Are Public Pensions Actually in a Crisis? Or Is It Just a "Mathematical Issue"?

by meep

A couple weeks ago, Steve Malanga, who has written about public pensions for the Manhattan Institute (as well as on other topics and in different venues) had an op-ed in the WSJ titled The Pension Sink Is Gulping Billions in Tax Raises

A quick excerpt:

California Gov. Jerry Brown sold a $6 billion tax increase to voters in 2012 by promising that nearly half of the money would go to bolster public schools. Critics argued that much of the new revenue would wind up in California’s severely underfunded teacher pension system. They were right.

….

When California passed its 2012 tax increases, Gov. Brown and legislators promised voters the new rates would expire in 2018. But school pension costs will keep increasing through 2021 and then remain at that elevated level for another 25 years to pay off $74 billion in unfunded teacher liabilities. Public union leaders and sympathetic legislators are already trying to figure out how to convince voters to extend the 2012 tax increases and approve “who knows what else” in new levies, says taxpayer advocate Mr. Fox. It’s a reminder that in some places the long struggle to pay off massive government pension debt is just starting.

Of course, somebody had to respond.

That somebody was Keith Brainard of the National Association of State Retirement Administrators

Excerpt:

Pension liabilities don’t come due all at once, and pension costs are just 4% of all state and local spending. While Mr. Malanga correctly points out that as of 2013 public pension asset values were “only 1% above their peak in 2007,” left unsaid is that since 2007 public pensions distributed more than $1 trillion in benefits to more than eight million retirees and their survivors. Considering that the 2008-09 market decline reduced public pension asset values by one-fourth, and the funds have distributed benefits continuously since, the fact that asset values are above their precrash level is actually something to applaud.

Let me address this in pieces:

Pension liabilities don’t come due all at once,

No, but supposedly they will come due. Each year you have benefits to pay in addition to whatever new benefits are accrued by employees.

Pension plan contributions are supposed to cover the benefits accrued by work that year. If you don’t make those contributions in that year, you have to make up for it — and the assumed lost fund earnings — in subsequent years.

The specific cash flows don’t come all at once. Indeed, you were supposed to be paying for them all along.

and pension costs are just 4% of all state and local spending.

FOR NOW

Let me show you something:

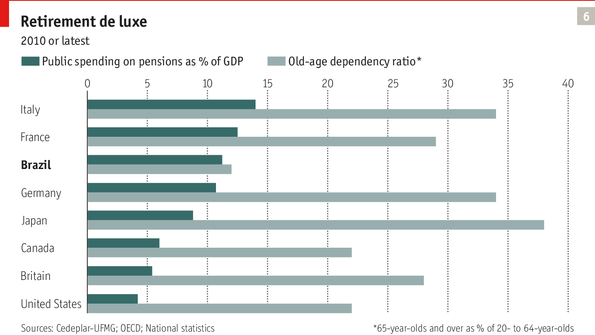

Oh, look, the U.S. at only 4%… of GDP. Not of total public spending (which sure as hell had be less than 100% GDP), which means the percentage being spent is higher than 4%. [That graph may be including Social Security in there, of course]

But take a look at those countries with fairly high percentage spending on pensions. That didn’t come all at once, by the way.

While Mr. Malanga correctly points out that as of 2013 public pension asset values were “only 1% above their peak in 2007,” left unsaid is that since 2007 public pensions distributed more than $1 trillion in benefits to more than eight million retirees and their survivors.

From funds that were already supposed to be there for them.

And additional contributions were supposed to be made in those 6 years to cover newly-accrued benefits.

So…..?

Considering that the 2008-09 market decline reduced public pension asset values by one-fourth, and the funds have distributed benefits continuously since, the fact that asset values are above their precrash level is actually something to applaud.

I have no idea whether to applaud it or not. It’s not only that cash has gone out the door, but additional liabilities were taken on. For most of the pension plans I’ve seen (except very small, closed ones), the total liability has increased over that period, and the assets have grown, but not enough to be fully-funded.

One appropriate measuring stick (by obviously not the only one) is how much assets are on hand to cover the promises already made – not future promises, not some of the earned benefits – but what should you have on hand now. They already measure this – you should be familiar with it from my 80 Percent Funding Hall of Shame.

For crying out loud, being 80% funded sucks if you’ve had multiple years of double-digit returns. Have you not been putting in money?

Increasing by 1% in bulk, when the liabilities have grown even more… no, I’m not going to applaud that.

Some of the commenters on the letter had similar things to say:

The first commenter:

John Segal 2 days ago

Oh yeah? Then why are the actuaries who calculate these things for a living saying there is a crisis?

It’s not all of them, of course, and I am not a pension actuary, much less one who works in public pensions. But yes, some actuaries are speaking out about the problem.

A few more comments:

William Bair 2 days ago

Two questions not addressed above would be (a) how much did governments have to contribute to pensions in the years since 2008 so that they could pay out as much as claimed and still have assets at the same level and (b) in the years from 2008 through 2014 how much did the overall obligations of government pension plans increase while EE’s worked and were earning increased benefits.While the assets today may be 1% above where they stood before the great recession what is the level of liabilities compared to that same time? The statements made in the article seem to be those one could make of social security—it must be financially sound because they haven’t missed a payment yet.

….

John Shniper 2 days ago

There is NO crises until the Money Runs Out! Greece all over again. This kind of mentality RUINS countries and NOT just for Old Men!

Yup, there’s that last bit.

I read this piece at Knowledge@Wharton titled Underfunded Pensions: Tackling an ‘Invisible’ Crisis, which starts to show why many people don’t take the problem seriously. The consequences either don’t sound bad or inevitable, for obvious reasons. The interest is too diffuse.

I was underwhelmed by the quotes in that piece, where participants in a one-day seminar titled Urban Fiscal Stability and Public Pensions: Sustainability Going Forward mainly make comments about taxes getting sucked up more to pay for pensions (Malanga’s point), and the closest to hinting at what really may come is hinted at in Professor Jonathan Rauh’s comment about “benefit parameter changes” — i.e., tinkering on the edges. Oooo scary.

The real end game? Detroit.

Here’s the problem: it’s a very slow-moving crisis, until it’s no longer slow.

The Detroit pensions were supposedly well-funded, and pensions of current retirees got hit anyway. That’s being allowed a formal bankruptcy process, of course.

When one isn’t allowed formal bankruptcy, you end up with a situation like Prichard, Alabama, where the pension fund actually goes to zero. And you try to pay for pensions for services rendered possibly 50+ years ago with current taxes. From people who weren’t around 50+ years ago, and they are fewer than the population from back then, so it’s not clear they can even sustain such payments even as new liabilities aren’t being taken on.

When you have a less-than-fully-funded pension, things can go really, really bad.

If you have the people running the pensions, some of which are okay, but many of which are extremely underfunded, trying to pawn it off as “just math”, look at what inevitably occurs.

Alas, I think you’re not going to get people’s attention by saying the taxpayers will get hit. Sure, they’ll get hit, for a little bit, but they’ll take only so much before they move away. Taxpayers have short-term issues to look at, and their concerns are diffuse.

You can tell the politicians it will be their legacy, but many treat it like a game of hot potato, assuming they’ll be long gone when the asset death spiral hits. Or maybe they’re delusional in thinking the taxpayers will sit there and take it.

The main target to get this crisis taken seriously are the public employees themselves. They need to know: if your plan is being deliberately underfunded, year-by-year, you have a non-zero probability of getting less (and maybe a lot less) in your pension than you were counting on. If public employees understand that they may not get what was promised, and the fix isn’t lawsuits against reform but actually demanding their pensions be funded.

No, don’t take the promise of higher pensions if they don’t fund it. It’s a lie.

What actually threatens the actuarial soundness of public pension plans is behavior like the following:

Not making full contributions.

Investing in insane assets so that you can try to reach target yield. Or even sane assets that have high volatility to try to get high return, forgetting that there are some low volatility liabilities that need to be met.

Boosting benefits when the fund is flush, and always ratcheting benefits upward.

…..

Because they thought that pensions could not fail in reality, that gave them incentives to do all sorts of things that actually made the pensions more likely to fail. Because, after all, the taxpayer could always be soaked to make up any losses from insane behavior.….

If the employee unions in Illinois knew that it was possible that they might actually only get 40% of what was promised, they might not have been so blasé about the undercontributions. They might have asked for more realistic investment targets.The explicit ability to renege on pensions (known by all parties) would make them less likely to fail, because employee unions would then have some incentive to make sure pension contributions are made, and they would be less likely to ask for benefits that may make their pension plan insolvent. If they knew that no, the taxpayer wouldn’t be there to bail them out of stupid investment decisions, they might not be so happy with all the opaque investments.

No, this is not a new theme for me, but it needs to be whacked as much as possible.

This will be taken care of only when the public unions and employees realize they can get whacked. And not just with “benefit parameter changes”.

Public employees: Demand full funding and prudent practices in your pensions.

Underfunding and too-risky investments will take their bite.

Don’t expect politicians, taxpayers, or lawyers to save you.

Steven Malanga Books:

The New New Left: How American Politics Works Today (2005)

The Immigration Solution: A Better Plan Than Today’s (2007, with Heather MacDonald and Victor Davis Hanson)

Shakedown: The Continuing Conspiracy Against the American Taxpayer (2010)

Related Posts

Nope, Not #MeToo...But Also Not Surprised at Sexual Harassment in Legislatures

Vladimir Bukovsky Makes the New York Times

Kentucky Asset Manager Warning: the ESG Brou-Ha-Ha Continues