsin has.

And that was just the first “truth”.

Rounding out the pension truths

Let’s check on the next:

2. Pensions make up little of a state’s overall budget.

It really depends on which state you’re talking about…. and whether they actually made full contributions. Then, there’s the case where pension costs, such as with Calpers, are being paid by localities, not the states.

3. Public pensions are a benefit to taxpayers.

Yeah, I could put in citation needed, but a link is given… and it’s the same “We can use the taxpayers’ money more efficiently than they do!” bullshit.

“Look at all the stuff these pensioners spend their money on!”

“But that money was with other people… are you saying that they would shove that money into a hole in the ground if you didn’t make them give it to the state for pensions?”

“Uh… yeah! That’s what those taxpayers would do! Damn taxpayers!”

Mmmmm

Unique definition of “actuarial soundness”

That wasn’t the only blog item at the site to catch my eye.

TEXAS STANDS UP TO TRUTH IN ACCOUNTING

Don’t mess with Texas, Truth in Accounting! Take that!

There are various things in this piece… some of which are entirely true, and some of which made me stop in my tracks.

Here is something from the latter category.

By our own state law, a pension is actuarially sound when it has an amortization period below 31 years.

That is quite the definition.

[Someone once told me, by the way, that you’re not allowed to have an amortization period of higher than 30 years due to GASB, currently. I am not a government accountant, and I’m not going to check. You can find out if that is true. In an old doc I found, amortization periods up to 40 years were permissible.]

When I read crap like that, it reminds me of Humpty Dumpty in the Alice books:

“I don’t know what you mean by ‘glory,’” Alice said.

Humpty Dumpty smiled contemptuously. “Of course you don’t—-till I tell you. I meant ‘there’s a nice knock-down argument for you!’”

“But glory’ doesn’t mean ‘a nice knock-down argument,’” Alice objected.

“When I use a word,” Humpty Dumpty said, in rather a scornful tone, “it means just what I choose it to mean—-neither more nor less.”

“The question is,” said Alice, “whether you can make words mean so many different things.”

“The question is,” said Humpty Dumpty, “Which is to be master—-that’s all.”

Well, you can define it as actuarially sound that way, but it doesn’t make a pension benefit design or funding plan sustainable.

I can think of insane methods of amortizing a pension liability, and I don’t even need to use my glorious imagination for it, because I have two nutty ideas from real life.

It’s easy to make the math “work out” over 30 years, as you can see with those ridiculous ramps that were never going to get paid in Illinois or Connecticut. Was that actuarially sound?

Sure, if words have no meaning.

The term “actuarially sound” has been controversial within the actuarial profession itself over multiple fields, not just pensions. Here is a report from 2012, from the American Academy of Actuaries, detailing how the term is (or isn’t) used in a variety of contexts.

Actuarial Standard of Practice #1 has this note:

The phrase “actuarial soundness” has different meanings in different contexts and might be dictated or imposed by an outside entity. In rendering actuarial services, if the actuary identifies the process or result as “actuarially sound,” the actuary should define the meaning of “actuarially sound” in that context.

Also, I looked up Keegan Shepherd, the author of this piece – he is a historian by training, and not an actuary. I will just say he doesn’t know what actuarial soundness is supposed to mean, other than a mere assertion.

Put another way: there is no repo man or bill collector who is going door to door to collect on our pensions’ unfunded liabilities. You are not going to get a call to pay up. You are not going to get a bill for $11,000. You are not going to have your car taken as collateral because, quite simply, that’s not how unfunded liabilities work. You, as a taxpayer, are not going to pony up some enormous amount of money out of the blue.

Oh dear Lord, not this bullshit again. “We don’t have to pay it all at once!”

No, you don’t. And the measurement takes that into account.

What does eventually happen is that required contributions get larger and larger, until the sponsor can no longer cover them. So then the pension fund starts getting short-changed and its funded status slips. Then it gets to a point where it’s in an asset death spiral until all the funds are gone. The liability cash flows aren’t being supported.

And you can’t pay enough cash to cover those benefits (otherwise, you wouldn’t have been in that asset death spiral).

That said, he does make a good point with respect to Texas pensions:

When unfunded liabilities do continue to grow, it’s legislators’ responsibility to act early. In the case of our Employees Retirement System, the unfunded liability is the size it is precisely because legislators refused to act early to restore the system to full health. This has only made the problem more expensive to fix, and unless they act during the next legislative session, that unfunded liability will only continue to grow.

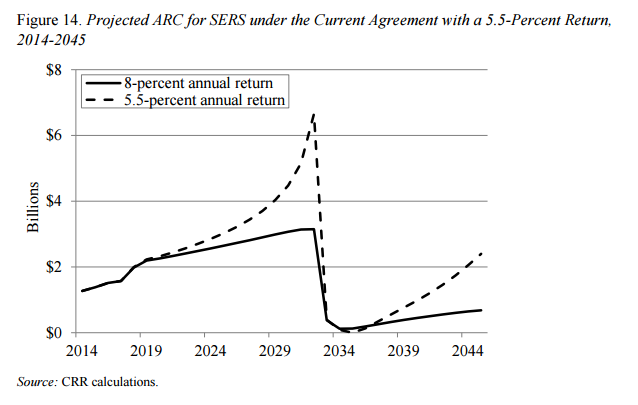

Let’s take a look at Texas ERS, and you will see the problem.

A look at Texas ERS: Contributions, Funded Ratios, and Assets

Let’s take a quick peek at Texas ERS, which was 70% funded in FY2019. What’s this? They used to be fully-funded last in 2002, and they’ve just been slipping, slipping slipping? I wonder why that might be?

Could it be…. underpayments to the pensions?

Yeah, that’s not a good look, but I do note the percentage of payroll for required contributions really isn’t that high compared to other public plans. One of the problems is the Texas legislature meets only every other year, and there’s an obvious lag between what the legislature approves to contribute and what the actuaries calculate. This is not good governance for pension funding.

Or maybe the investments are also underperforming:

The 5-year average isn’t too different, and the 10-year average is decent, if a little underperforming (a fund making 9.6%/year for 10 years makes 14% more in accumulation than one earning 8.2%/year, which isn’t a huge difference.)

But maybe they’ve changed their allocation recently….

HOLY CRAP THOSE ALTS [the yellow line]

30% MISCELLANEOUS ALTS? WHAT….

Um, Texas, we need to talk.

Don’t go chasing waterfalls

I had a whole series on public pensions getting into trouble by investing in “alternative” asset classes. There is nothing intrinsically bad about these assets, but they can be really tricky to properly manage, and many very shady and inappropriate people are operating in this space.

The crazy part is, I was looking at that page at the same time I was catching up with industry news. And I saw this:

ai-CIO: Texas Employees CIO Tom Tull to Retire

He built out alternatives at the $29 billion retirement system soon after joining.

If you look at that graph, Tull had to have been at the fund for only a short time, if he is responsible for that ramp-up.

Let us posit that Tull really knew what he was doing… will it go well after he retires?

Tom Tull, the investment chief at the Employees Retirement System of Texas (ERS), will retire next summer after leading the $29 billion pension fund for eight years.

…..

In 2009, Tull joined the fund after the executive director at the time sought to bring someone with a fresh perspective to the team. Tull, who worked for decades in the private sector, already had spent 11 years advising the ERS pension board. His first role at the fund was as director of strategic research, which he used to energize the hedge fund program.After he took over as chief investment officer in 2012, he continued to build up an allocation to alternatives, such as private equity, private real estate, and hedge funds. Today, the fund holds a 31% allocation in alternatives, up from 26% in 2017. ERS plans to increase that allocation to 34% longer-term.

Oh my head.

Several factors propelled the fund’s tilt toward alternatives, Tull said: an increasing number of opportunities the investment team was spotting from inefficiencies in the market, as well as a willingness from the board to take on more risk. ERS also has a 7% actuarial assumption, an increasingly tall order for public pension funds investing in a low interest rate environment.

…..

About 60% of assets are managed in-house by about 60 investment team members overseeing various asset classes, including high-yield and infrastructure. Administrative and operational staff round out the 79-person team.

…..

Going forward, ERS will continue to look into credit, particularly in sectors that have been highly penalized, such as leisure and transportation. The pension fund is also looking at niche investments, such as data centers, medical facilities, and multi-family units.

I am not going to evaluate any of these potential investments.

I’m just going to say it can be very tricky, and I will link to a smattering of my posts on public pensions and alternative assets over the years:

- 2018: Alternative Assets and Pension Performance: A Dive into Data

- 2014: Public Pensions Watch: Don’t Go Chasing Waterfalls….or Alternative Asset Classes, pt 1 of many

- August 2014: Public Pensions Watch: Dallas Pension Learns About Concentration Risk

- September 2014: Public Pensions and Alternative Assets: Dallas Shows How It Can End

- 2017: Public Pension Assets: Our Funds were in Alternatives, and All We Got Were These Lousy High Fees

- 2015: Reddit-Public Pension Connection: Alternative Assets and Risk

- 2014: Public Pensions Watch: More Reactions to Calpers Pulling Out of Hedge Funds

- 2014: Public Pensions Watch: Alternative Assets, pt 8 of many — New Jersey followup

So that was today’s public pension ride — seeing old talking points trotted out again, then seeing an assertion that would have made me spit out my tea if I hadn’t already have finished it, and then an eye-popping amount on alternatives. (Really, Texas ERS is an extreme case….but it’s far from the most extreme.)

There are several things Texas ERS needs to work on, and someone looking into that alternative portfolio may be a good idea.