A New Category for the Public Pension Hall of Shame: Never Fully-Funders

by meep

I thought once might be a coincidence. But, unlike Auric Goldfinger, I will jump to conclusions of adverse intent with a sample of two: I have a new category for the 80% Hall of Shame, and it’s those who say public pensions never have to be fully-funded.

Hell, that they shouldn’t be fully-funded.

(My new category is called the “Never Fully-Funded List of Evil”… yeah, it’s not catchy, but it’s less obscure than Malebolgia 8)

Today’s entry is a triple with their op-ed Why full funding of pensions is a waste of money

WHO IS TO BLAME

Before I get to the text of the piece, let us check who these three people writing the piece are:

John J. McTighe is president of Retired Employees of San Diego County.

Jim Baross is president, City of San Diego Retired Employees’ Association.

David A. Hall is president, City of San Diego Retired Fire and Police Association.

OH LOOK, PEOPLE WHO ARE ABOUT TO SAY THEY’RE FINE RECEIVING LESS THAN THEY WERE PROMISED.

I think if or when San Diego has to cut payments to retirees, these three people should be targeted first. After all, they said it was a waste to actually pay for retirement benefits.

THE ARGUMENT, SUCH AS IT IS

First, they’re just repeating the argument from the first guy I just put on my Evil List of Evil:

In fact, full funding of public pension plans isn’t necessary or even prudent for their healthy operation, according to a recent analysis by Tom Sgouros of the Haas Institute in Berkeley.

Ok, they’re not going to do anything new. Here was my original post on Sgouros’s paper:

Why It’s a Good Idea to Fully Fund Public Pensions

I can’t believe I have to write this.

And yet, here we are.

I am still appalled about that initial action of Original Sin of Public Pension Funding: the argument that it’s not a good idea to target full funding of public pensions, in a paper titled Funding Public Pensions: Is full pension funding a misguided goal?

My own re-titling of the paper it: “Funding Public Pensions: Is actually paying the promised benefits a misguided goal?”

So now come three people representing public employees and retirees deciding to grab onto Sgouros’s argument. Let’s see the argument as they present it.

In the private sector, pension systems need to be 100 percent funded to protect the pensions of workers in case of bankruptcy. In the public sector, however, while governments may encounter periodic budget ups and downs due to economic cycles and fluctuating revenues, they are not going away.

GOVERNMENT NEVER GOES AWAY?

Catch-Up Week: Puerto Rico on the Brink (again)

California Consequences: Turns Out, Pension Benefits Can Be Cut

Detroit Bankruptcy: It’s Over, But It’s Not

That’s just a sampling of posts and stories of public finance failure. In the case of Detroit, the pensions supposedly were fully-funded (they weren’t), and pretending that the 90%-ish “fully funded” figures would have been better replaced by 70% funded figures… yeah, the Detroit pensioners already unhappy with pension cuts would have been happier with deeper cuts. Just think that one through.

WHY GIVE PUBLIC EMPLOYEES AND RETIREES ANY SECURITY, RIGHT?

Back to their op-ed:

Full funding of a public pension plan amounts to covering the total future benefits of all current workers. The Hass Institute analysis describes this as a waste of money because it equates to insuring against a city or county’s disappearance.

It’s Haas Institute, btw.

So you’re happy going bare the risk of government bankruptcy for public employees and retirees? This is not purely theoretical, as they very well should know. They’re in CALIFORNIA, where there has been both Stockton and San Bernardino bankruptcies lately, the closed Calpers plans with retiree benefit cuts of over 50%, and they should sure as hell know what happened in Detroit.

But hey, these guys are official representatives of San Diego public employees and retirees. I will note they are fine taking that risk.

When San Diego goes down, the rallying cry will be “But government doesn’t go out of business!”

THE BAD ANALOGIES

Oh dear lord, this is stupid.

Imagine you sign a lease to rent an apartment for 12 months at $1,000 a month. Your ultimate obligation is $12,000, but should the landlord refuse to rent to you if you can’t show you have $12,000 available at the outset of the lease (100 percent funding)? No, the landlord simply wants assurance you can pay your rent each month.

You’re accruing the value of the ability-to-live-in-the-apartment month by month. No, you don’t have to pre-fund operational expenses being paid as they’re accrued. That said, many landlords do require at least an indication of liquidity by putting down a month or two of deposit.

If you’re a homeowner, you probably have a 30-year mortgage. Your mortgage allows you to own your home without fully funding the purchase. If, for example, you have a $300,000 home with a $150,000 mortgage, it might be said that your homeownership is at a 50 percent funded ratio. That’s not reckless; it’s prudent use of debt.

Ah, the good old mortgage argument.

A house is not merely an operational cost, but a capital cost. (Yes, there’s an imputed-value-month-by-month-of-being-able-to-live-there, akin to rent…no, I’m not using the technical accounting term.)

At any point, you could sell the house. As it’s an actual asset.

Retirement benefits, i.e. paying for current services with cash later, are an operational cost. You can’t sell past services to some investor. They’re gone. They’re not an asset.

A bridge employees built (have you heard about this bridge over the East River? Have I got a deal for you!) – sure, you can sell that. But that’s not a pension obligation.

Each of these examples involves an ultimate obligation to pay off all the debt by a specific date. Public pensions are different in that the obligation is open ended, but so are the income sources.

No, the obligation is not open-ended. First, a given employee will stop accruing pension benefits at some point, and the pension benefits will stop being paid for a retiree (or beneficiaries) at some point.

The mistake is trying to make it a mass phenomenon. The pension liabilities are accrued by individuals, not some amorphous, ever-renewing mass of worker-blobs. You don’t have unicellular public employees fissioning all over the place, truly creating an open-ended obligation.

The proper analogy isn’t a mortgage. Or rent.

It’s your credit card balance.

You think you can sell your own credit card balance to somebody? Nope, there is no linked asset to that debt. It’s just the debt from overliving your means.

(Yes, it’s an asset to the credit card company. Just as, the pensioners and employees hope, that the promised pensions are assets to them.)

PENSIONS CAN NEVER DIE…UNTIL THEY DO

Continuing from their op-ed:

Let’s consider a pension fund that has 70 percent of what it needs to pay all retirees decades in the future. During any given year, the pension fund must pay promised benefits to current retirees. Provided that annual contributions from the employer and current employees, combined with investment returns, are equal to benefit costs, the fund operates at break-even.

If at the end of the year the fund is at 70 percent, it’s a wash. The fund can go on indefinitely under these conditions. According to the Haas report, America’s public pension systems were, on average, 74 percent funded as of 2014.

THAT’S NOT GOOD YOU IDIOTS.

At this point, we’ve had the Detroit city pensions whacked. Just because MEABF hasn’t run out of cash yet doesn’t mean it will never fail.

There are two strong reasons not to move to 100 percent funding.

First, doing so would require significant, unnecessary expense to employees, employers and taxpayers.

Since public pensions can exist indefinitely at 70 percent or 80 percent funding, why not use those funds for more immediate needs?

Yes, they can exist indefinitely at 70-80% funding, but only under specific circumstances:

- the payroll and, more importantly, the tax base keeps growing steadily

- benefit levels and retirement ages get adjusted to keep pension value growth in check.

THE “THEY CAN’T BE TRUSTED TO BE RESPONSIBLE” ARGUMENT

I love this particular argument from the op-ed:

There’s a larger concern, though.

Historically, when pensions in California approached 100 percent funding due to unusually high investment returns, policymakers reduced or skipped annual contributions, under the flawed assumption that high market returns were the new normal. They also increased benefits without providing adequate funding, again expecting investment returns would cover the cost. When investment returns returned to normal, these decisions had long-term negative consequences.

Okay, let me break this down for you.

I would like to see that history. Did it happen more than once? I know the one time it happened in California, all over the state.

Not every state was as idiotic as California, granting pension boosts retroactively.

But here’s the question: if you just move the target from 100% funding to 80% funding, what’s to stop them from doing this maneuver when the pensions are funded at 85%?

If they’re not trustworthy when the target was 100%, they’ll certainly not be trustworthy when the financial bar is lowered.

JUST HOW STABLE IS IT, REALLY?

Here’s their close:

So when you hear concerns about public pensions being underfunded, understand that ensuring 100 percent funding isn’t critical to the healthy functioning of a public pension system, and it can be very expensive.

Both the city and county of San Diego pensions systems are quite stable at a 70-80 percent funding ratio.

Sure. They’re stable right up until they’re not.

But before I address that, let me check on these people writing the op-ed. Transparent California has some nice records.

John McTighe’s 2016 pension was $126K – he retired in 2007. I don’t know how many years of service he had.

Jim Baross’s was $110K, and he also got a DROP payout of $19K when he retired. I don’t know what year he retired, but he had just over 37 years of service.

David A. Hall has a pension of $104K for 32 years of service. Again, I don’t know when he retired.

I’m not quoting these to get snippy about the $100K club – after all, I make more money than that and I don’t think that these are necessarily excessive amounts.

If they were pre-paid for.

The reason I quote these is because I want to ask them: would you be okay getting only 70% of that?

Would you be wiling to take even larger cuts than 30%, like the Calpers pension orphans? How about 60% cuts? Would that be fine with you?

Because let’s see how “stable” San Diego’s pensions really are.

SAN DIEGO STATS

The Public Plans Database has only two San Diego pension plans in it: the San Diego County ERS and the City ERS. Evidently the police & fire pensions are rolled into the city plan.

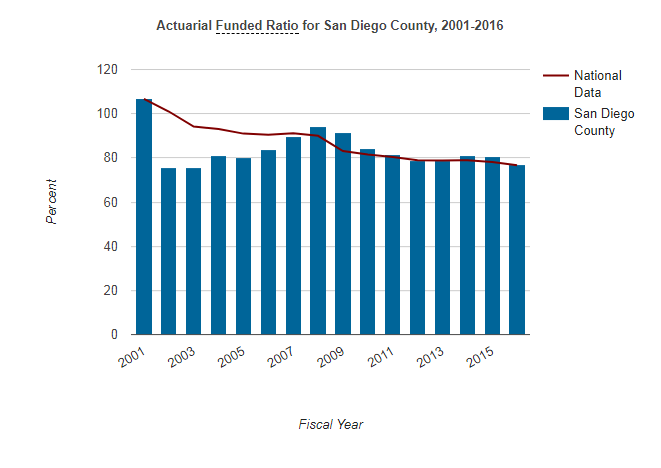

San Diego County fundedness trend:

The county plan dropped from 94.4% in 2008 down to 78.7% in 2012 (I assume they use asset smoothing to prevent the large market drop of 2008 to affect the fundedness).

San Diego City ERS fundedness trend:

The city plan dropped from 78.1% fundedness in 2008 to 66.5% fundedness in 2009.

Mind you, San Diego, both city and county, are “full funders” in terms of paying 100% of ARC.

And yet, their funded ratios haven’t improved at all through several years of a bull market. They’re both hovering between 70 and 80% fundedness and have for several years.

What happens when there’s another market crash?

You willing to take the hit, guys? Or do you think the taxpayer will always be there for you?

What if they skedaddle, as per Detroit?

Are you willing to take a 60% cut?

LESS THAN FULL FUNDING MEANS LESS THAN FULL PENSION BENEFITS

In the short term, sure, governments can keep treading water with their pensions and bonds.

It looks like property taxes have been going strong of late:

Property tax revenues have been on the rise: https://t.co/pMNo5CugJu pic.twitter.com/iMWVLvHYcE

— SanDiego UT Graphics (@sdutgraphics) September 27, 2016

That’s a 5.5% compound annual growth rate, which isn’t too shabby. But I’ll note that this data go back only 5 years. Kind of curious what the longer-term trend is.

Tax bills show increased growth, but slower rate:

Last week San Diego’s tax collector sent out nearly 1 million bills in an attempt to collect nearly $5.7 billion in property tax revenue. That’s a record figure, but the rate of growth in the county has slowed.

Dan McAllister, the county’s treasurer-tax collector, put 989,089 annual secured property tax bills in the mail, and if everyone pays their share, the county will receive $5,662,765,208 in revenue, a 5.42 percent increase compared to last year.

…..

The rate of growth for both the number of bills and the projected tax revenue is the lowest in three years, data show. Last year the number of bills grew 0.23 percent, by 0.28 percent the year prior, and 0.12 percent in fiscal 2013. The revenue increased by 5.88 percent last year, by 5.45 the year prior, and 5.56 in fiscal 2013.The housing market is one of the hottest policy issues in county. The cost of home ownership is out of reach for many residents, but changing land use regulations to allow for the construction of new homes is often opposed by people who are concerned about increased traffic, crowding in schools and environmental issues posed by new development.

Yeah, sounds like that 5.5% annual growth rate isn’t going to persist.

But back to the point: if, after a long bull run, the pensions can’t even break through 80% fundedness, that’s not a sign of “stability” but a sign of weakness. If a 20% market drop occurs – what then? Start telling retirees that 50% fundedness is just fine?

In the long run, a 70-80% target gets beaten down to 60%, and then when it’s pay-as-you-go, that can run for a bit.

But not forever.

POSTS ON FULLY FUNDING PUBLIC PENSIONS

Why It’s a Good Idea to Fully Fund Public Pensions

Public Pensions Primer: Why Do We Pre-fund Pensions?

Public Pension Watch: The Fragility of “Can’t Fail” Thinking

Watching the Money Run Out: A Simulation with a Chicago Pension

80% Public Pension Funding Hall of Shame (plus Never Fully-Funded List of Evil, and Heroes List)

Related Posts

Happy Pension News: Wisconsin State Pensions...a Beginning

Public Pension Assets: Our Funds were in Alternatives, and All We Got Were These Lousy High Fees

Show Me (the Money) State: Missouri Tries a Pension Buyout