South Carolina Pensions: Liability Trends

by meep

So here we go. I have pretty much beat the asset-side problems into the ground, but that’s not the only problem with SC pensions.

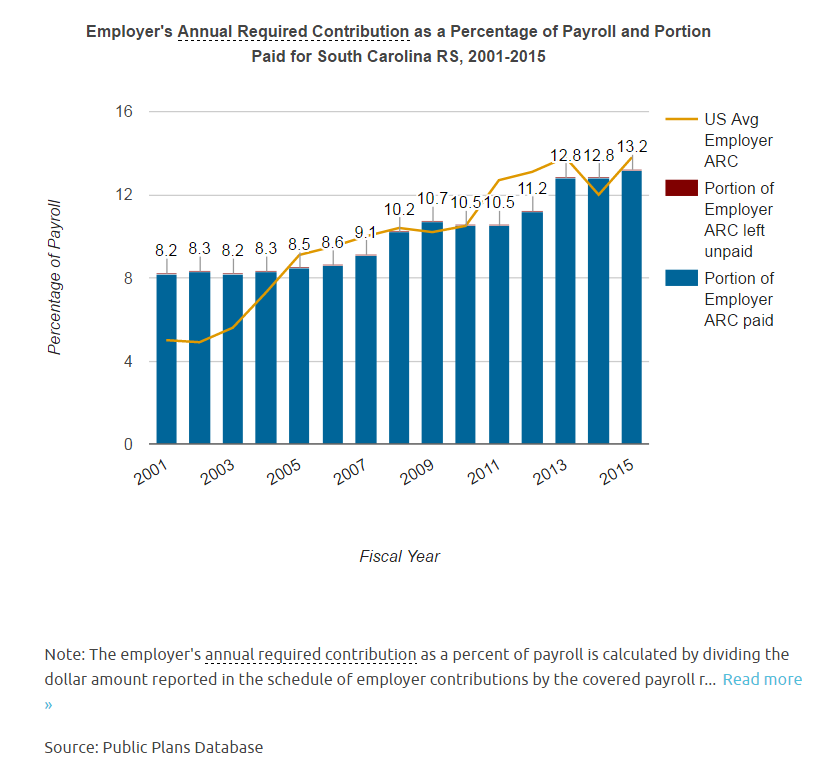

I mentioned this in earlier posts — SC has supposedly been making full contributions:

And yet the funded ratio has been doing this:

That the funded ratio does nothing but go down, even when they’re making “full” contributions, is very awry.

Alas, it’s not specific to SC.

I mentioned this kind of behavior when it was assuming a growing payroll that didn’t grow. More on questionable assumptions here.

For the longest time, I’ve focused on what discount rate/assumed rate of return assumption was being used. It’s a very simple lever to look at effect, and it does have a profound effect. But there are lots of other assumptions as well.

And methods.

CURTIS LOFTIS POINTS OUT A PROBLEM

Yes, state Treasurer Curtis Loftis again. I had noticed the asset issue, just as Treasurer Loftis had, years ago. But Loftis pointed out something I didn’t know:

S.C. treasurer, armed with attorney general opinion, blasts pension fund management

COLUMBIA — South Carolina’s struggling pension funds, which serve roughly one of every nine state residents, are in even worse shape than they appear, according to the state treasurer.

Treasurer Curtis Loftis points to a recent opinion from the Attorney General’s Office, which he requested, that says a court would likely find the methods used to calculate the pension plan unconstitutional. Loftis said those methods mask the impact of years of underfunding.

If the pension fund liabilities were calculated the way Loftis and the Attorney General’s Office say is the correct way, the known $24 billion shortfall in long-term pension funding would be revealed to be larger, requiring more money from governments and government employees.

“It’s probably the most jarring AG opinion I’ve read, as a constitutional officer of the state,” Loftis said.

The General Assembly and the SC Public Employee Benefit Authority, Loftis alleges, have obscured the depth of the shortfall, allowing the Legislature to delay inevitable but expensive solutions.

…..

The details of the financial calculations and assumptions Loftis is criticizing can seem complex, but essentially, the state uses a 30-year time frame to calculate the health of its pension funds and the contribution rates required. Loftis said that currently, that 30-year period is extended every year, in what’s known as an “open” amortization schedule, and assumptions about future increases in contribution rates are included to calculate funding gaps.

Open amortization?!

Both the use of open amortization, and counting future rate increases that haven’t been voted upon or funded, are fraught with legal problems, according to the attorney general’s opinion. Instead, the state should used a “closed” 30-year amortization schedule based upon current contribution rates.

Wait… what?

As a result of what Treasurer Loftis has pointed out, the State Attorney General wrote a letter.

The two key points in the letter:

I. The calculation of the amortization schedule of the unfunded liabilities of the South Carolina Retirement System should be based on a closed amortization schedule.

II. The amortization schedule should not be based upon contribution rates which have not been adopted by the PEBA Board, approved by the SFAA.

Just as in the article: open amortization is a problem, also assuming higher contribution rates in the future.

OPEN AMORTIZATION: AN ILLUSTRATION

This explanation is in the linked article from before, but I will do it myself, and again, in terms of a home mortgage, which most people can understand.

So let’s assume you buy a home, and you get a 30-year mortgage for it. No big deal. The level payments are calculated so that the balance is paid off over time.

Let’s assume after one year, you basically refinance to another 30-year mortgage for the remainder of the balance.

And the year after that, you do the same thing.

Etc.

Will that mortgage ever get paid off?

I leave this as an exercise for the reader, because that’s not exactly what’s going on here… because not only is the mortgage getting “refinanced” every year, but there’s debt added each year.

Imagine running up your credit card bills every year to cover your living expenses, and then rolling it into your mortgage each time you “refinance” to another 30 year period.

Oh, and it’s not a level payment mortgage, but you assume the payments will increase in the future, so you end up with negative amortization. You’re not making large enough payments even to cover the interest payments, so the balance keeps increasing… and you keep adding to the balance with additional expenditures.

At some point, your payments are covering more in the way of past underpayments than you are from your original amount you’re borrowing.

Negative amortizing mortgages were a big part of the subprime mortgage market imploding from 2007 to 2008.

And now we’re seeing the same thing in pensions.

THEODORE KONSHAK POINTS OUT PROBLEMS

Konshak has done a lot of the work already – so I will link to his original documents and quote them. I thank Konshak for pointing out to me the importance of issues beyond the asset return assumption.

South Carolina Pensions: Actuarial Basics

The funded ratio of the South Carolina Retirement System as of July 1, 2016 is 59.5%. In simpler language, the funded ratio is the value of the fund’s assets divided by its liabilities (the amount of money it should have). If the actuary determined a pension plan was 100% funded, in the absence of trickery, this would mean the pension plan has all the money it needs to meet its current obligations. To the casual reader, the difference between the actuarial value of assets and market value of assets is nominal and should be of no concern.

…..

The Normal Cost is amount necessary to fund the pension benefits to be earned in the upcoming year. All of the employee contributions are used to fund that Normal Cost. Of the 11.99% to be contributed by South Carolina, 1.18% goes towards the Normal Cost and the remainder is used to amortize the unfunded liabilities. The large disparity in the Present Value of Future Normal Contributions is directly attributable to the disparity between that 1.18% and 9.09% of line 3(b).

….almost all of the payment is to deal with the unfunded liability?!

WHAT?

Negative Amortization

The huge problem facing the South Carolina Retirement System is the negative amortization of that $18.566 billion. In more technical terms, on page 26 of the July 1, 2016 actuarial valuation report, negative amortization is described as the level percentage of payroll amortization method.

In the negative amortization of a home mortgage, the mortgage payment is insufficient to pay the interest on the loan. The loan balance grows by the amount of the shortfall. In the negative amortization of a pension plan’s unfunded liabilities, the amortization payment is less than the interest payable on the unfunded liabilities. The unfunded liabilities are expected to grow by the amount of the shortfall. In a good year these unfunded liabilities may decrease but in an average year they are expected to grow by the shortfall. Continuing to use this negative amortization year after year, the unfunded liabilities can be expected to grow larger and larger each year.

Similar to a home mortgage, if a state consistently pays less than the interest on the unfunded liabilities, the unfunded liabilities or loan balance can grow to staggering amounts. As the unfunded liabilities continue to grow, so does the payment to amortize the unfunded liabilities.

The contribution will grow so large that employee contributions may eventually have to be siphoned off in order to pay those unfunded liabilities.

I previously discussed negative amortization in an article on scribd called

Public Employee Pension Systems: A Tale of Two Carolinas

.

Magnitude of Negative AmortizationTo cite an example, if the negative amortization was eliminated from the Chicago Teachers’ Pension Fund, their contribution under the requirements of the Governmental Standards Accounting Board (GASB) would increase from $755 million to $1.076 billion. That is more than a 40% increase.

Negative amortization is just awful, and I’m finding it more and more often when I start digging into the liability side of public pensions.

As Konshak has written in multiple posts, the people who are key in pointing out negative amortization are actuaries.

And what have they been saying? Any warnings?

Public Employee Pension Systems: A Tale of Two Carolinas was mentioned in that post:

Comparison of Two Carolinas According to the December 31, 2015 actuarial valuation report, the Teachers’ and State Employees Retirement System of North Carolina is 92.5% funded. According to its July 1, 2016 actuarial valuation report, the South Carolina Retirement System (SCRS) is 59.5% funded.

Both the Teachers’ and State Employees Retirement System of North Carolina and the South Carolina Retirement System would have gone through the Great Recession. There has to be another explanation for the difference in their funded status. Explanations frequently presented by journalists are simply too small to financially explain the disparity. It has to be something really large. So, why is one of the Carolinas so much better funded than the other?

…..

UAALThe amortization of the unfunded actuarial accrued liability (UAAL) of the Teachers’ and State Employees Retirement System of North Carolina is described by its actuaries on pages 41 and 42 of its December 31, 2015 actuarial valuation report:

“… North Carolina pays off a much larger amount of UAAL compared to other states. While many states struggle to pay a 30-year level percentage of pay UAAL contribution, which doesn’t even reduce the amount of UAAL, North Carolina pays down the UAAL with level dollar payments over 12 years. This aggressive payment of UAAL results in North Carolina being home to many of the best funded Public Retirement Systems in the United States”

I have connections to both of the Carolinas, so I’m happy for one part of my family that the NC pensions look well-run. I’m very unhappy for another large part of my family (some state employees) because SC is in a bad way.

I’m happy my grandmother wasn’t affected by this.

Konshak points out that the SC pension problem preceded the big market drop in 2008:

If you tell me the financial problems of the SCRS are due to the financial crash of the stock market in 2008, I will be calling you a liar. In the years from 2005 to 2007, the SCRS is already in financial distress. Look at the progression of the funded ratios in the third column from the right. The actuaries in the period from 2005 to 2007 sitting in that automobile stalled on the railroad tracks should have been yelling: “Freight train a comin’ down the tracks!”.

….

The train a comin’ down the tracks is not switching engine with only a few railroad cars attached. It is a long and heavy freight train of Baby Boomer retirements that will be a comin’ down the tracks under a full head of steam.The actuaries sitting in that stalled car are professionals and are the only ones with the education and training to see that fully loaded freight train heading their way. The driver of that automobile lacks that education and training and doesn’t see the freight train barrelling down upon them.

Rather than yelling a warning, the actuaries continue to sit in the car and collect their fees. At the last possible moment prior to impact, the actuaries will jump out of the automobile and save themselves without any regard for the safety of the driver.

Just as Jeremy Gold asked: Where are the Screaming Actuaries?

Note: I’m an outsider to this field. I have never done pension actuarial work — I’ve done actuarial work for annuities, life insurance, and reinsurance. I’m looking at publicly available info.

And I’m appalled.

I have talked with people who are insiders — is there a duty to warn?

Apparently not.

These two items from Konshak are also related:

Public Sector Pension Plans Failing to Implement a Meaningful Funding Policy and Its Aftermath

The South Carolina Future Payroll Growth Assumption

SOUTH CAROLINA IS NOT ALONE

Here’s the deal, though. I’m finding this crap all over the place once I start digging. NC seems unusual with its relatively short amortization period and using level dollar, as opposed to level percent of payroll. Yay for NC:

But let’s get back to the regular practice. Here is a graph I did, where I filtered on plans supposedly making 100% contributions.

I labeled a few of the points, but every point below that black line indicates an erosion in funded ratio. If it’s above the line, the funded ratio improved between 2001 and 2015.

I need to dig into the “bad” pensions more. Note the Kentucky County results. I have a post in draft on that particular plan.

MEEP STILL HAS A QUESTION

So actuaries, who have watched this happen:

There are certain valuation and funding practices, not to mention certain combinations of assumptions, that make for very bad results when reality deviates from these assumptions.

And yet, some are still being used.

But here are the public pension actuaries:

¯\_(ツ)_/¯

In many cases, though, having talked to a variety of public pension actuaries, many are true believers. It’s silly for me to complain about “absurd assumption sets” when they don’t see them as absurd at all.

But what would it take? Would it take plans that always pay 100% ARC and yet have decreasing funded ratios? Would that do it?

Seemingly no.

Well.

I am very unhappy with this crap.

I could not do anything this bad in valuing annuities. At least, I couldn’t get away with this and still be employed, much less not be prosecuted by the SEC.

OTHER COMMENTS

So you know how I, Treasurer Loftis, and Theodore Konshak feel about this stuff. Let’s get some more opinions!

SC Pension Debacle: Another Voice

DON’T TRUST LAWMAKERS TO PROPERLY FIX THEIR OWN COSTLY INCOMPETENCE

Following the lead of S.C. treasurer Curtis Loftis – who has made fixing the Palmetto State’s busted pension fund his mission since 2011 – this website has expended plenty of bandwidth calling on state leaders to prevent this inexcusable disaster.

Risky, corrupt methods, exorbitant fees and unconscionable bureaucratic neglect and excess have created a $25 billion debt.

“The pension debt is the massive pothole you can’t see,” Loftis wrote this week. “It is the debt that is larger than our state budget. It is the one issue that will cause taxes to rise and money for education, law enforcement, and essential services to dry up.”

For years Loftis issued warnings … unfortunately, none were heeded. As a result things got worse. And now “worse” has become downright catastrophic for South Carolina taxpayers.

….

Despite the worsening outlines of the debacle, Republican lawmakers in Columbia, S.C. and outgoing governor Nikki Haley have done their best to avoid the mess they’ve made. That approach is going to get very costly, very fast. A $100 million bill for this incompetence just came due last month, and that tab could increase by five- or six-fold within the next few years.Aside from drawing and quartering the morons responsible for this madness, what should be done? Stay tuned … we’ve got some ideas we’ll be sharing in the weeks to come as this issue moves front-and-center before the S.C. General Assembly (whether they like it or not).

That above piece linked to this item: Better homes and pensions by Phillip Cease

MY LAST NERVE: Legislators burned our house

Earlier this week, a state House and Senate panel offered its solutions to fix South Carolina’s pension system, which is anywhere from $20 billion to $74 billion in debt, depending on who you ask. What isn’t being discussed much now is how the pension system got this bad, likely because a lot of legislative leaders have overseen its decline.

There are a lot of reasons for this fiasco. Two of the biggest are poor investments and an unreasonably high assumed rate of return.

With terms like “unfunded liability,” “assumed rate of return,” and “amortization period” thrown around as if they were common parlance, it’s easy to tune out what happened. So let’s try this: Think of the pension system as your house.

Your house is an investment (like the pension system) that requires maintenance (paying the salaries of those who run the system) that can increase in value (pension system makes money) or decrease in value (pension system loses money).

Our legislators encouraged risky investments, which lost a lot of money. At the same time, members of the Retirement System Investment Commission, the agency that runs the state’s pension plan, received $1.4 million in bonuses in one year alone. Incredibly, this practice of awarding bonuses for losing money only stopped in 2013.

It’s as though the contractor you hired to add a bedroom and a bathroom not only didn’t perform the work, but burned half your house down. Clearly you would not be paying him for his work. You might take him to court. You certainly wouldn’t give him a bonus. That would just encourage him to burn the other half down. Yet they kept doing it, year after year.

That’s a bit more colorful than I would put it.

This is from Loftis, but back in 2013:

S.C. Treasurer Curtis Loftis has a $175 million point he’d like to make about the Palmetto State’s pension fund

…..

What is it? The S.C. Retirement System Investment Commission (SCRSIC) – which manages this fund – is continuing to produce sub-par returns for retirees compared with other government pension funds. Even as its managers tout “big gains …”

“Our fund performs in the bottom third compared with our peers,” Loftis noted this week. “That low performance is costing us big money. By being below average, South Carolina is leaving $175 million on the investment table.”

The pension fund posted a 12.4 percent gain in 2012 – basically recovering its losses from the previous year. But as Loftis points out the fund is still trailing both the broader market as well as other pension funds – which he attributes to its excessive fees and disproportionate reliance on “alternative investments.”

Yes, there are asset problems, as I’ve mentioned in previous points. But the funding approach is extremely problematic as well.

There’s plenty of blame to go around.

The asset side has bad shenanigans, but also there are shenanigans on the funding side.

This is going to be a very painful hole to try to climb out of.

Related Posts

Pennsylvania Pensions: Nibbling at the Edges

Priorities for Pension Funds: Climate Change or Solvency?

Calpers Craziness: A Performance Review... and an Investigation?