Public Pensions Primer: Intergenerational Equity

by meep

You will often see the concept of intergenerational equity when it comes to public pensions (and Social Security, and other benefit plans…), but the concept is that it’s “fair” for a generation to pay in full for the benefits they promised to themselves/their employees.

The older people who promised the employees of 1980, say, that they’d get certain pension benefits should be the ones who paid for that cost.

Not coming back to those people’s grandchildren and great-grandchildren saying that they now owe the debt.

THANKS LINKERS!

Which reminds me, let me pay off my debt of thanks to my linkers:

- Pension Tsunami – for your public pension news fix

- Wirepoints – focus on Chicago and Illinois

- The Other McCain – with wombat-socho’s In The Mailbox feature, linking around the conservative blogosphere

Howdy to my students coming through my UConn faculty page, and to the people coming through twitter links!

SOME OTHER DEFINITIONS

But don’t take my word for the concept of intergenerational equity.

In the paper Financial Economics Principles Applied to Public Pension Plans, the authors (Ed Bartholomew, Jeremy Gold, David G. Pitts, and Larry Pollack) write:

Public Finance Principles

Intergenerational Equity

Intergenerational equity means that each generation of taxpayers pays contemporaneously for services received (Robinson, 1998). A police officer’s total compensation should be paid by those he or she protects. Thus, it should be part of the entity’s operating budget funded by current revenues. The cost of a newly built police station, however, appears on the capital budget and may be financed over time by the issuance of debt. Debt service becomes part of the annual operating budget, which allows generations of taxpayers to pay for a police station that serves them all.

They mention Robinson, 1998, which is Measuring Compliance with the Golden Rule by Marc Robinson, published in Fiscal Studies (1998), vol 19, no 4, pp 447 – 462.

From the introduction of the paper:

Intergenerational equity is widely regarded as a key fiscal policy criterion. A key traditional conception of intergenerational equity is embodied in the so-called ‘golden rule’ of public finance. The golden rule asserts that taxpayers in each time period should as a group contribute to public expenditures from which they derive benefits in accordance with their share of the benefits generated by those expenditures. In doing so, they may be regarded as ‘paying their way’, without either subsidising, or being subsidised by, taxpayers in other time periods.

It seems that Robinson works in Australia, thus the odd spelling.

WHY FAIRNESS?

Most explanations of intergenerational equity I see cast it similar to Robinson: it’s only fair (aka equitable) for generations to pay for what they bought, rather than push it to later taxpayers.

While “fairness” is always a popular concept in politics, it’s pretty weak with regards to political action. Great to get people to march in protests, but not so great in developing substantive policy. Or getting the results you desire.

And, at any rate, why you should care about intergenerational equity is not really fairness. It’s about what stakeholders actually being secure in being able to get what they want.

Key stakeholders in this situation are: current taxpayers, current employees, retirees, and bondholders.

Current taxpayers generally expect something in exchange for taxes…. namely, current services.

Current employees would like to get paid, including benefits they can rely on, and in exchange, provide current services.

Retirees would like to get the pensions they were promised.

Bondholders want to get paid what they were promised.

Oh, and I forgot about the decision-makers, aka politicians. They would like to stay in their cushy positions or move up to a higher office.

Thing is, prior taxpayers often did not pay full freight for the benefits promised to current retirees, who provided services to the prior taxpayers. The prior taxpayers did not pay full freight for a variety of reasons:

- valuation approaches and assumptions that minimize the apparent cost of the benefits promised

- they issued bonds instead of providing tax money to fund the benefits (arbitrage!)

- they assumed pensions would be made whole by later generations of taxpayers

- 80% funded is healthy!

The financial economics paper addresses the first item, but I don’t want to get into valuation theory.

Because even with the valuation assumptions making pensions look cheaper, many plans weren’t making what was calculated to be full payments.

WHAT RESULTS

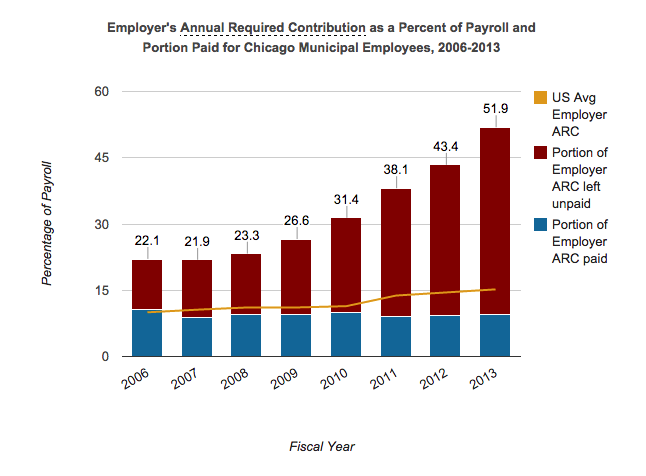

Here’s one of my favorite examples of underpaying, the Chicago Municipal Workers plan:

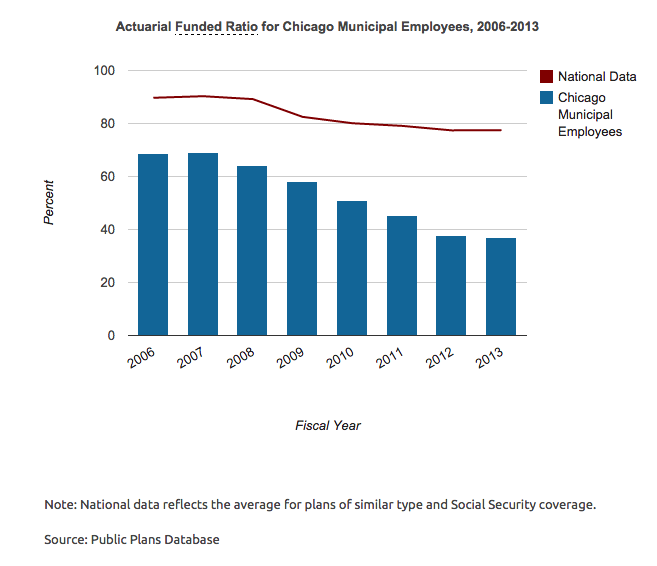

This is the result:

Now, we’ve seen that Chicago is trying to boost taxes to make up for that huge hole in funding, but they are finding that current taxpayers aren’t too pleased with the situation. Those are the ones already passed. The politicians are looking for more taxes. Taxes, taxes everywhere!

Thing is, Chicago has a population problem.

This points up one of the big reasons for intergenerational equity:

Later generations may not show up to pay.

ILLUSTRATION: CHICAGO

Let’s consider the theoretical case of someone who retired in 2000 after 30 years of service in Chicago. The pension was short-changed in the years before retirement, but eh, there have been some pension obligation bonds issued. And besides, the pensions have got to be paid!

Thing is, maybe this retiree has moved to Florida. So they no longer (legally) vote in Illinois. They don’t pay taxes there.

Their children and grandchildren (if they have anything) have also moved elsewhere. New people have moved to Chicago, of course, but what do they care about the service provided in 1980? The retirees can’t strike, after all. Maybe they can look pitiful at the cameras, but that didn’t do so much for the retirees of Detroit or Greece.

Crying “BUT YOU PROMISED!” is not going to help when the people you’re yelling at weren’t the ones who did the promising.

Yes, Illinois and Chicago (and many other places) are trying to get money out of current retirees (and bond buyers), but, well…

Chicago’s Pension Funds Need More Support

In the graph, the blue bars show Chicago’s annual contributions to the four pension plans combined, and the red line shows their combined funded ratio. Where possible, the graph uses recently released official projections. In all other respects, the graph reflects our own projections based on official actuarial assumptions and statutory funding requirements.

For the 10 years through 2014, Chicago contributed less than $470 million per year to the plans. These contributions were insufficient even to maintain the funded ratio, which went from a poor 61% at the end of 2005 to a dangerously low 31% at the end of 2015.

By 2019, the city’s annual pension contribution is expected to be $1.3 billion – an increase of $827 million, or 176%, above the 2014 contribution. Over the three years thereafter, the annual contributions are expected to jump another $741 million, to $2.0 billion in 2022. All of Chicago’s recent and proposed tax increases combined will be insufficient to fund these increases. We estimate the shortfall will be $647 million in 2022 alone.

After 2022, we project contributions will increase every year through 2055. Over that period, the annual contribution will increase by another $1.9 billion, to $4.0 billion in 2055 – 8½ times what the city was paying in 2014.

Do these steep increases provide steady progress toward proper funding? No. In fact, the plans’ funded ratio will actually drop over the next several years – from 31% in 2015 to 26% in 2021 – and their unfunded liabilities will increase until 2033. It will take until 2030 for the funded ratio to return to 31%; until 2050 for the funded ratio to be restored to where it was in 2005 (61%); and until 2057 for the ratio to reach 90%.

The graph’s projections assume that the official actuarial assumptions prove correct, and Chicago will make the annual contributions mandated by law. If history is any guide, these assumptions will prove overly optimistic, and much more money will be needed.

For example, the city’s pensions continue to assume that their investments will earn 7.5% per annum. This assumption is dubious. Many public pension plans, including Illinois’s largest, have reduced their assumed return to 7.0% or below. This change would significantly worsen the numbers discussed above.

To be clear, we are not attacking pensions. To the contrary, we believe employees should not be put in the position of serving the city for many years yet left guessing whether the city will be able to pay their pensions. The only way to avoid this is for the city to contribute actuarially sound amounts to the plans every single year. By ignoring this precept, the prior administration dumped a big mess on Mayor Emanuel’s lap.

Good luck with that.

Thing is, how long will Rahm last as mayor if the next person comes along saying “Hey, let’s tax the wealthy people! And grab money from whereever!” … without considering whether they’ll actually be able to get that money.

There is a limit to the taxes they can hike in many respects. Remember, the politicians want to keep their cushy positions (until, all of a sudden, they don’t look cushy any more… hey, Rahm, why do you think Daley left?)

Here’s a New Jersey example of intergenerational equity being broken, courtesy John Bury:

New Jersey Policy Perspective (NJPP) released a report yesterday citing nine bad decisions made over the last quarter century by Republican governors and the courts that brought New Jersey to this bankrupt state which they teased with a youtube:

…..[go to post for video]…..

Twenty-five years of blatant generational theft under various guises have made the possibility of any type of generational equity going forward impossible (except if benefits were to be cut to the level at which they were funded which would mean about an 80% immediate across-the-board cut).

Perhaps instead of ‘preserve’ the FE authors had inserted ‘take a stab at’ it would have made some sense since you can’t preserve something that never existed.

Neither Bury nor I am talking about theory here.

The reality is that intergenerational equity has been broken in many places. So saying it’s a principle of pension financing, when it’s been blatantly violated for so long for key sponsors… this paper isn’t going to help fix the political problem.

INEQUITY MEANS INSECURITY

The problem with intergenerational inequity is not about unfairness. It’s about danger to all the stakeholders. When pensions are grossly underfunded, on purpose, as we’ve seen in Chicago and New Jersey, you get the following results.

Current taxpayers see more and more of their taxes not paying for current services, but for services they didn’t receive at all. Current services get reduced so that pensions can be paid.

Current employees find their pay stagnating, and then they see their pension benefits are less rich than prior generations. The contributions going into their pension fund are going to current retirees, and they don’t think the pensions will be around for them.

Retirees think they will be the last to get whacked, but that’s not always the case. They will continue to get their benefits… until all of a suddent they find their fund is bankrupt. Some places allow less catastrophic adjustments to current retirees, but many wait until the money actually runs out. When you’re in an asset death spiral, this will eventually happen.

Bondholders, who are often retirees themselves, may see themselves being defaulted on.

Politicians realize they’re in a precarious situation, so try to do tax boosts as sneakily as they can. They still get booted from office.

Pretending that the pensions (or bonds) aren’t in danger is foolish. It just makes catastrophe happen.

Intergenerational equity is important not because it’s only fair, but because breaking it means you make the pensions insecure, and there are lots of bad results.

UNDERCONTRIBUTING MEANS UNDERPAYING RIGHT NOW

Current workers, you want to make sure your current benefits are paid for, or you may find you end up with less than promised.

Think you would be happy if your employer paid you half what you expected, and gave you an IOU for the other half?

No, you would be suing.

Workers, every time your benefits are underfunded, you are getting underpaid. You’re not being cheated when the pension benefits are cut 30 years in the future when you’re retired. You’re cheated the year you provided the services, and the politicians underpaid the pension fund.

Intergenerational equity is about your total compensation actually getting paid, workers.

I’ll address the theoretical aspect another time (just how much are the benefits worth?), but the practical aspect is that whatever the valuation basis, if there is a deliberate policy of undercontribution, current employees are being cheated.

Future taxpayers and bondholders may also be cheated…. but they also may not exist.

Related Posts

New Jersey's Pension Non-Solution: Giving the Fund Management to the Unions

LA Teacher Strike Ends: Promises Made With Money Not in Hand

MoneyPalooza Monstrosity! The Positioning for Asking for State Government Bailouts